In Part I, we talked about the Cockrell Butterfly Center’s Little Coffee Tree That Could, and how we grow, harvest, and dry coffee beans. But even after all this work, the beans are still not ready to consume. So let’s talk about how we get the dried (parchment) coffee to a state that can be enjoyed by the masses!

Hulling

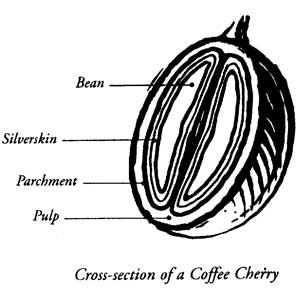

Once the beans have been prepared and dried, the parchment — a thin, brittle skin that completely covers the bean — must be broken and the green bean removed. This is typically done by a special machine that shakes the beans, and the vibrations knock the parchment off.

Unfortunately, we didn’t have access to any of these machines, so we went through this process by hand — and the entire Butterfly Center staff and volunteers have the calluses on their fingers to prove it (of course, hindsight is 20/20 and we could have probably used a rock polisher and saved ourselves some labor, but I’m sure even Juan Valdez went through some trial and error before he perfected his process!).

Roasting

Now being the traditionalist sort who orders a “large coffee” if I ever find myself in a Starbucks, seeing some of the advancements and new technology when it comes to roasting and brewing was a real eye opener.

Enter local roaster Matt Toomey of Boomtown Coffee in the Heights. Lucky for us, Boomtown had a roaster small enough to accommodate our single harvest, and Matt was happy to explain the process to us — the uninitiated roasters.

First, we weighed out the beans to be roasted and preheated the electric sample roaster. The temperature needs to be around 480 degrees Fahrenheit so that the beans can be heated to between 380 and 480 degrees, depending on the desired roast (as soon as you add in the beans, the temperature drops significantly). So, 380 degrees yields a light or cinnamon roast, while 480 degrees gives you a dark Spanish roast. The roaster we used can only hold about 1 pound at a time, however, the basic idea behind all roasters is the same: turn the beans continuously to ensure uniform roasting of the beans. The central drum spins the beans as they roast to achieve this uniformity.

FUN FACT: Experienced roasters know when the beans are ready — not by smell, but by sound. The coffee bean, much like popcorn, will pop or crack up to two times as it roasts. For our Blue Morpho Blend, we did a full roast, or specifically a “full city roast” — which means you pull the beans out at the beginning of the “second crack.”

After all this work, we finally have a bean that is ready to grind and brew. But wait what if it’s not any good? If we made any mistakes during the growing, fermentation or drying process it can give the beans a foul odor and taste; this is where “cupping” comes into play.

Cupping

Cupping is a method of taste testing coffee to determine the quality of the bean. You take a small cup, and observe the different aspects of the brew, like aroma, body, sweetness, acidity, flavor, and aftertaste. We did this using a Chemex brewing system, shown below, which is the opposite of a French Press. Where a French press leaves a lot of sediment in the coffee, the Chemex uses a very fine filter that creates a “cleaner” coffee.

Success! The Blue Morpho Blend passed the cupping with flying (or should I say fluttering) colors! We found it has an earthy, almost nutty aroma, with a flavor that has a hint of amaretto, and an amazing aftertaste!

Now a lucky few will get the chance taste it and tell us what they think at our Butterflies and Beans event on Jan. 18th. We’ll let you know what they say!