When I was super young, say around five or so, I remember playing in the bath tub with my plastic toys. Some were super heroes like He-Man or Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, others were monster trucks and die-cast matchbox cars by Mattel, but most were dinosaurs.

This might be TMI, this story about the kid in the bath tub with bubbles on his head, ramming plastic characters into one another and dreaming up their backstories, the bellows of challenge they traded, and the choreography of their battles, but I know there are other adult children out there with similar memories.

During this epoch in the evolution of me, I distinctly recall pitting Tyrannosaurus rex against Stegosaurus, which, as I’ve discovered in later life, was completely wrong, as was most of what I thought around five years old, but you know, who can blame a five-year-old for muddling up the fossil record?

T. rex is one of the most famous dinosaurs in history, easily identified by its massive, heavy skull, long steak-knife teeth, powerful back legs and tail, and ridiculous vestigial arms, but due to her status as dinosaur royalty, the length of her reign and her identity is as often confused by adults as it is by naive five-year-olds. The T. rex lived for two million years in the Late Cretaceous, never in the Jurassic, as her appearance in Jurassic Park might suggest, but we can forgive this fiction for its oversight. (After all, InGen, the engineering firm responsible for cloning extinct dinosaurs in the movie, infamously mismatched animals from different eras within the same park.) And she wasn’t the only two-legged carnivore.

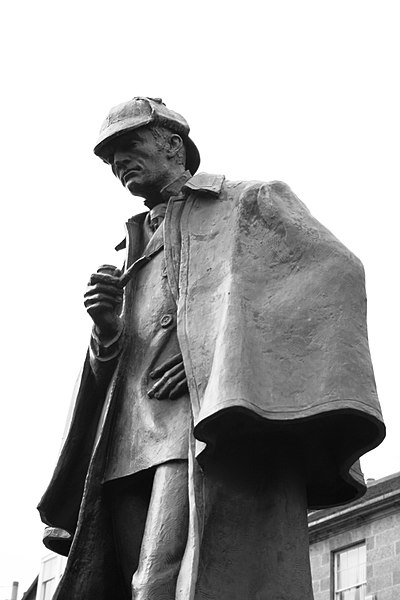

In a dramatic representation, Stegosaurus and Allosaurus duke it out in the Jurassic. Morian Hall.

In the time of Stegosaurus, between 155 and 150 million years ago (the real Jurassic), the apex predator was the Allosaurus. Smaller than the T. rex, but with more capable arms with three fingers ending in talons, this baddie no doubt picked battles with Stegosaurus, putting its life on the line for a meal. With its polygonal plates down its back, viciously spiked tail, flexible spine and toes that allowed it to rear up, Stegosaurus could give Allosaurus a true walloping.

Forget about jaws and claws. One solid hit from the bone spikes could deeply puncture the neck or torso of any shady Allosaurus looking for a bite, and its plates would protect its spine from being severed by teeth until it could land a blow. It isn’t difficult to imagine eyes gouged and jugulars perforated, many Allosauruses bleeding out after botched predatory encounters with Stegosaurus. There were certainly easier things for Allosaurus to eat, but few battles with other species could match the gladiatorial epicness of this match-up, at least not in this era.

Even as an herbivore, Stegosaurus would have made a formidable opponent against Allosaurus in the Jurassic, using a spiked tail and bone plates along its spine as defenses.

Fast forward 90 million years to the Late Cretaceous, the reign of the “tyrant lizard.” Tyrannosaurs roamed North America and Asia, preying on a variety of other famous megafauna like Triceratops, Ankylosaurus, and duck-billed hadrosaurs including Edmontosaurus, Brachylophosaurus, and Parasaurolophus. There’s no way T. rex even knew Stegosaurus was a thing. More time passed between these two than between dinosaurs and Homo sapiens.

As the largest predator of the Late Cretaceous, the T. rex is one of the fossil record’s most iconic species.

Nor was the T. rex the only one of her kind; she was just the largest, hence the name, “king of tyrants.” Among her smaller contemporaries, Tarbosaurus, Albertosaurus, Daspletosaurus, and Gorgosaurus, she was the Queen B, big and bad, in spite of the competition. She had excellent vision, a sense of smell that could detect prey from miles away, and decent hearing, though high-pitched sounds would have been lost to her. Food wouldn’t have been difficult for the T. rex to find, but that food really, really didn’t want to be eaten.

T. rex couldn’t have fought Stegosaurus, but it preyed upon Triceratops, another iconic species that lived in the same time period.

There’s no more famous match-up than Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops. With two long horns and a bony frill like a samurai helmet to guard its neck, as long as the trike met the T. rex head-on, there was no contest. But if Triceratops charged and missed the mark, the tyrant’s big jaws could take out its backbone in a single bite, neutralizing the threat of horns. Recent discoveries of casts of Triceratops‘s hide reveals nodules that might have housed quills, making even a bite to its back a dangerous one if T. rex ever got around the impenetrable helmet. You can imagine this battle yourself in the Morian Hall of Paleontology, where Lane the Triceratops takes a defensive position under an aggressor T. rex.

T. rex preyed upon Denversaurus and its famous cousin, Ankylosaurus, but both would have made a difficult meal, protected by bony armor.

Against Ankylosaurus and its cousin Denversaurus, also on display in Morian Hall, tyrannosaurs likely had a more difficult time. Both Ankylosaurus and Denversaurus developed the adaptation of a wide, low body and armored plating, making access to its soft underbelly impossible for tyrannosaurs unless kicked onto its back, but Ankylosaurus had another advantage. The tip of its tail bore a mace-like club that, like Stegosaurus’s spiked tail, could maim the jaws of predators that didn’t pay enough heed. One swing from this heavy weapon could break open a T. rex‘s face, cripple its legs, or shatter its ribs, and with arms too small to defend itself, dodging seems the only tactic at her disposal against this tank of a creature. An encounter with an Ankylosaurus could mean either a meal or certain death, depending on the T. rex‘s experience hunting.

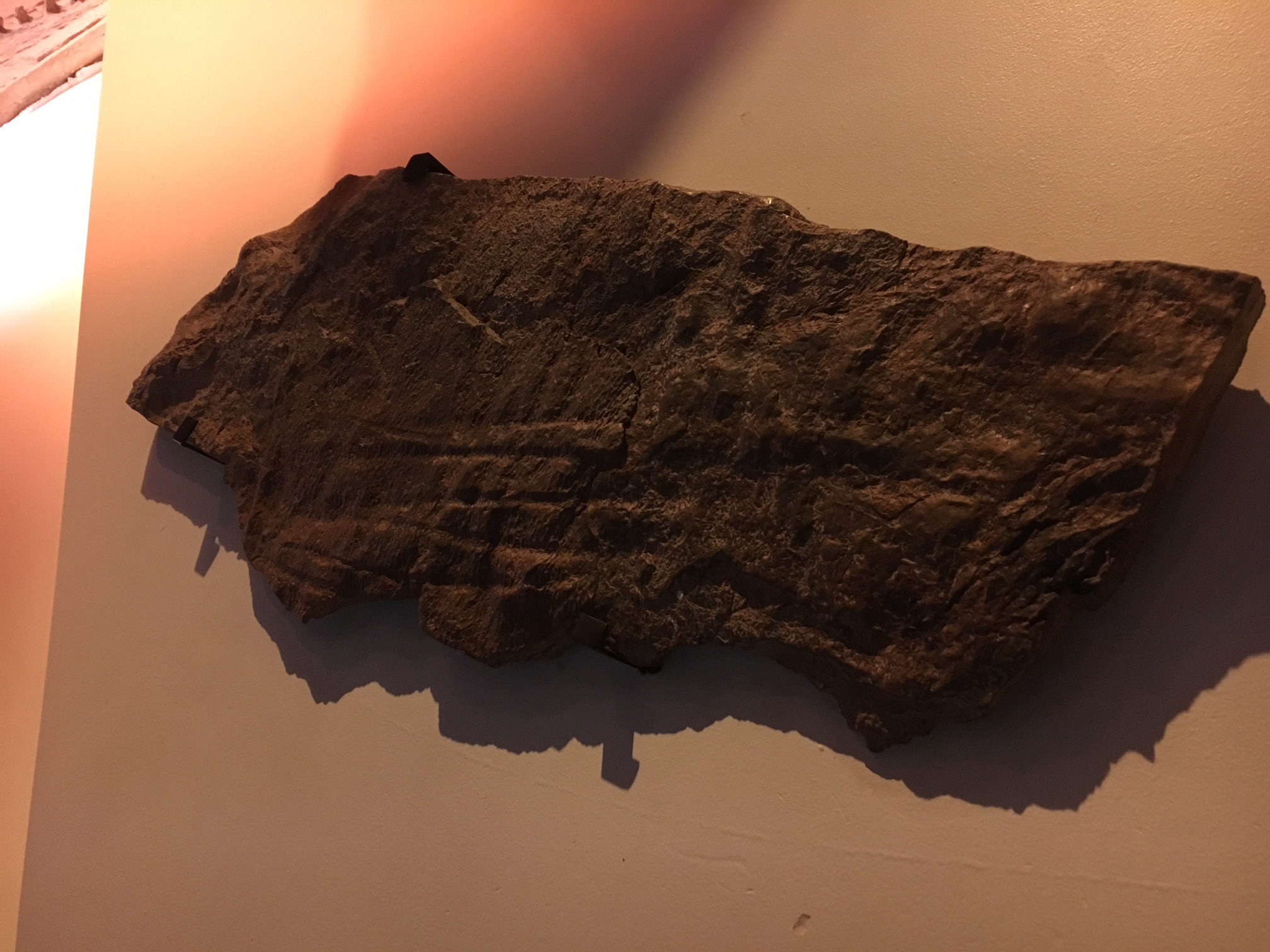

Armor plating on the back of Denversaurus would have protected against a bite from the T. rex and other tyrannosaurs of the Late Cretaceous, but if flipped over, its soft underbelly would be exposed.

A more easy meal for any tyrannosaur would have been Edmontosaurus and other duck-billed dinosaurs. These hadrosaurs had few defenses. No armor plating, no spikes, no claws, no wings, no sharp teeth. But it’s possible they had a different advantage, though it’s tough to deduce through fossils alone. Hollow chambers in the skulls of many hadrosaurs suggest these creatures, like geese and other water fowl, had the power of sound at their disposal. A deafening bellow might have stopped a tyrannosaur in its tracks or sent it running in the other direction. T. rex isn’t known for its sensitive hearing, but as we all know, if the sound is loud enough, it can be excruciating. And T. rex had no fingers to put into her ears, nor could she reach them.

Edmontosaurus, a duckbilled hadrosaur and cousin of Parasaurolophus, appears to have lacked natural defenses. However, the hollows in its skull suggest it could have protected itself with deafening bellows like giant geese.

Understanding these species as they once were, interacting with one another, is more than bath tub child’s play for paleontologists; it’s a career and a discipline. It’s in the Greek roots of the word “paleontology,” the study of being and beings in the ancient world. The study of what life on Earth might have looked like eons ago. The work of these scientists is more like philosophy than fiction, but building careful theories via the fossil record and considering every angle does require a measure of imagination.

An artist’s representation depicts Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus rex in an age-old feud set in the lush swamps of the Late Cretaceous, an imagined scene deduced from evidence in the fossil record. Morian Hall.

I suppose, apart from the spikes and teeth and horns and claws and body armor and all the other things that make these terrible lizards seem like something out of science fiction, or monsters invented by a puppeteer, it’s the daydreaming paleontology requires that holds my attention. To understand their world, you must build it in your mind.