I love my job. Not everyone can say that. My avocation and vocation are as two eyes with one sight (paraphrasing Robert Frost). Part of that job was taking a group of 15 patrons up to the Museum’s dig site outside Seymour, Texas. There, under the tutelage of Dr. Robert Bakker and David Temple, the group learned how to properly excavate bones of ancient animals — in this case, Permian synapsids, amphibians, and fish.

I got to go through a spoil pile (the pile of debris and castoff that others have thrown aside), and found several bits of our very early ancestors, the synapsid Dimetrodon. I also worked on removing the overburden (the rock and dirt that is over a site we want to excavate), and found bits from a dorsal spine of a Xenacanthus, an ancient shark. It was the fulfillment of a childhood dream (as I child I played paleontologist rather than fireman and my first Deinonychus is still buried out back at my childhood home).

But I’m not the only one who dreamed of finding fossils in Texas.

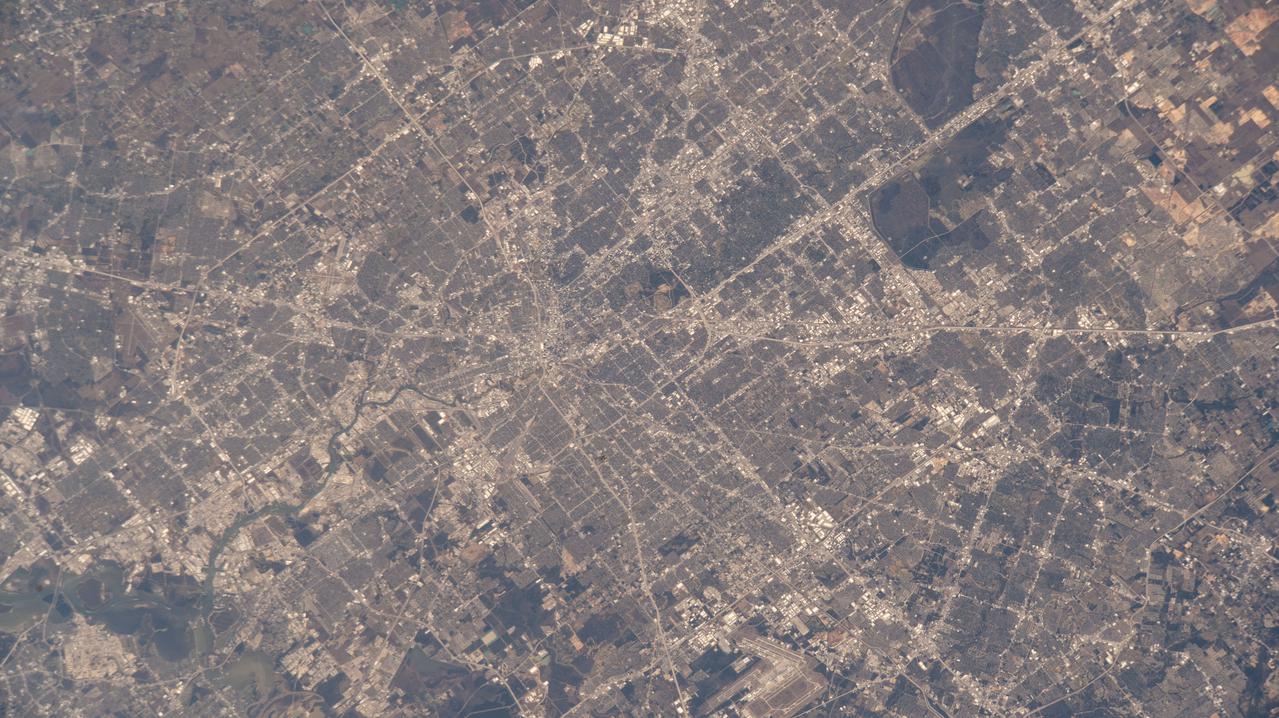

Noted Swiss naturalist Jacob Boll came to Texas in 1869 to join La Reunion commune that is located in the current Reunion District of Dallas. (The Reunion Tower is named in honor of that small settlement.) La Reunion commune was responsible for the first brewery and butcher shop in the Dallas area. It also helped Dallas become the center for carriage and harness making.

Noted Swiss naturalist Jacob Boll came to Texas in 1869 to join La Reunion commune that is located in the current Reunion District of Dallas. (The Reunion Tower is named in honor of that small settlement.) La Reunion commune was responsible for the first brewery and butcher shop in the Dallas area. It also helped Dallas become the center for carriage and harness making.

Jacob Boll came over to set up high schools based in scientific inquiry. Through the late 1870s, he searched for fossils for Edward Drinker Cope, the noted “Bone Wars” paleontologist. Boll found over 30 new vertebrate species from the Permian period, which can be seen in the collections of the American Museum of Natural History. Unfortunately, on his last trip, he was bitten by a rattlesnake, wrote some final letters to his family, composed a short poem in German, and died.

In the Permian period, Texas was very different from today. Near Seymour, there were rivers and seasonal flood plains. However, even with this picture, there are still unexplained factors about the life of Dimetrodon — one being that there was not enough prey to sustain the population that we have found in the fossil record. While the Dimetrodon were making sushi out of Xenacanthus and chewing on some Trimerorhachis legs (like frog legs, only much shorter), there was not enough food to go around.

Now add to this case the curious fact that almost no Dimetrodon skeleton found has an intact tail. Anyone who has been to a good Cajun restaurant will know that the best meat on an alligator is the tail. And Dimetrodon would agree — hence the lack of tails.

But even this does not account for all the food necessary to keep all the predators alive. Where is the missing food?

Dr. Bakker gave us a couple of hints as to what he thinks is the answer.

A few miles away from the site, there is an old Permian river basin where we find Edaphosaurus, a large Dimetrodon-like herbivore. Was it possible for Dimetrodon to walk a few miles, ambush an animal about its size, then walk back for a rest? This would provide food for the population.

If you are interested in learning more about the Texas Red Beds, join us for our Fossil Recovery Class on May 20. You can go through some of our collection from the trip and learn about fossil collecting and identification techniques.

Click here for more information.