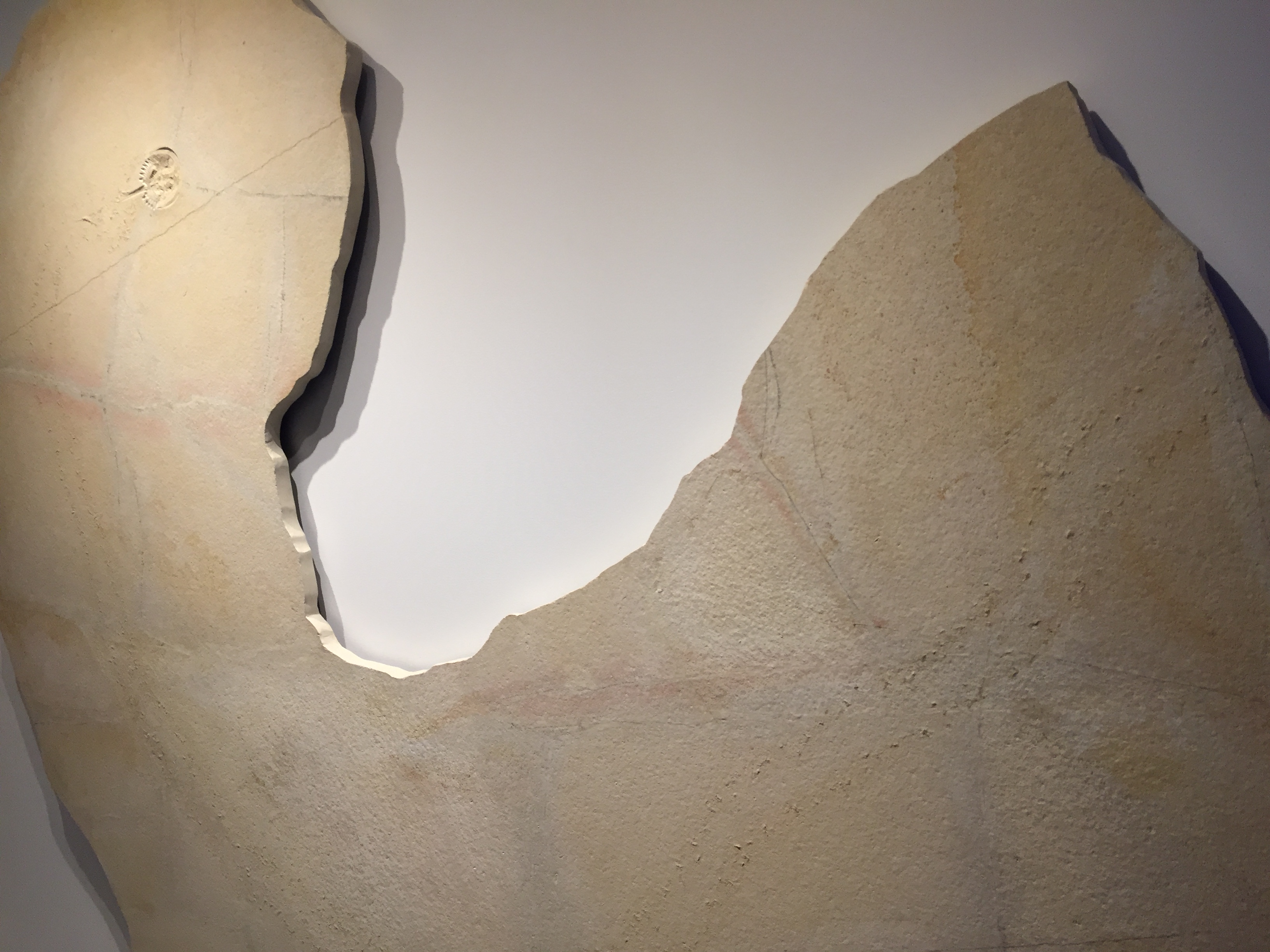

Horseshoe crab death track. Mesolimulus walchi. Solnhofen, Germany.

When people walk through our permanent exhibit halls, sometimes they come upon an object that makes them think “what in the world are they doing?“. It can be two fossilized skeletons posed in an unusual arrangement, or an artifact with a strange ritual depicted on it. This article is the final entry in a weekly series entitled What In The World Are They Doing? to be published on our blog. This week we are focusing on a tiny little creature that is stopping everyone in their tracks.

In our Morian Hall of Paleontology, there are plenty of dinosaurs that awe and inspire adults and children alike. Jaws drop, conversations stop and all gaze in wonder at the mighty skeletons dominating our hall. But there is one fossil that stops visitors in their tracks for a completely different reason. It is the fossil of a horseshoe crab in our Jurassic Oceans sections. “So what?”you may ask, “those animals are tiny, and on top of that they aren’t even extinct”. And it’s a good point. Although horseshoe crabs are pretty remarkable animals, you can see living ones to day. So what’s the draw? Well it isn’t the horseshoe crab itself, but what it is doing. Or rather, what it was doing right before it died. Preserved in the rock are hundreds of tiny footprints belonging to the fossilized creature. Museum patrons can actually see the path this animal walked just before its demise!

Detailed view of horseshoe crab and tracks

That brings us to the big question: what in the world was it doing? This fossil was found in an area of Germany world-famous for the fantastically well preserved fossils found there: Solnhofen. During the Late Jurassic period, around 161- 145 million years ago, this area of Germany lay on the coast of the Tethys Sea. This area of the coast was dotted with many little islands and its shallow, warm waters were home to coral reefs. In some cases these formations would cut lagoons off from the open sea and the water would become super salty, toxic to most living organisms. Some of these lagoons may have even been anoxic in deeper depressions.

Ancient Coelacanth, Holophagus sp. Upper Jurassic. Painten, Germany.

This is great for paleontologists because when animals died and their bodies sank to the floor of these lagoons there were few organisms living there to scavenge their flesh. This, combined with other unique environmental conditions like the super fine-grain, limey mud settling on the bottom of these lagoons , allowed soft tissues and bones to be preserved in qualities and quantities found almost nowhere else on earth. Solnhofen and surrounding areas are where Archaeopteryx was found, where our Coelocanth, our Rhamphoranchus and our little horseshoe crab were found.

Marine Reptile, Pleurosaurus goldfussi. Upper Jurassic. Painten, Germany

In the case of our horseshoe crab, the end was not as peaceful as sinking slowly to the bottom of a placid lagoon. Because the water was toxic to living organisms, sea animals that were washed, or wandered themselves, into these lagoons could not survive long. It is likely that this little horseshoe crab took a one-way ticket to no man’s land. It’s possible that the arching path the footprints take show the animal trying to return to good water, to go back to safety. It’s quite a thing to see: an animal’s last few moments of life preserved in rock.

Ancient Ray, Spathobatix sp. Upper Jurassic. Eichstatt, Germany.