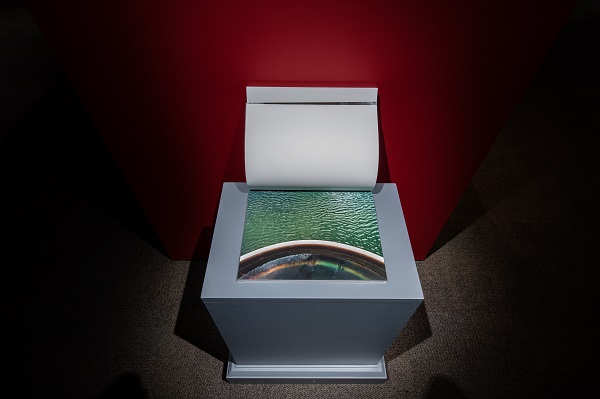

Brad Temkin’s exhibit, showcasing the underappreciated resource we all have in common has been displayed in the Hamill Gallery for over a year now and, oh, what a year it has been.

Little did we know that State of Water: Our Most Valuable Resource would become even more essential than it was when first installed early last year. When the city of Houston believed itself to see the light through the trees of 2020, February brought a catastrophic freeze. Water, a resource so readily available to the masses, proved paramount. Some Houstonians were without running water for days, some for weeks. Every day routines were interrupted and the most simple tasks were taken for granted.

With Beyond Bones we have covered photography from how-to focus stack to helping us dig deeper in uncovering prehistoric finds, but sitting down with Brad brought forth so many important questions that help us see the previous months through more open eyes.

Where are you from and how did you find photography?

I grew up in the Chicago area. My interest in photography came from music. I was a rock’n’roll photographer. It was just magic from the very beginning. In high school, I went to a lot of concerts where I would photograph, and met some people in the music industry. I was lucky, and I did some work for the Chicago Reader and then Creem Magazine, record companies and concert promoters…sort of like the film Almost Famous. I wasn’t star struck and they liked that, so I had access. It was a blast!

Did you know early on that photography was going to drive your career?

In 1973, I saw an exhibition by Minor White, and it was like visual poetry. It turned my world upside down and I began making pictures that were more poetic and more expressive. I went to college for photography, and decided that’s what I wanted to do with my life. Art and not commercial. I was more interested in art and I did other things to make money.

Being that you’re a professor at Columbia College, do you view photography and education as entities that go hand-in-hand?

Absolutely! What it’s done for me is it’s shown me my intent and awareness for the world around me. So for me, that’s what I try to teach my students. The connection between them and picture-making. It’s less about finding a job. If you can can frame, compose, and technically master the craft of photography, you can do commercial work. But if you can do commercial work well, that doesn’t necessarily mean you can find that connection. I think that’s because commercial work is more about money rather than personal. The connection between my life and making pictures has always been first and foremost.

Does that tie into why you find educating through photography to be so important?

Trying to learn something about a subject has always fueled my projects and I think a camera always gives you unfettered access to look at things and stare at things closely for a long period of time without being considered a nut job. What happens is when you start to make pictures, you look at the world in a different way. You’re looking at shapes and forms and you notice things like light. Not that everyone else doesn’t notice those things, but I think that when you put them together you kind of think of them in how can you sum up what you see between four edges of a frame. In sharing my enthusiasm for learning things and how I go about it, my hope is to spur others to learn about themselves and the world in which we live.

So it’s safe to say the education found within the four edges comes before beauty?

Actually, beauty is very important to me. It’s the sharpest tool in my box, and it invites people to look at the subject for a longer time. I want people to ask questions. I don’t want to give people answers. The questions are way more important than the answers. In fact, the answers always change. There is no right answer. To be able to get a sense of surprise and wonder from the world and then maybe ask a question about it, you learn about that subject and make your own decision. I just believe people eventually make the right decision.

Being that this is a topic that most don’t know much about, guests, myself included, have been intrigued by the beauty found in your photos and then the questions pop up. So your intent looks to be working.

Thank you. Right, they don’t know about it because they never think about it. When infrastructure works, you never think about how it works. What happens when you flush the toilet? What happens when you take a shower? It’s just taken for granted. What happens when you run out of water? It’s really important to ask these questions, and then when you ask them you start to think about your effect.

When you’re out in the field doing these shoots, what architecture and/or landscapes are drawing you in?

Early on, it was just nature. As I became more aware, I found the world was way more interesting than myself. My belief is that we need nature in our lives. We have gardens, keep house plants and pictures of beautiful pastures in our living space. It makes us do better work, but it’s the relationship between us and nature that’s really important to me and how we accommodate it, and how it accommodates us.

This appreciation is definitely apparent in your Rooftop series.

Those pictures were showing gardens which most people would think of where you sit and meditate or have a drink or read or whatever and these gardens were not used for that. These gardens were made to mitigate our carbon footprint by insulating the buildings by creating storm water management because of the pervious surfaces. I like the way we fix things and how we are affected. I was looking at buildings that became part of the landscape. The photographs became landscapes as opposed to being architectural.

While you were working on Rooftop, were you thinking ahead to The State of Water?

As I photographed Rooftop, I learned about storm water management and wanted to do something with it. When I finished up the Rooftop project, I thought water was something that I’ve photographed since making my first pictures. I loved to watch the transformative quality of water. I would love to be able to capture that. The State Of Water was fueled in capturing the magic that happened when we took waste water, raw water, etc., and purified it for our use. We take it for granted, and I thought it would be visually exciting to bring attention to it.

So why ‘The State of Water’?

I called it The State of Water because it can be looked at as all different things. Water has all different states. I love the way it looks, the way it feels, the way it sounds, and we need it to exist. We use it for life! Everything that goes into us goes back into the Earth, and the Earth provides our food, oxygen, and water…so it’s all about sustainability and that cycle. That’s what I hope people see, so they can ask questions about that and respect it.

Spending so much time around heavily textured settings, do you have a special appreciation for engineering feats that some people may glance over?

I love the way we engineer things, and when infrastructure works like its supposed to, you never have to think about it. The people in the industry that have seen my pictures told me they never looked at it in this way. They’re grateful to look at it with a visual kind of awe, and I am in awe of how we fix things. This is one of the things that drives my work. My philosophy is that when we’re at our worst, or a dire crossroad, is when we become our best. When we have to solve a problem, we do it. It shows our humor, our ingenuity, and grace and that’s what I hope my pictures show.

You touched on how people in the field look at your pictures and see things in a different light, do you see everyday objects differently because of your own work?

Yes! I look at the world differently because of my work. I think I’m a bit more open and it has made me more mindful about the things around me and my affect.

Is there anything new that you would like to dive into for your next project?

I know I want to stay with water and nature and our relationship with it for now. If you look back, all these projects are pretty much blending into each other and many of them are done at the same time as each other, but I never want to redo myself. That’s my goal. What lies ahead? I have to believe I’m not dry yet.

This exhibition was created by Brad Temkin and the Field Museum. State of Water: Our Most Valuable Resource is supported by the Phillip and Edith Leonian Foundation.