Today on Beyond Bones I’m going to tell you a story of two Victorian Academics who spent the majority of their careers going to absolutely ridiculous lengths to out-science each other in a decades long clash of brains and ego.

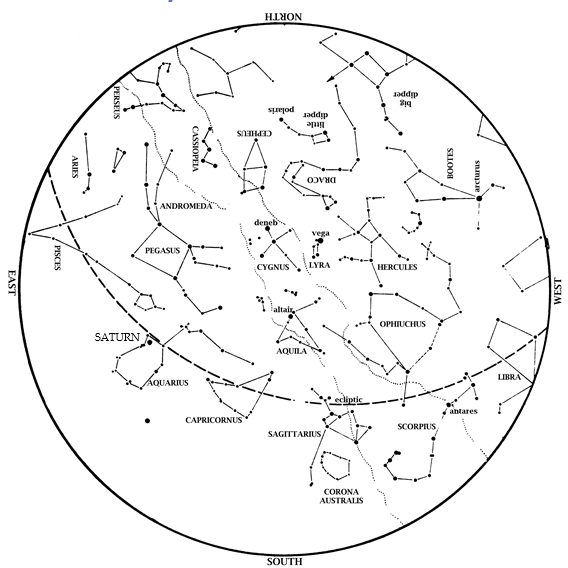

The feud has come to be called the “Bone Wars” by Paleontologists and its effects can still be felt in paleo-circles today.

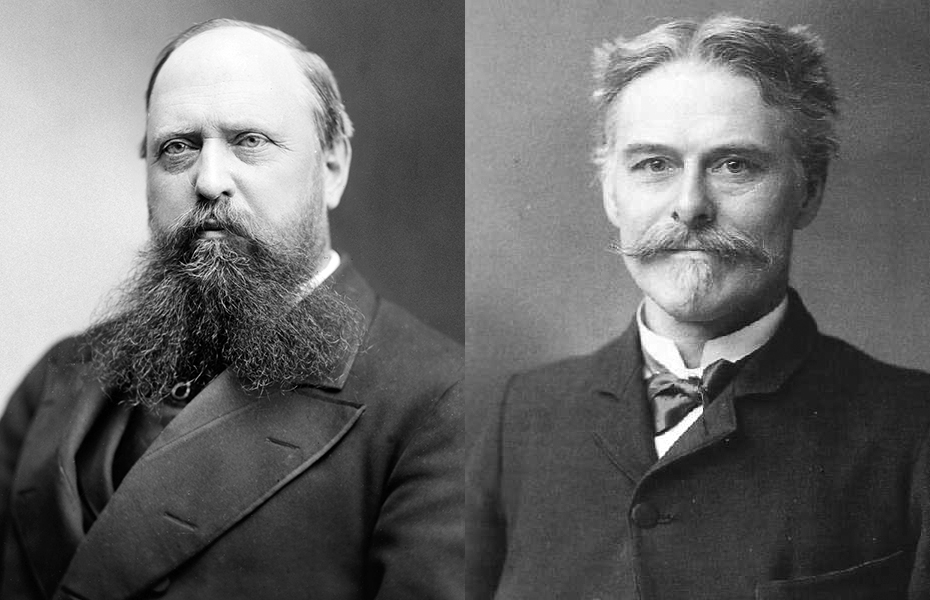

The rivalry between Othniel Charles Marsh (left) and Edward Drinker Cope (right) sparked the Bone Wars. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The protagonists of this story are two paleontologists, Othniel Charles Marsh (1831-1899) and Edward Drinker Cope (1840-1897). They are also the story’s antagonists, each being their own worst enemy. Not only do their names sound like characters in a Jules Verne novel, their actions also resemble something out of Victorian era fiction. But I’m getting ahead of myself. First, let’s set the story up.

As with all great rivalries, the relationship between Cope and Marsh began rather amicably. The two met while studying paleontology in Germany in 1864. Marsh was a poor country boy from New York who was studying abroad thanks to the patronage of a rich uncle. Cope had been brought up in a wealthy landowning family and he may have been draft dodging the Civil War in Germany. Both had brilliant minds and a passion for the natural sciences.

Despite both budding scientists being notoriously difficult to work with, they somehow formed a friendship. When the two returned to the United States and took positions at esteemed universities, they even named newly discovered ancient species after each other. Little could either of them have predicted the epic clash that would soon consume their lives.

The clash began in 1868 when Cope gave Marsh a tour of a fossil quarry in Haddonfield, New Jersey. Behind Cope’s back, Marsh made an agreement with the quarry owner to send any new fossil discoveries to his offices at Yale.

SIDE NOTE: Marsh had convinced his rich uncle, millionaire George Peabody, to donate $150,000 to Yale to establish the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Marsh served as a trustee and one of the museum’s curators. I wish I had a rich uncle.

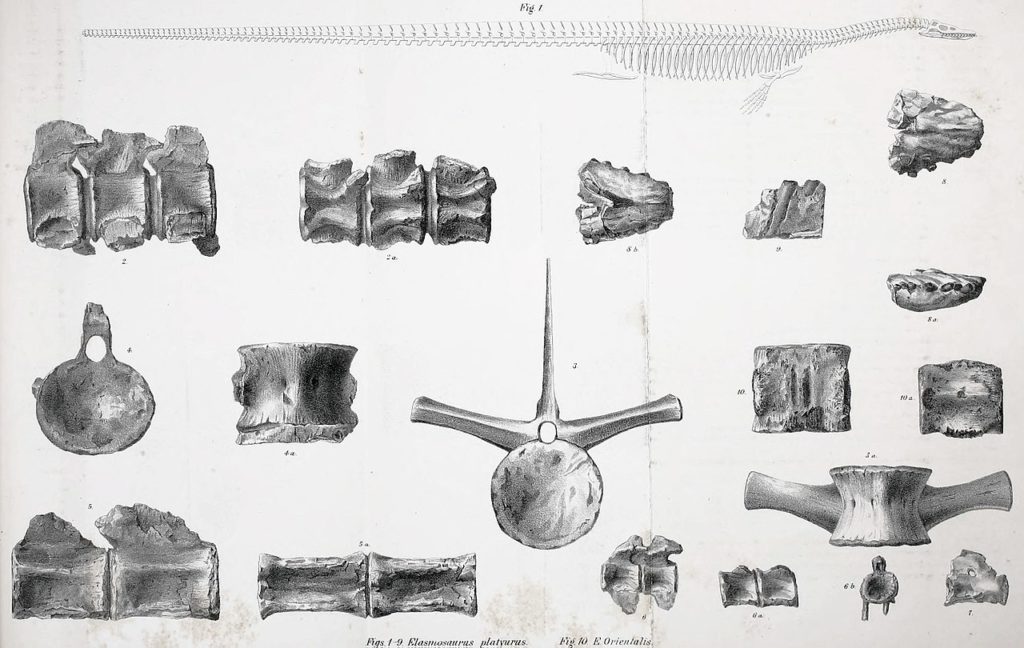

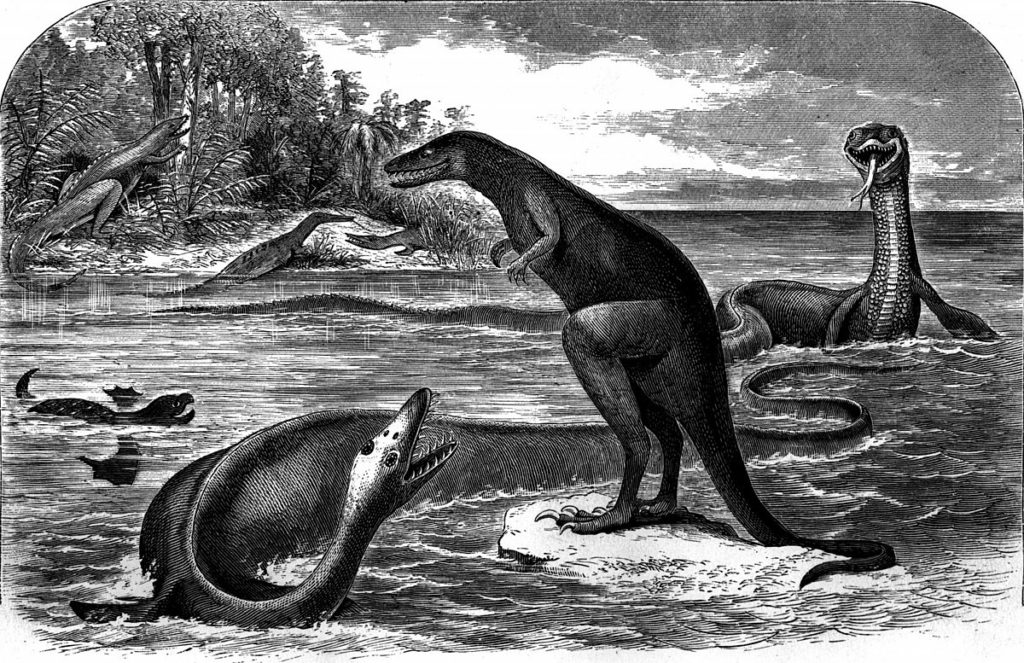

Cope was of course perturbed when he discovered this betrayal, but soldiered on and tried to focus on his work and forget about it. The same year he published an article on a newly discovered dinosaur relative, Elasmosaurus platyurus . In his reconstruction of the creature’s skeleton, Cope made a pretty hilarious mistake. He put together the body of the skeleton perfectly, but he accidentally put the skull at the end of the tail instead of at the end of the neck. He put the head on the wrong end!

Cope’s 1869 reconstruction of Elasmosaurus above, with head on the wrong end and no hind-limbs, and holotype elements of E. platyurus (1-9) and E. orientalis (10) below. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

When this unfortunate mistake was pointed out by Marsh, an embarrassed Cope attempted to purchase every issue of the American Philosophical Society journal that featured his erroneous article. This was the end of end of any pretense of amicability between the two. To quote Marsh: “when I informed professor Cope of [his error], his wounded vanity received a shock from which it has never recovered, and he has since been my bitter enemy”.

Melodramatic much?

This betrayal sparked a 30 year race between these two eminent intellectuals to see who could name the most new dinosaur species. And when I say “race” I’m not being metaphorical. With the settlement of the western territories, fossils were being unearthed at an unprecedented rate by farmers, railroad workers and small town school teachers. As soon as word about a fossil find reached their ears, Cope and Marsh would rush by train to try to claim the site before the other.

Marsh (back row and center), surrounded by armed assistants for his 1872 expedition. Marsh spent little time in the field himself, generally delegating these tasks to his agents. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

A good example of this is the Morrison incident. In 1877 a schoolteacher named Arthur lakes discovered large fossils near the town of Morrison, Colorado. Lakes sent some of the bones to Marsh and some to Cope. Marsh quickly published the find, and when he found out that Lakes had sent some of the fossils to Cope he paid the school teacher $100 for ALL of the fossils he discovered. Lakes sent a letter to Cope asking him to forward the the bones he had sent to Marsh.

Soon after, Cope received a letter from a man named O.W. Lucas of Cañon City, Colorado. Cope soon set up a fossil quarry there. Upon hearing about Cope’s discovery, Marsh sent some of his men to set up another quarry near by and even went as far as to have some of his agents to bribe Lucas to join the dark side with them. Lucky for Cope, Lucas remained loyal to his professor.

Arthur Lakes’s sketch of expedition members in Como Bluff. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Meanwhile, Marsh received a letter from railroad workers in Wyoming of yet another find at Como Bluff. He quickly sent some of his men to investigate. Now it was Cope’s turn to be sneaky. Cope sent some of his own men to the area and set up his own quarry. Como Bluff is where tensions between the two reached their climax. At this random little spot in the middle of the wildest part of the frontier, the most ridiculous and petty war fought in human history was waged.

The conflict featured all the hallmarks of a good war, spying, sabotage and explosions. Each side would would send spies to check out the other’s quarry. The bitter conflict consumed yet another friendship when the pair who originally discovered fossils at Como Bluff, William Reed and William Carlin, were each drafted into opposing sides of the struggle. Carlin and Reed brought new levels of pettiness to the competition, sending spies to the other’s camps. At one point, Carlin locked Reed out of the local train station, hoping that Reed wouldn’t be able to load his crates full of fossils onto the east bound Train in time for departure. At another point, the opposing teams literally threw rocks at each other. They would also dynamite quarries that they were finished with in order to destroy any fossils they might have missed to make sure the other side didn’t get to them. You know, like any great scientist would do.

Marsh and Lakota Chief Red Cloud in New Haven, Connecticut, c. 1880. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Marsh lead the race the majority of the time due to his personal wealth (inherited from his uncle who died in 1869) and political connections. He spent extravagant amounts of Yale’s money (in one case $15,000, which is $200,000 in today’s money) on expeditions to the West with his students, opening up numerous fossil quarries. He even made an agreement with Lakota Chief Red Cloud in which, in return for rights to prospect on their land, he agreed to lobby Congress for better treatment of Native Americans and defense of the Sovereignty of their land.

To Marsh’s credit, he actually did go before Congress to argue the issue. This was in an age when prospectors of a different sort were violating the sovereignty of Indian territory without a second thought. Anybody hear of Deadwood?

After the mid-1870’s Marsh rarely went into the field, sending his agents to dig and prospect instead. Meanwhile, Cope was hemorrhaging money funding his various plaeo projects, most of which he personally directed. In an effort to win back some of his fortune he invested in a silver mine in New Mexico that ended up going bust.

Illustration plate to Cope’s 1870 description of several reptiles, including an improperly reconstructed Elasmosaurus (foreground). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In the end, both paleontologists ended up dying broke and alone, Marsh never married and Cope eventually separated from his wife. The pair left a dubious legacy in the history of paleontology. On one hand, they discovered so many new species of dinosaurs and other ancient creatures, including Allosaurus, Stegosaurus, Diplodocus, Pterodactyl, Triceratops and many others. On the other hand, their antics pushed other paleontologists out of the field and generally hurt the credibility of their field, especially after a series of newspaper articles brought their feud to public attention in the 1880’s.

Another negative effect of their competition was the numerous redundant species they concocted. In their haste to out-publish each other they didn’t bother to fact check. Many of the “new” species they named had actually already been discovered by someone else and given another name. For a long period there were many dinosaurs with two or even three scientific names. To this day paleontologists are still whittling down the official number of dinosaurs species by cutting out Cope’s and Marsh’s redundant names.

SIDE NOTE: Once again I have to give Marsh credit here; although he did make mistakes, in general his theories and classifications were pretty solid. Cope’s, on the other hand, were often fraught with inaccuracies. Also, Marsh was a supporter of Darwin’s theory of natural selection, while Cope still adhered to Lamarckian evolutionary theory even as late as the 19th century.

Good or bad, these guys undoubtedly left their mark on the field of paleontology. Every paleontologist knows about the “Bone Wars”, and the subject is referred to often in discussions of the history of paleontology. The way people refer to it its’s almost as if it was a real war.

Some of the fruits of their labor can be seen in our own Hall of Paleontology. The Hall is dominated by our massive Diplodocus skeleton, which we affectionately refer two as “Dipsy”. Hiding in a corner behind Dipsy is the diminutive skeleton of Othnielosaurus, named after Othniel Charles Marsh. The fox-sized dinosaurs was originally discovered Marsh’s men and named by Marsh “Laosaurus consors”. Later, the species was reclassified and renamed “Othnielosaurus” in honor of its discoverer. HMNS’ dig sight in North Texas, where many of the Permian-era fossils displayed on our exhibit were collected, was originally explored by Cope. So, all in all, we have a few reasons to be thankful that these guys existed.