“Attention all Dino-Nerds! Put Your Anatomical Expertise to Work. Prestigious Careers Await in the Field of Gastroenterology.*”

Where the guts fit in a T. rex. The pubic bone (yellow) sticks down and won’t let the intestines expand behind the hip socket.

Often, I get approached by parents who fret over their dino-fixated kid. “You gotta help us, Doc. All she wants to do is read about fossils. Will she ever find a respectable career in the real world?”

I can reassure Mom and Dad that studying dino anatomy can lead to well-paid and honorable occupations — for instance, as a professor of anatomy or a foot surgeon or a knee specialist. Or a gastroenterologist. Being a gut doctor is becoming especially attractive now because aging yuppies are suffering from decades of intestinal abuse from spicy nachos and a misplaced reliance on gluten-free pizza.

So, adults, encourage the children to delve deeply into the dinosaurian intestines. It’s fun. It’s educational. It might pay off — big time.

T. rex was a gut-less wonder

The first step toward a visceral understanding of dinos is to face the fact that T. rex was a gut-less wonder. Consider the rexian body cavity. The space available for guts is severely limited. That’s because the intestines must stop at the pubic bone, the big prong that points straight down from the hip socket. It’s inviolable anatomical law: No intestines can be behind the pubis!

In a rex, that means all the guts are in front of the hip socket and there just isn’t a lot of room here. You might argue that rexes were forced to be pure carnivores because they needed high protein food that could be digested with a minimum weight of gastric equipment.

(Vegan advice: A gentle admonition to all my vegan friends in Boulder, Colorado: High fiber plant food demands big, complicated gut compartments, a series of vats where the fodder is soaked and softened, worked upon by microbes that secrete the enzymes needed to break down fiber. That explains why Herefords and zebras, which are consummate digesters of grass, have naturally rotund tummies. Contrary to widespread myths, we humans, when we first evolved, were not adapted to high fiber, animal-free diets. When Australopithecus evolved into our genus Homo, the size of the gut shrank dramatically. So we had to specialize in protein-rich food, such as eggs, baby birds, grubs, turtles, bunnies and antelope carcasses scavenged from unwary saber-tooth tigers — plus, of course, nutritious fruits and nuts and tasty tubers excavated with digging sticks and roasted over the fire. Fire was domesticated at about the time our guts diminished in volume. Cooking releases food value otherwise unobtainable with our small-size intestines. Today, a modern human can indeed survive on a plant-based diet but you choose your veggies carefully. And cook ‘em.)

Chickens that don’t fall over

Now that we’ve learned the basic laws of gut size, we are ready to unlock the mystery of the balanced chicken. You’ll remember from the previous post that barnyard fowl have exquisite balance on just two legs, despite the lack of a heavy tail.

Here’s another fowl mystery: Chickens have formidable digestion. They can extract food value out of raw grains and plant fiber far better than we humans can. The secrets to balance and digestion are one in the same — the gut-wrenching development of the pubic bone. When an embryonic bird in its egg is just beginning to develop a pelvic skeleton, the pubis points down, sorta like an adult T. rex pubis does. But when the chick hatches, the pubis has rotated completely around so it points backward and the guts expand behind the thigh.

Brilliant! The pubic re-alignment has doubled the potential room for intestines. And all that new weight of intestines is behind the hips, and therefore, confers perfect balance without any sort of ponderous tail.

Pubic-wrenching is a splendid osteological trick. Some dinosaurs did exactly the same thing. Stroll past our fine duckbill skeletons. Fix your gaze on the pubic bone. It’s rotated backward, just like a four-ton version of the barnyard fowl.

The duckbills go even further in gut expansion than do most birds. The pubis and ischium (the other lower hip bones) are so extended toward the rear that the guts gain another yard or two of length and allow another couple of chambers for microbial action on the food. All those extra digestive vats would let the duckbill G.I. tract break down even the toughest, most fibrous vegetables.

Duckbills win the award for longest gut tract of any dinosaur. And, probably, had the least constipation problems.

There’s a word every dino-nerd learns in the first grade: “ornithischians”. The simple meaning is “dinos with bird-style hips,” and that denotes the many species, like duckbills, that have undergone gut-wrenching. Stegosaurs wrenched their pubes, as did Triceratops.

Make a game of it! Go through our Fossil Hall with the children seeing how many different skeletons show the backwardly-bent pubes. Make the whole family pubo-literate!

Before and after gut-wrenching experience: Top duckbill dinosaur shows how intestines would be limited if the animal had the primitive, vertical pubis. Bottom duckbill shows the real bent-back pubis and ischium.

When I skulk around our tour guides as they talk to school groups, my rib cage swells with pride. Our docents are the best! So I want to add an advanced bit of pubic-lore here. Stegosaurs and many other gut-wrenched herbivores do something tricky, pubis-wise.

After they evolved the backward-pointing pubis, these dinosaurs grew new pubic prongs — one on each side of the rib cage — that pointed forward and outward. This new set of prongs didn’t change the gut layout at all. The new prong lies outside the body cavity. The guts lay between the left and right new prongs.

What good did the new prong do? A stout muscle probably attached to it and ran back to the thigh to help swing the hind leg forward. If your child is considering med school, tell her that this muscle is what we call in humans the “psoas.”

Colorado State dino, Stegosaurus, showing the new prong of the pubis that points forward. Don’t confuse it with the true pubis!

And now, the ultimate Darwinian inquiry into gut-wrenching, the question that earns me sour stares from all my creationist relatives (37 full cousins on one side, 97% creationists)…

Here’s the query: When did pubic-twisting happen in the evolution of birds?

The chicken diagram I used earlier works pretty good for all modern day birds — every single one of the 10,000 species. From hummingbirds to ostriches, today’s avian species have the strongly wrenched pubic shaft and the attendant elongation of all things intestinal. No modern bird has the vertical pubis and short gut of a T. rex.

Diagram of Archaeopteryx from Heilmann’s 1926 book “Origin of Birds”, modified by me in 1958. Heilmann explained the mix of bird and pre-bird features.

Archaeopteryx surprises

When first discovered in the 1860s, the Late Jurassic Archaeopteryx was an evolutionary celebrity, a missing link combining perfectly formed avian designs with archaic dinosaurian features. The first “Archie” skeleton excavated was jumbled but it certainly looked like the long, thin pubic bone was bent back in standard bird configuration. “Archie” also possessed another definitive bird device — the lagoonal, limestone-preserved imprints of fully-formed flight feathers.

Some dino characteristics were retained too: sharp little teeth, curved claws on the fingers, separate bones in the wrist (modern birds fuse up the individual bony units), and a long bony tail. The Archie was dubbed “Ur-Vogel” in German, an event which solidified the critter’s place in nature.

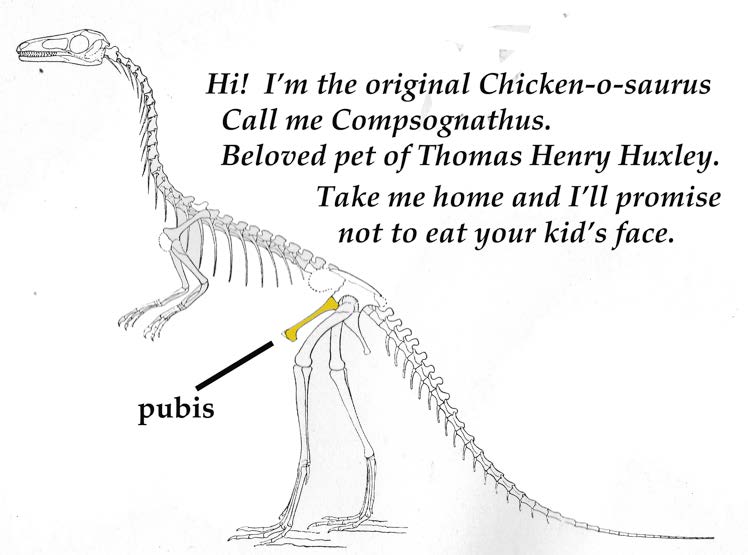

“Proof that creationism is wrong and Darwin is right!” shouted many an agnostic in 1868. In fact, the chap who coined the term “agnostic,” Thomas Henry Huxley, led the charge in proclaiming birds as descendants of wee dinos. Huxley’s favorite dinosaurian was Compsognathus, the original “Chicken-Dino,” a Late Jurassic carnivore extracted from the very same lagoonal rock that produced Archaeopteryx.

The Compy skeleton was cute as a button — so small that Huxley could imagine it perched on his shoulder during debates about Darwinism. When I began reading dinosaur books in the 1950s, the Compy was still the tweensiest dino known and several kids’ stories had a pet Compy following a second grader to school.

That image was just too cutesy-pootsy, too Disney, and the Compsognathus needed a makeover to give the species gravitas. The Jurassic Park franchise of the 1980s did just that. In the first Jurassic Park book, Compys are turd-eating pack-hunters that would jump up into a crib in a children’s hospital to bite off the kid’s nose and cheeks and rest of the face. That scene definitely stripped away the excess cutesy.

In the movie Jurassic Park, the Compys were upgraded to frilled little monsters that spat narcotizing pea-soup in the face of characters before biting off their noses, cheeks and rest of their faces. That scene ripped away the excess pootsy.

Movie villains can seem especially evil when they begin as pint-sized plush toys and then metamorphose into killers. Remember Gremlins and Chucky? (Maybe the writers of Jurassic Park scripts were trying to do to Compys what Miley Cyrus did for herself — take an adorable little star and remake the image so it seems more adult and more formidable. I believe that, when you go slow-motion through the Jurassic Park movie, you can see some of the Compys twerking.)

(Be advised: Jurassic Park books and film mix and match parts from three different dinos: (1) The true Compsognathus, beloved of agnostics; (2) The enigmatic pro-compsognathids known only from incomplete Triassic specimens; and (3) The distant compy cousin, the hefty 20-footer, Dilophosaurus, from the Early Jurassic. None were poisonous. None could spit. But recent discoveries from China reveal a raptor with teeth grooved like a gila monster’s — that means poison glands dripped venom down the grooves into wounds. Cool.)

In all three real dinos that inspired the Jurassic Park Compys, the pubis pointed downward and forward, the primitive configuration for carnivorous dinos and retained in our Texas Coelophysis. No gut expansion here.

In all three real dinos that inspired the Jurassic Park Compys, the pubis pointed downward and forward, the primitive configuration for carnivorous dinos and retained in our Texas Coelophysis. No gut expansion here.

Bambiraptor, a little raptor-type dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous. Diagram done for Dr. David Burnham and me when Bambiraptor was named. Note that the pubis is bent back just a bit.

In the 1970s, Yale’s John Ostrom rediscovered Huxley’s insights. He used the recently discovered Deinonychus and its kin to prove that raptor-type dinos had hands, feet and a tail nearly identical to what Archaeopteryx possessed. But raptors still had primitive pubic bones that were bent back just a little bit. See the raptor-pubes for yourself in our “Julie-raptor” skeleton on display at HMNS or in the Bambiraptor skeleton in the lab (come by and take a look).

So, because of its superior pubic wrenching, Archaeopteryx was entitled to be hailed as more advanced than most raptors.

That made us all happy because we could make a nifty evolutionary scenario — an early raptor-like dino, a Jurassic version of Deinonychus, evolved into an Archaeopteryx-oid and then the Archie-oid evolved into a modern bird in the Early Cretaceous. Take that, my creationist-cousins!

(By the way, don’t let TV’s South Park mislead you; the plural of “pubis” is “pubes,” and it’s pronounced “pew-bays” and not “pewbs.”)

But then came the inevitable Oops Moment. That happens whenever we get too cocky.

Our friends at the Thermopolis Dinosaur Center in central Wyoming announced they had obtained a near perfect Archaeopteryx in 2006. I rushed up to ogle it, armed with a zillion photos of all the other Archie specimens. I stared at the pubes.

The new specimen and the other best specimens showed that the simple pelvic scenario was wrong. The real, undistorted Archaeopteryx pubis pointed straight down. No backward wrenching at all. In other words, Archies had no gut expansion whatever. The Ur-Vogel was no more advanced in this one key hip feature than an allosaur or a tyrannosaur.

A very accurate diagram of Archaeopteryx, drawn by the magisterial paleontologist Peter Wellnhofer, who is the all-time expert on Jurassic pterosaurs and birds. Note the disturbingly vertical pubis.

Dang, dang, double dang

In this one famous feature, the backward wrenching of the pubis, Archaeopteryx turns out to be less like a modern bird than Bambiraptor or Deinonychus. Gosh … nearly every ornithischian dinosaur has more advanced pubic positions than does an Archaeopteryx.

We should’ve known. Evolution hardly ever goes in a neat, straight line. The origin of birds didn’t come about as one undivided line of dinos that gets better and better, more and more like a chicken, from the Triassic through the Jurassic and then into the Cretaceous. Darwinian family trees are much more complicated and much more confusing — more like tangled blackberry bushes, full of short branches going off in all directions. There are side branches and side branches coming off the side branches.

Archaeopteryx itself couldn’t survive by being a mere ancestor; it had to fit into its local environment; it had to be adapted to its immediate surroundings. The short gut and un-wrenched pelvis worked fine. A cluster of raptor-like dinos, with minor variations in pubic slant, shared the basic Archaeopteryx blueprint — and they too thrived for millions of generations. Even in the latest part of the Cretaceous, un-wrenched guts with vertical pubes contributed to the success of little Bambiraptor type predators.

Finally, after the Cretaceous ended, all the raptor-type dinos and all the birds with vertical pubes were extinct. Now, in today’s habitats all over the world, no bird or bird-like animal operates with the un-wrenched gut. Why? Did the short gut prove inadequate somehow in the long run? Could be. But we must remember that short-gutted birds and raptor-like dinos had done very well since the Mid Jurassic to Late Cretaceous, and that’s a full 100 million years. It’s not totally true, the old adage, “No guts, no glory.”

* It’s traditional for paleontologists to teach anatomy to pre-meds. I did that for years: at Harvard, then at Johns Hopkins. Thomas Henry Huxley, who worked out relations between little dinos and birds in the 1860s, also taught courses in basic dissection. It’s even more socially acceptable to be a genuine medical doctor who also digs fossils.

True story, not a Seinfeld episode: When I visit my mom at the retirement home, she introduces me as “my son, Dr. Bakker.” All the octogenarian ladies lean forward smiling. Then, politely, they begin to ask specific questions about certain medical conditions. Mom whispers, “He’s not a real doctor…” and all the ladies lean back with a slight curl of disapproval in their smiles.

Nota bene: The new book Ten Thousand Birds, (Princeton University Press), is wicked good — best ever done on our feathered species. Beautifully written. Everyone should get a copy.