After 90 days working at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, here’s the verdict:

I love it here!

Through research required to compose and edit posts for this blog, I have learned about voracious snails, shark extinction, dinosaur match-ups, efforts to clean up ocean plastic pollution, Houston’s flooding cycle, a mysterious society in south China, and the inspiration for the design of costumes for Star Wars.

Look at the size of that T. rex! My love for the Houston Museum of Natural Science began with an affinity for dinosaurs.

I’ve learned about many, many other things, as well, and I could feasibly list them all here (this is a blog, after all, and electrons aren’t lazy; they’ll happily burden themselves with whatever information you require of them), but the point of this blog is to excite our readers into visiting the museum, not bore them with lists.

Coming to the museum is a grand adventure, and it’s my privilege to be here every day, poking through our collection and peering into the the crevices of history, finding the holes in what humanity knows about itself and speculating about the answer. That’s what science is all about, after all. Learning more about what you already know. Discovering that you’ve got much more left to discover.

As a writer, I identify with the oldest forms of written language, like this tablet of heiroglyphs. You can even find a replica of the Rosetta Stone in our collection!

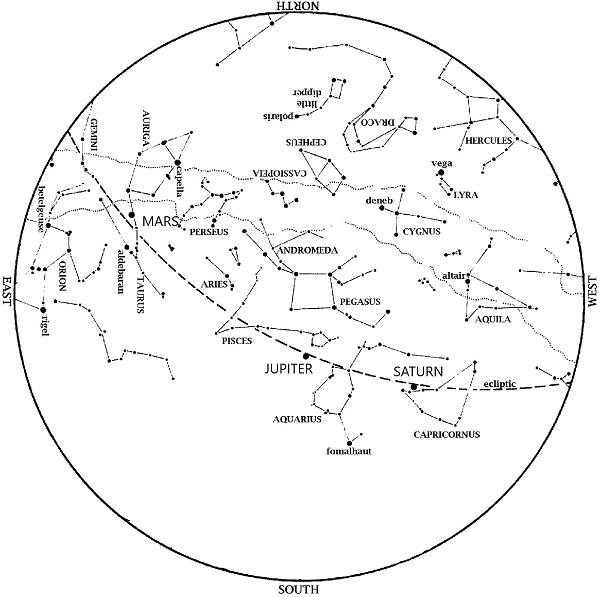

When I took this job, I was a fan of dinosaurs and Earth science. I could explain the basic process of how a star is born and how the different classes of rock are formed. Igneous, metamorphic, sedimentary. Now, I can tell you which dinosaurs lived in what era and the methods paleontologists use to unearth a fossilized skeleton. I know that a deep-space telescope owes its clarity to a mirror rather than a lens, and I can identify rhodochrosite (a beautiful word as well as a fascinating mineral) in its many forms. And there are quite a few.

Rhodochrosite. My favorite mineral. Look at that deep ruby that appears to glow from within, and it takes many other shapes.

I have pitted the age of the Earth against the age of meteorites that have fallen through its atmosphere and have been humbled. The oldest things in our collection existed before our planet! How incredible to be that close to something that was flying around in space, on its own adventure across the cosmos, while Earth was still a ball of magma congealing in the vacuum of space.

Time is as infinite as the universe, and being in this museum every day reminds me of the utter ephemeralness of human life. It advises not to waste a moment, and to learn from the wisdom of rock about the things we will never touch. Time and space reduce humanity to a tiny thing, but not insignificant. Our species is small and weak, but we are intelligent and industrious. We have learned about things we don’t understand from the things we do. The answers are out there if you know where to look for them.

Everything turns to stone eventually, even this gorgeous fossilized coral.

I was a print journalist for three years, and I am studying to become a professional writer of fiction at Vermont College of Fine Arts. (Don’t worry. It’s a low-residency program. I’m not going anywhere.) I am a creator of records of the human experience, according to those two occupations, and in some ways I still feel that as the editor of this blog, but there is a difference.

Here, rather than individual histories — the story of one person or of a family or of a hero and a villain — I’m recording our collective experience, our history as a significant species that participates, for better or worse, in forming the shape of this world. We were born, we taught ourselves to use tools, we erected great civilizations, we fought against one another, we died, those civilizations fell. We have traced our past through fossils and layers of rock and ice, we have tested the world around us, and we have made up our minds about where we fit into the mix.

We are a fascinating and beautiful people, and through science, we can discover our stories buried in the ground, often just beneath our feet. To me, this is the real mission of our museum. To tell the story of Earth, yes, but to tell it in terms of humanity. In the Cullen Hall of Gems and Minerals, we wonder what makes certain minerals precious to us when they’re all spectacular. In the Morian Hall of Paleontology, we trace the fossil record back in time and wonder how things were and could have been had dinosaurs not gone extinct. In the Cockrell Butterfly Center, we connect with the little lives of insects, compare them to our own, and fall in love with our ecosystem all over again. In the Weiss Energy Hall, we learn how life and death create the fossil fuels that now power our society. We find both ingenuity and folly in the values of old civilizations in the Hall of Ancient Egypt and the John P. McGovern Hall of the Americas.

These chrysalises, a powerful symbol of personal growth and change, teach a lesson in natural cycles and big beauty in tiny places.

I have often wondered how we justify placing a collection of anthropological and archaeological artifacts under the heading “natural science.” Why don’t we consider our institution more representative of “natural history?” In my first 90 days, I think I’ve found the answer. It’s not just about the story of humanity; it’s about the story of the science we have used to learn what we know.

The Houston Museum of Natural Science, including the Cockrell Butterfly Center, is truly one of a kind.

Our goal at HMNS is to inform and educate. To challenge your assumptions with evidence and bring the worlds and minds of scientists to students and the general public. It’s a grand endeavor, one that can enrich our society and improve it if we pay attention.

A ticket to the museum isn’t just a tour through marvels, it’s a glance in pieces at the story of becoming human. After 90 days here, by sifting through the past, I feel more involved in the creation of our future than I have ever been.

And that feels pretty great.