Tutankhamun has been in the news again, following online publication of Nicholas Reeves’s article that suggests that Tut’s tomb may still be keeping a very big secret: the burial of the king who ruled before him, hidden behind the painted walls of Tut’s burial chamber. To cap it all, this mysterious predecessor, Ankhkheperure Smenkhkare, was probably Tut’s mother-in-law Nefertiti, who changed sex and ruled as king after the death of her husband (and Tut’s father) Akhenaten, in about 1330 BC. No wonder Tut’s life was turned into a miniseries earlier this summer…

Nicholas Reeves knows more about Tutankhamun and his family than almost anyone, so his theory has been widely discussed. His book The Complete Tutankhamun, is an unsurpassed guide to the tomb, and Akhenaten: Egypt’s False Prophet takes a wide-ranging look at the the changes in religion and society that Akhenaten tried to impose as king.

Dr. Reeves’s theory builds on his extensive study of the Valley of the Kings and Tutankhamun’s Egypt, but at its heart are two simple practical observations. Looking at the high-resolution scans of Tut’s burial chamber made by Factum Arte, he noticed vertical and horizontal disturbances in the surface of the north and west walls of the burial chamber. Second, the paintings on the long, northern wall look different from those on the other walls and have been carried out using a different technique.

Dr. Reeves’s suggestion is essentially that the disturbances correspond to the doorways of two chambers that had been sealed off and painted over to conceal them before Tut’s burial. The chamber behind the west wall may have been intended for more of Tut’s belongings, while the chamber behind the north wall could contain the burial of Tut’s predecessor, Smenkhkare/Nefertiti, for whom the tomb was originally made. The paintings on the north wall were executed just after Nefertiti’s burial in order to conceal her mummy and tomb equipment from robbers, a common practice in royal tombs.

When Tut died, nine years after Nefertiti, his own tomb was nowhere near finished. In order to bury him quickly, his burial party used the rooms in front of Nefertiti’s sealed burial chamber. This room then became Tut’s burial chamber, and the three still unpainted walls were painted with scenes of Tut’s funeral and afterlife. The already painted north wall received a few tweaks to transform it from a depiction of Nefertiti’s funeral to Tut’s.

There’s a simple and uncontroversial way to test whether there’s anything behind Dr. Reeves’s theory: ground penetrating radar. Firing this at the walls in question should show what, if anything, is behind them. It sounds as though the Egyptian Ministry of State for Antiquities has given permission. Watch this space!

But first, we should watch the walls. I know little about how one evaluates wall surfaces, so can’t say whether the horizontal and vertical disturbances really are consistent with a couple of sealed doorways. However, I’ve worked on artistic styles – the way representations change over time and circumstance – and I am not convinced by Dr. Reeves’s theory that the north wall of the burial chamber was painted for Nefertiti, nine years before Tut’s burial and the rest of the paintings.

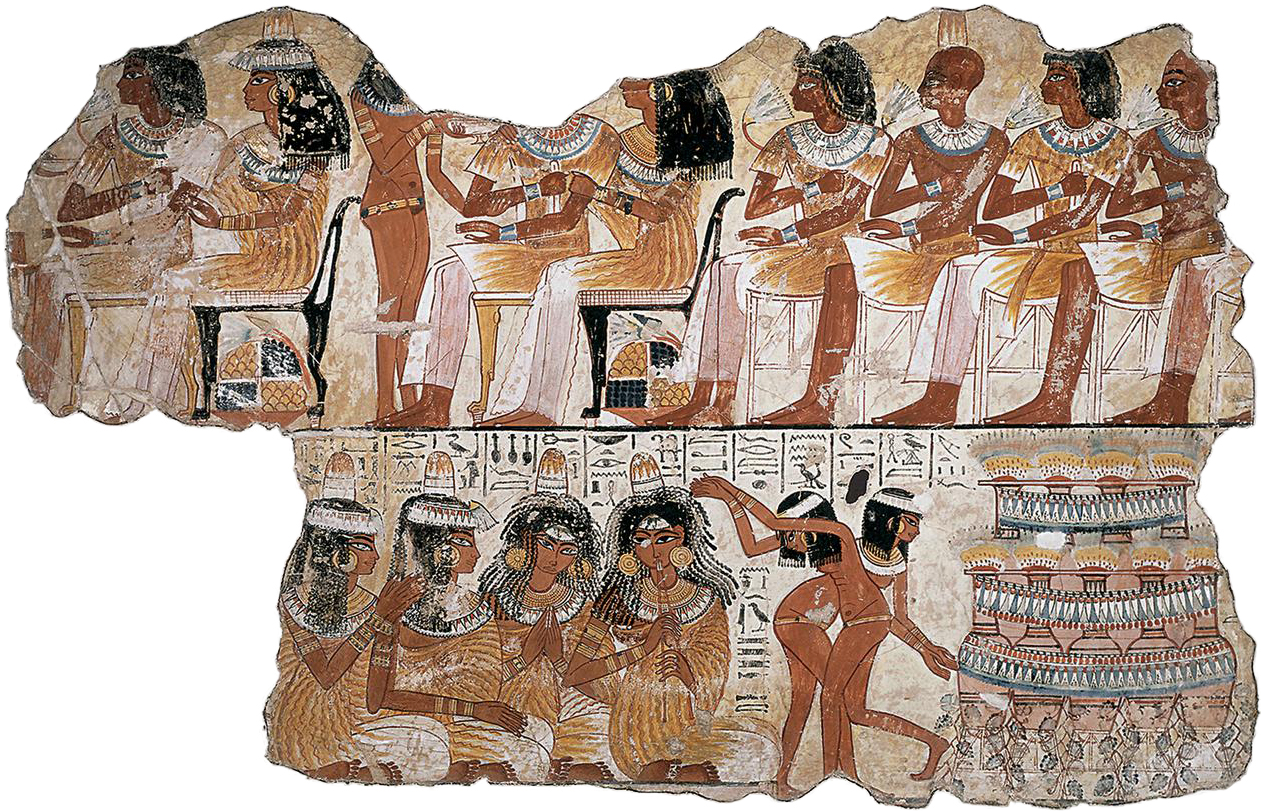

The north wall has three groups of figures. From left to right you can see Osiris, god of the dead, embraced by Tut and his ka (spirit); the sky goddess Nut offering water to Tut; and Aye, Tut’s successor king, wearing a leopard-skin outfit as he performs the opening of the mouth ritual on Tut’s wrapped mummy.

Dr. Reeves argues that images of Nefertiti were painted where we now see Tut, and Tut was painted where we now see his successor Aye. When Tut died, the names were changed to change the identities and the background painted yellow to make the north wall look like the other walls. The figures themselves were not touched, so Tut actually looks like Nefertiti and Aye actually looks like Tut. All clear?

The trouble is that the Tuts don’t look like Nefertitis to me, and Aye doesn’t look much like Tut. Instead, Tut looks like Tut and Aye looks like Aye, as we have always assumed. What is going on?

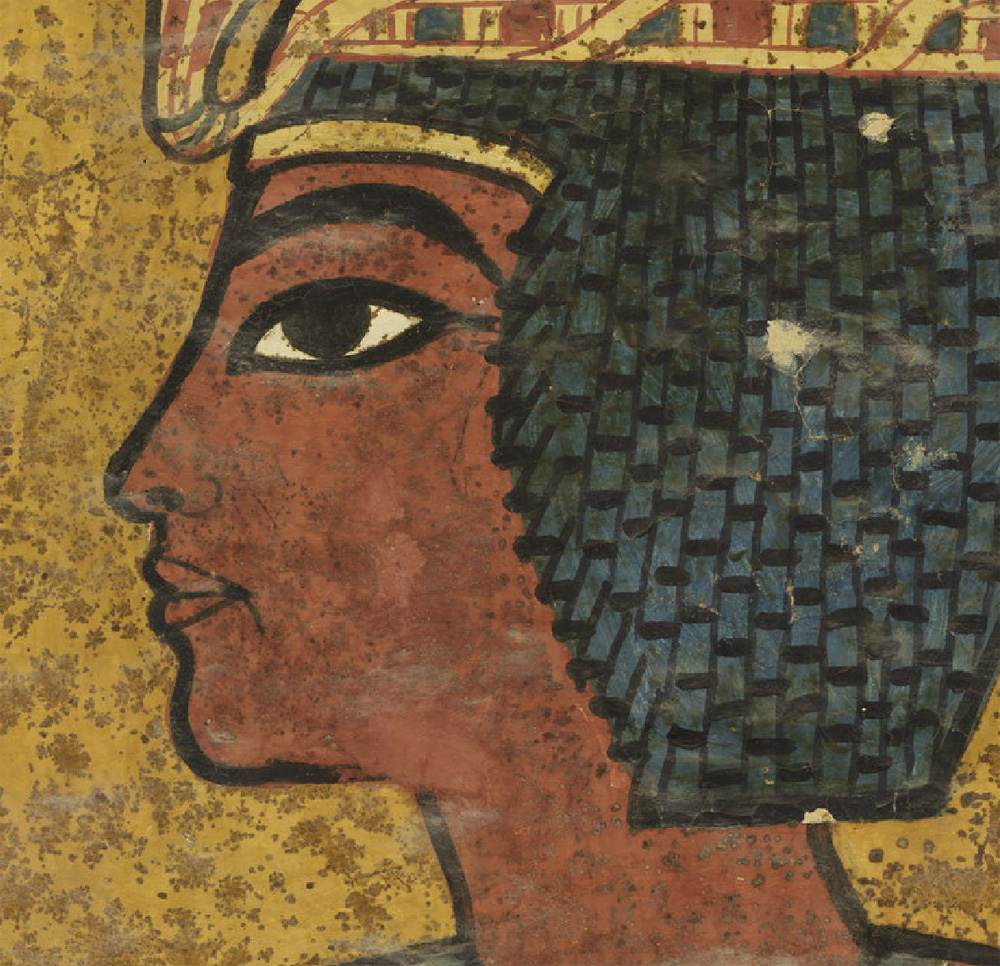

Dr Reeves says that the ‘oromental groove’ – the fold at the corner of Tut’s/Nefertiti’s mouth – is “a defining feature” of Nefertiti’s representations. I disagree. You see them on plenty of representations of other people – male and female – at this time. Here you can see one of Tut’s sisters (and Nefertiti’s daughters) eating a duck and showing off her oromental groove.

It’s harder to tell in 3D sculpture, where you’re carving a subtle groove rather than drawing a single line, but this statue of Tut himself in the Oriental Institute Chicago, seems to have a little groove at the corner of his mouth.

Colossal statue of Tutankhamun from Medinet Habu © The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

And this statue of a god with Tut’s features also has a noticeable fold.

If Tut looks like Tut, and not Nefertiti, then does the painting of King Aye, Tut’s successor, really look like it started out as Tut? He certainly doesn’t look like the Tuts/Nefertitis next to him on the wall.

For me, again, the answer is no. While most representations of people in Egypt are relatively generic – expressing, in part, closeness and obedience to the king – representations of Aye have a number of fairly individual traits. One is a longish, straightish nose which sticks out sharply from a slightly receding forehad. You can see that on the profile of “Aye” in Tut’s tomb as well as this example.

This slightly earlier image of Aye, from the tomb he made for himself before he was king, also shows a similar nose, and a pouch under his round chin.

Dr. Reeves describes “Aye’s” slight double chin as “a feature not present in any image currently recognizable as “Aye” and indicating that the original king painted must have been a chubby young Tutankhamun. Again, I would disagree with this. Just compare Aye’s chin above to the representation in Tut’s tomb. They are pretty similar.

The final object that I think speaks against this hypothesis is a plaster cast of a face taken from a statue of an old man with a heavily wrinkled forehead.

This was discovered in the workshop of the sculptor Thutmose at Akhenaten’s capital, alongside the well known Bust of Nefertiti. The head has no inscription but has often been identified as Aye. I’d agree with this – just compare the noses – but either way, look at his magnificent double chin. At this period, then, double chins aren’t necessarily a sign of youth, but also of age. So this is no young Tut burying Nefertiti, but as the inscriptions themselves say, old Aye burying Tut.

You can see that I’m skeptical of Dr. Reeves’s interpretation of the wall paintings. Does this mean that there’s nothing behind the wall(s)? Not necessarily. The wall paintings form only one part of his hypothesis, and I don’t know enough about structural mechanics and architecture to be able to decode or comment on the surface features he has identified as plastered-up doorways. So I’ll be very interested to see what the results of the ground-penetrating radar examination reveal, and I’ll be delighted if my skepticism is shown to be mistaken. Using radar is only the start of what could be a long process, though. Any anomalies revealed may be something very different from chambers full of gorgeous gold. For example, the floor of the Valley of the Kings is shot through with cracks and fissures which show up on radar as anomalies; the soil of the valley has been churned over by two hundred years of excavators, and is also full of modern holes. There are plenty of unfinished niches in other tombs, and perhaps Tut’s architects just neatly plastered over two in the burial chamber. We’ll just have to wait and see.

In the meantime, there’s plenty of Tut and Nefertiti (sorry, but no Aye) in the Hall of Ancient Egypt at HMNS. In addition to our head of a god with the features of Tut, and our replica of the Bust of Nefertiti, come and look at this amulet.

It is tiny, about the size of a little fingernail, but the faience paste has been molded in some detail. You can make out a crouching figure clad in the long pleated kilt of the elite of the time of Akhenaten. The figure has one hand lifted to its mouth, sucking its index finger in the gesture used to identify children in Egypt. On its head is a skull-hugging cap with streamers hanging down the back, and a protective uraeus snake at the front. This is a royal person of the Amarna period reborn as a child, just as the sun rises again every day. The cap crown worn by the figure is worn by only one person: Nefertiti. Even if Nefertiti may not be awaiting rebirth in her hidden burial chamber, you can see her reborn every day in the Hall of Ancient Egypt.