When we think of coffee, we normally assume that the best quality coffee comes from Java, Colombia, Ethiopia, or Kona. But maybe it’s time to add Houston to the list!

This year at the Houston Museum of Natural Science’s Cockrell Butterfly Center, we were fortunate to have a large enough crop on our coffee tree (Coffea arabica) to harvest, process and roast — which means we’ve got brews for you! This journey has given me a brand new respect for my daily cup of Joe.

Come along with me, and I’ll let you in on how to be one of the select few who gets to sample this exclusive Houston grown “Blue Morpho Blend” at Butterflies and Brew: HMNS’s first harvest.

Botany

Coffee comes from the plant Coffea arabica, a member of the family Rubiaceae which is native to Ethiopia, but now grown throughout the tropics. The plants make small trees, growing 10-15 ft. in height, with glossy, evergreen leaves. The small, white flowers smell like gardenia (a member of the same plant family). The flowers are typically self-pollinating and take between six and eight months to ripen into a red fruit called a “cherry,” each of which contains one to three coffee beans.

A typical coffee plant will take between three and six years from germinating until it begins to produce fruit. As it happens, our tree in the Butterfly Center is about four years old.

FUN FACT: Our tree was a surprise. It appeared as a seedling from a stray bean that fell off an older coffee plant that was taken out several years ago.

History

History

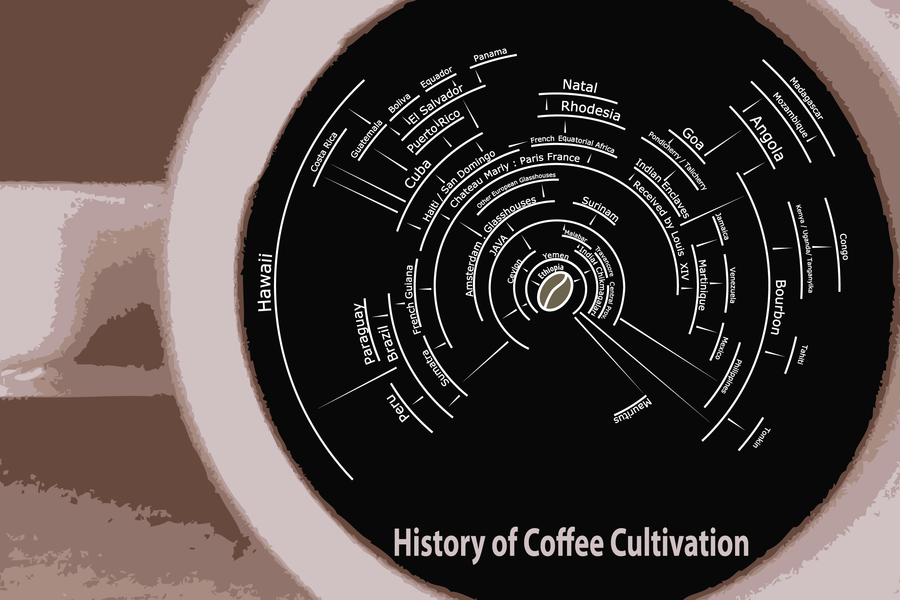

Although many legends surround coffee’s origin (all of them very interesting), the first official account of people using coffee for its stimulant properties can be traced back to the 15th century in the monasteries of Yemen. By the 16th century, coffee had made its way all over the Middle East, Turkey, Persia, and North Africa. From there it spread to Europe, Indonesia, and finally North and South America — and the rest, as they say, is history.

FUN FACT: Americans spend nearly 4 billion dollars per year importing coffee. A majority of Americans (63 percent or 150 million people) drink coffee every day, yet Hawaii is the only state in the U.S. that has the proper climate to grow coffee successfully. So it’s no wonder that most people walk right by our beautiful coffee tree in the Butterfly Center without recognizing it as the source of their daily drip!

Harvesting

Harvesting

In order to save time and money, agriculturists have developed machines to do the harvesting of many fruit crops. However, most of the world’s coffee is and will most likely remain a hand harvested crop, for a number of reasons.

First, most coffee grows best at high elevations, usually on the side of a hill or mountain. In extreme cases, harvesters have to secure themselves with ropes just to pick the cherries; such sites are impossible for heavy machinery to access.

Secondly, much of the world’s coffee is grown in developing countries where labor is cheap, so investing in expensive machinery is typically not cost-effective.

Finally, and most importantly, the best quality coffee is made from only the ripest of cherries, as immature cherries impart a bitter and acidic flavor. Ripe cherries can be tucked in among several immature cherries, so it takes a picker with a skilled eye combing through the trees every 8 to10 days to get only the mature red fruits.

While there are machines developed in Brazil that will strip-harvest the fruit off the branches, this process wastes about half of the crop because it is not ripe. Furthermore, the flat land where they are growing on the machine-harvested coffee was once rainforest that has been cleared for farming. This is definitely not sustainable, and should not be encouraged.

While there are machines developed in Brazil that will strip-harvest the fruit off the branches, this process wastes about half of the crop because it is not ripe. Furthermore, the flat land where they are growing on the machine-harvested coffee was once rainforest that has been cleared for farming. This is definitely not sustainable, and should not be encouraged.

FUN FACT: We took three harvests off of our tree this year yielding just under two pounds of roasted coffee.

Processing

Processing

There are two methods for processing coffee beans after they have been harvested: dry and wet.

The dry method is the oldest and most common way of processing coffee. In this method, you take the entire coffee cherry, clean it, and let it dry in the sun for about four weeks with the pulp and flesh of the fruit still on the beans. While this method is simple, it is not recommended for rainy or humid environments.

We therefore used the wet method, which consists of pulping, fermenting and drying. While more labor intensive, this way we were able to make sure no mildew or fungus formed on the beans.

Pulping

Once the coffee has been harvested, the red flesh and pulp of the cherry needs to be removed from the seeds or “beans.” Since the beans have a slimy covering, any pressure applied to the cherry will cause the beans to shoot out, making this one of the easier aspects of coffee harvesting. We simply grasp the cherries firmly, squeeze and voila! — the mucilage-covered beans pop out.

Fermenting

Next, the mucilage coating must be removed from the beans. We let the beans ferment in water for 24 to 36 hours, changing the water and rinsing the beans several times in that period. Any unripe or damaged beans will float to the top of the water during this process and can easily be tossed out. When fermentation is complete, the beans have lost their slimy texture and feel rough to the touch.

Drying

Now that the coffee has been harvested, de-pulped, and washed, it’s ready to undergo the drying process. At this point, the beans still contain a lot of water. Their moisture content needs to come down to about 10 to 12 percent moisture before they can be roasted.

Depending on the climate, this drying process can take as long as four weeks. Drying is usually done on large tables in full sun or in specially-built greenhouses, where the beans are raked or stirred often to make sure they all dry at the same rate.

At the end of this process you will have what is called “parchment” or pergamino coffee. Although coffee beans are sometimes sold and shipped en pergamino (“in parchment”), they still have to be hulled to remove the parchment coating before they can be roasted.

Stay tuned for Part II (the tastiest part!): Hulling, roasting, and enjoying!

And don’t forget to buy tickets to Butterflies and Beans: HMNS’ First Harvest, where you can try our very own Blue Morpho Blend Coffee on January 18!