In 1817, Scottish inventor and optical scientist Sir David Brewster invented a tube with opposing mirrors running through it and beads of colored glass in one end. He called it the “kaleidoscope,” a word whose Greek roots mean “beautiful shape viewer,” which most of us have peered through and hooted in awe at around kindergarten age. It’s a simple design that capitalizes on a trick of light to incredible effects. Three mirrors arranged in a triangle reflect the light entering one end of the scope down the tube and across to each other. By the time it reaches your eye, it has reflected so many times it creates the effect of a precise geometric pattern that infinitely changes.

Back in the nineteenth century, when optics were a new thing, this wasn’t just awe-inspiring for children; even adults were impressed. But Sir Brewster neglected to patent his kaleidoscope, and others copied the new technology and began manufacturing it as a child’s toy, likely costing him millions in potential income and in reputation. Good thing he had other inventions to lean on.

Sir Brewster is responsible for inventing the first portable 3D viewing device, which he called the “lenticular stereoscope.” He built the first binocular camera, the lighthouse illuminator, the polyzonal lens, and two types of polarimeters, a scientific instrument used to measure the angle of rotation caused by passing light through an optically active substance. This last device is used in the chemical industry to test the properties of new substances.

In 1972, the kaleidoscope’s potential was pushed a step further. John Lyon Burnside, III and Harry Hay patented a version of the geometry-creating tube that scrapped the bits of colored glass and replaced it with a spherical lens, allowing the viewer to point the viewing tube at any object in nature to see it reduplicated across the mirrors in the same way. They dubbed it the “teleidoscope.”

At the Houston Museum of Natural Science, we sell both kaleidoscopes and teleidoscopes in the Museum Store. As a lover of photography, nature and geometric patterns, I experimented with this teleidoscope and my iPhone and captured some amazing images in the Cockrell Butterfly Center, the Cullen Hall of Gems and Minerals, and other locations around the museum. Some things work better than others, but for the most part, everything looks incredible through one of these bad boys.

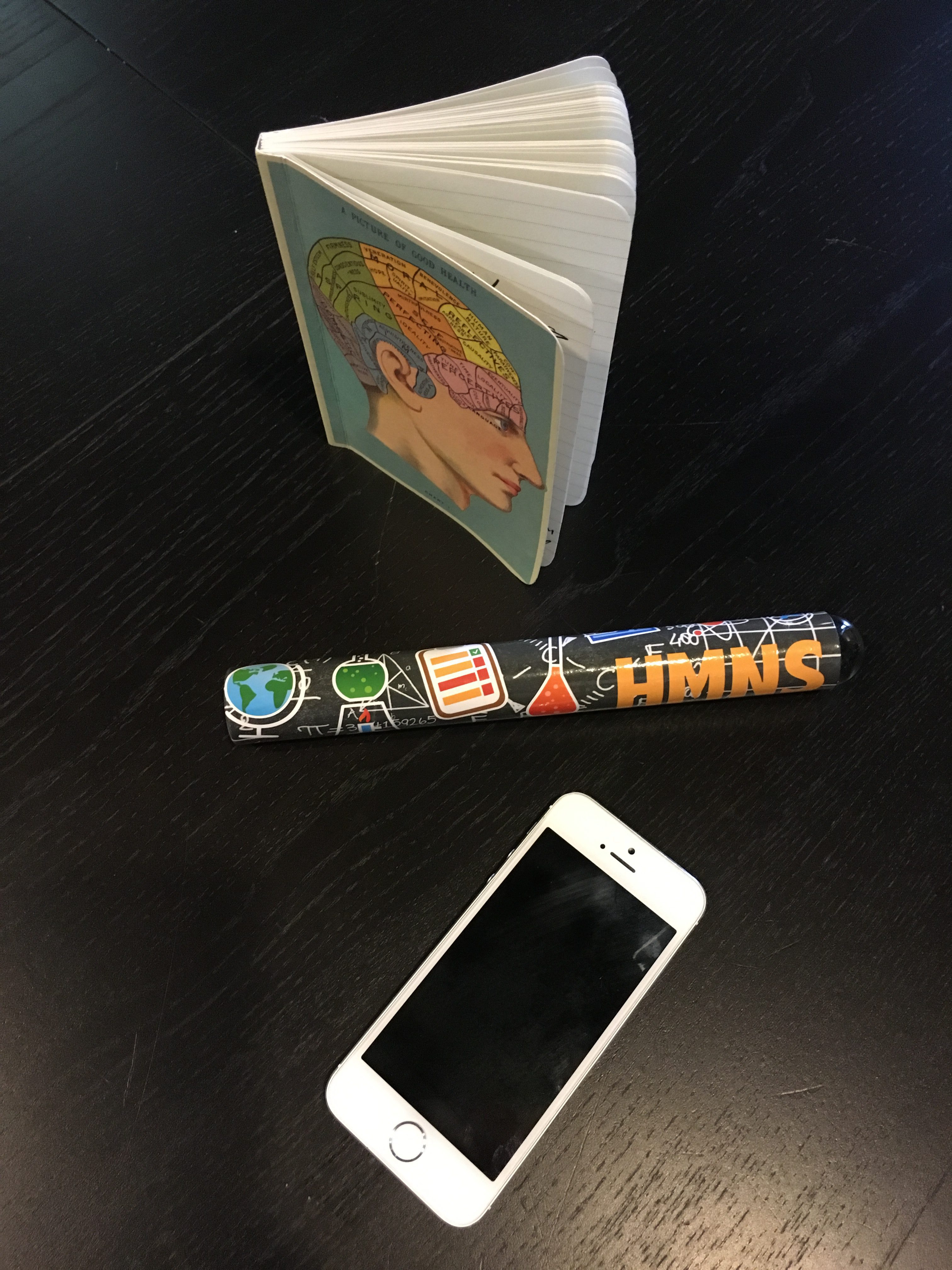

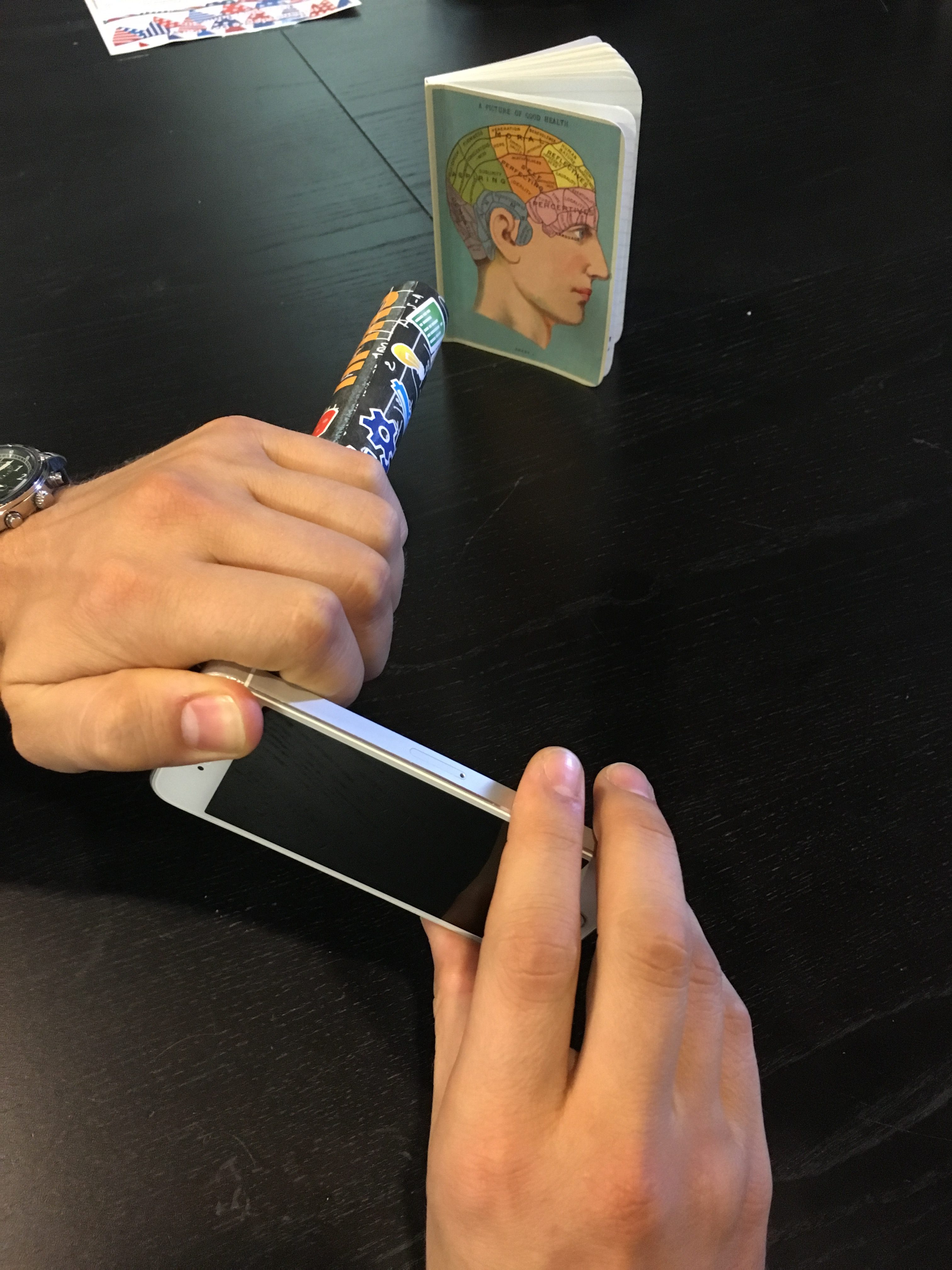

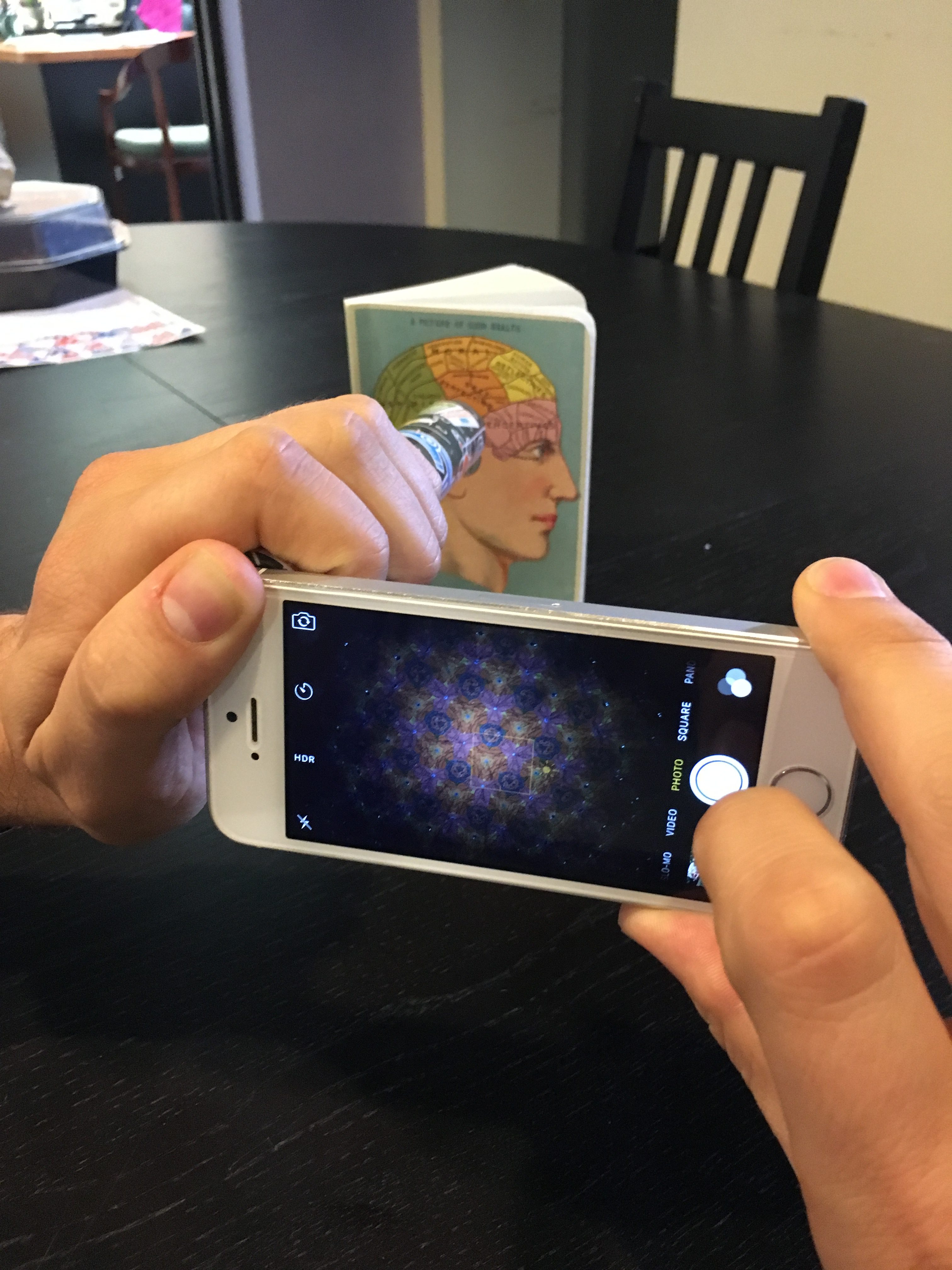

Here’s how you do it, in photo steps. (You can get this awesome notebook at the Museum Store, as well.)

Grab a cool thing to take a photo of (or just go outside), and bring your teleidoscope and your smart phone or digital camera.

Hold the viewing end of the teleidoscope against the lens of your smart phone or digital camera. Make sure it’s tight and that there’s no light leaking around the edges. It takes some practice, but you’ll learn quickly.

Align your shot and snap it when you see a pattern you like. The edges will appear darker than the center. This is yet another property of light as it bounces around inside the scope.

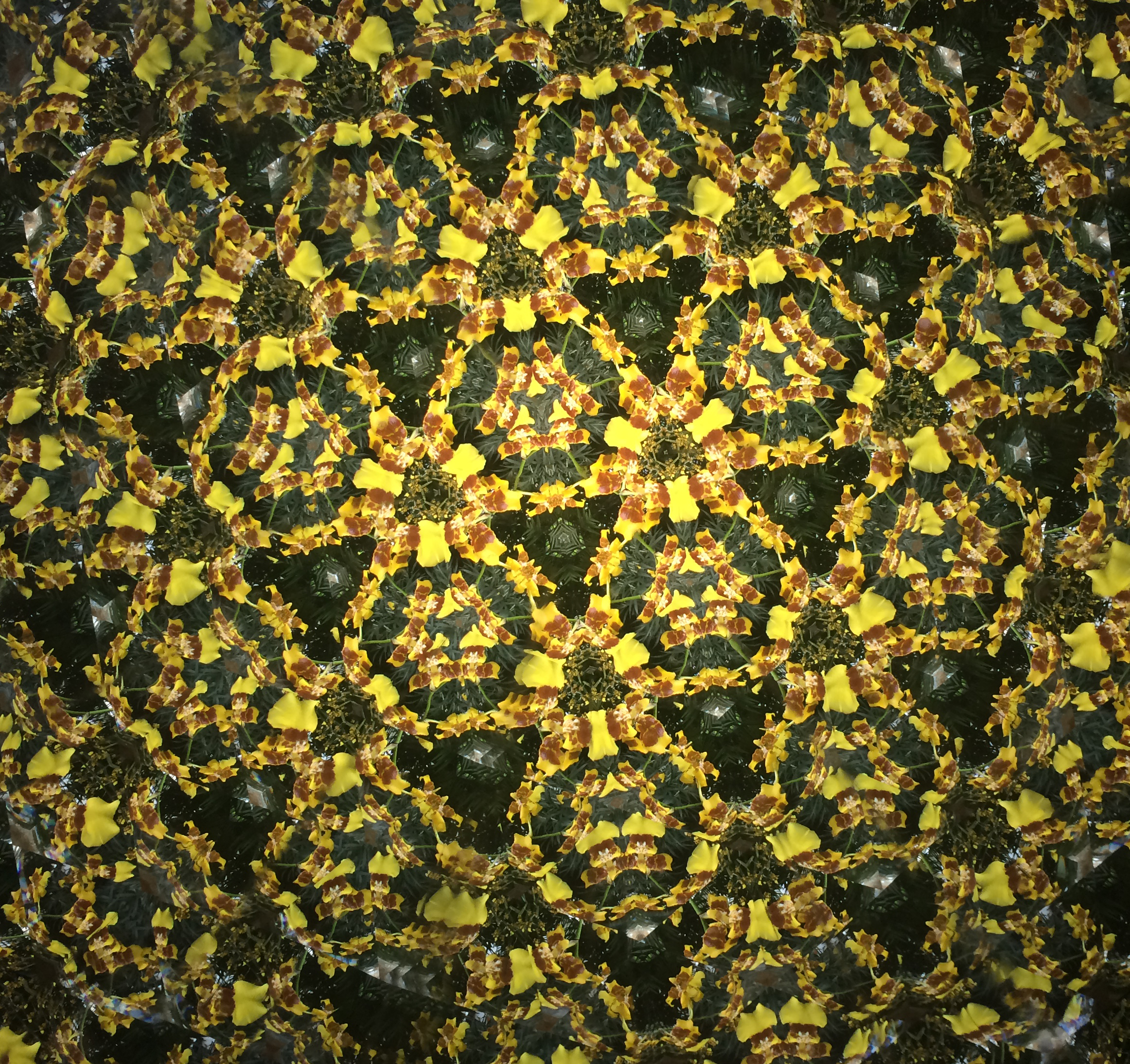

And here are some of the images I made, cropped down to a square, eliminating the dark edges. What do you think?

Everything looks better through a teleidoscope! So buy one or make your own, and post your images on our social media. Your images look even better with Instagram filters! Don’t forget to tag us with #hmns and @hmns. We’d love to see what you come up with.