They say that “seeing is believing,” but you’d be wise to trust more than just your eyes. Mike Eklund, Research Associate at the University of Texas, recently conducted a training session in the museum’s fossil prep lab, and he told a story of just how much our eyes can deceive us. A university’s paleontology collection accepted the donation of a seemingly intact Asian rhinoceros skull fossil. What luck! The new addition would be an excellent tool for scientific study and teaching. However, when Eklund imaged the fossil, he found that the skull had major restoration and was likely less than 50% original. The rest was artistically sculpted.

Photography Meets Science

Revealing some of fossils’ unseen details occurs in a process that took Eklund six years to develop. During the fall of 2018, he along with two other researchers, Arvid Aase and Christopher Bell, published a paper about the imaging technique they’ve dubbed Progressive Photonics. Through the method, a systematic series of images are taken, using different light sources and direction to illuminate the specimen. The camera stays fixed directly above the object, and the only variant in each photo is the type of lighting — direct visible, polarized, oblique and ultraviolet (UV).

Paleontologists analyzing fossil specimens without the use of Progressive Photonics typically encounter three problems. Many fossils are indistinguishable in color or texture from the rock, or matrix, that surrounds it, making it difficult to interpret information from the specimen. Soft tissues and other important biological information are often present but impossible to identify in visible light. Human intervention — like the plaster, paint and adhesive found on the rhino skull from earlier — can be virtually invisible. Together, the lighting techniques in Progressive Photonics aim to improve the visibility of these imperceptible features along four aspects: clarity, reflectivity, three-dimensionality and chemistry.

Shed Some Light

The process begins with a baseline image under direct lighting. By including a Munsell palette color calibration card and a reference cube labeled with measurements and light type, the shot establishes scale and color. From there, other images are taken, each under different lighting conditions.

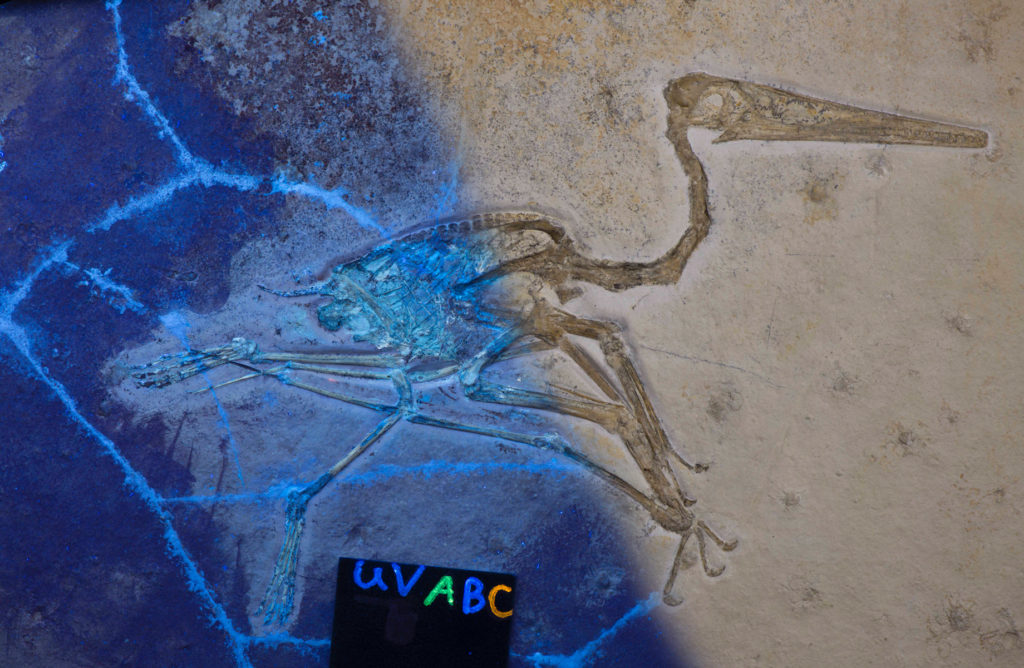

One light source in the process that gets a lot of attention is the UV spectrum. This lighting causes some materials both biological and manmade to fluoresce, or glow, while other substances react differently to the light, highlighting distinctions between fossil, rock and manmade materials. The technique is useful for differentiating the chemical makeup of materials on the specimen.

“The naked eye doesn’t tell enough of the story.” Eklund reminds us. Sometimes evidence of biological structures, such as skin, internal organs, connective tissue and feathers, is preserved, often existing more like a stain on the rock than the tangible fossil bones alongside them. Eklund has imaged prehistoric sharks, animals composed mostly of cartilage, and been able to trace where actual soft tissue ends and the matrix begins. This minute biological information was thought to be incredibly rare, but Progressive Photonics reveals that it’s much more common than we thought, finding it in previously overlooked and freshly unearthed specimens alike.

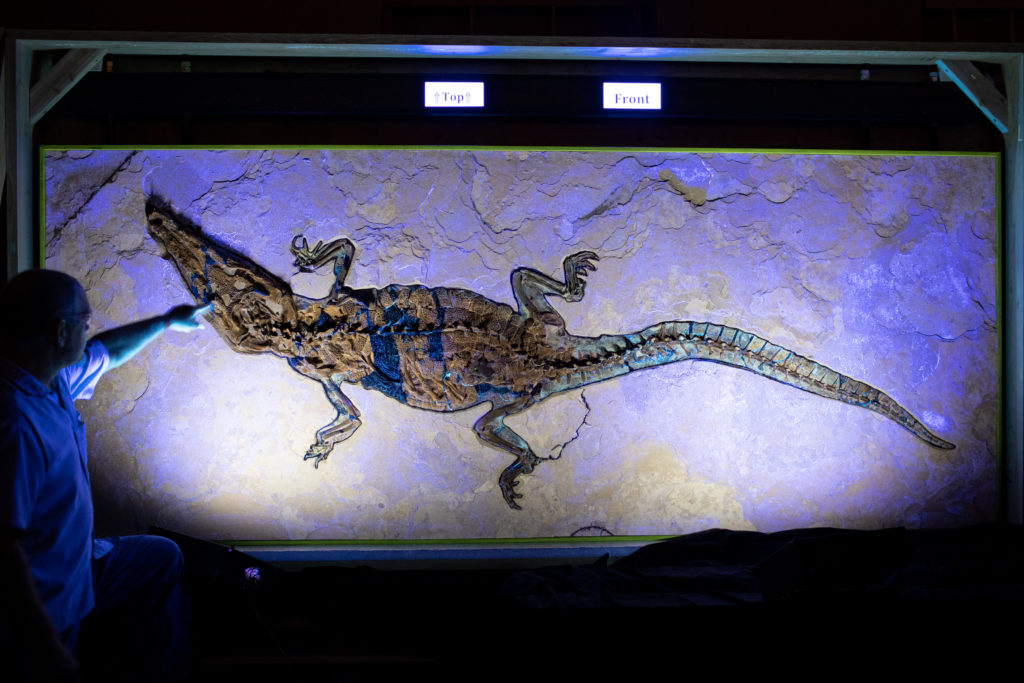

Not nearly as flashy as its UV counterpart, capturing oblique lighting is another part of the Progressive Photonics process, and for Eklund it’s even more important. The technique uses angled lighting to cast controlled shadows uniformly across the specimen. The improved contrast and relief highlights three-dimensionality and illuminates important structures on the specimen. Scientists can better draw conclusions about a fossil’s texture and cracks from a world away. Polarized lighting, the third type, reduces glare and increases contrast and saturation, making details pop.

Ultraviolet light in paleontologic research has been documented as early as the 1920s in France, but its use was never standardized, and many paleontologists weren’t even aware of its application. “We didn’t invent any of these lighting techniques,” Eklund humbly remarks, “But what we have done here is create an affordable, universal strategy that institutions can use to record and investigate the history of their specimens. It is a simple, standardized formula, which generates much higher quality data using superior, modern equipment.” The result of Progressive Photonics is a catalog of unedited, digital images that scientists can flip through and identify unique features.

The F Word

We don’t use the F-word at the museum. It’s a rule I learned from Staff Trainer and Discovery Guide James Washington. “Nothing in the museum is Fake,” (Yes, that’s the big F-word.) Washington reminds me during a tour of our dino exhibits in the Morian Hall of Paleontology. “There are objects that may be recreations, but no matter what, it’s based in science.” Words like replicas and casts more accurately describe any non-fossils you see in our hall. Museum replicas are copies of actual specimens, and any piece of a fossil that isn’t, is a synthesis of scientific hypothesis and theory. Nothing is pulled from thin air.

Human modification is an interesting aspect of this. At times, museum acquisitions can be a gamble. An outwardly superb fossil specimen could house a plethora of “tweaks,” some that render the object more of an art piece than an academically viable object of study, like that rhino Eklund imaged. You see, as much as fossils can tell us about prehistoric flora, fauna and environments, each specimen contains two distinct histories: one that started millions of years ago when the animal lived, and one that only began when the fossilized object was unearthed. The truths of that recent history can be just as elusive as the ancient.

“This whole technique isn’t meant to be a dogwhistle,” Eklund explains. “It’s important to understand the history of a fossil, so you can identify what is biological information and what is not.”

Some restoration work doesn’t necessarily render an entire specimen worthless. Our Associate Curator of Paleontology David Temple showed me some of the specimens that have been documented using Progressive Photonics. “We’ve imaged about 10 in our hall so far, and we have plans to document more [fossils] using Mike’s process,” Temple says, “eventually the entire hall if we can.”

Three of those specimens were dactyls — one even had spectacular soft wing tissue. “Which is remarkable,” David says. Another looks like it ought to have soft tissue, but instead just has a cosmetic sculpting in the rock, where its preparator might have guessed its wing membrane might be. “But that doesn’t mean you can’t study it. You just couldn’t conclude anything about its soft tissue, but you can still learn a lot from it, like its eyes and beak and wing joints.” It does have pretty remarkable teeth.

“Progressive Photonics gives us a far more complete picture of a specimen,” Temple says. The better we understand the recent history of a specimen, the more accurate conclusions we can draw about its prehistoric story. It’s part of a long-term perspective to preserve the scientific information of our collection as fully as possible for this generation and the next.

Learn more about Progressive Photonics at Mike Eklund’s lecture Hidden in Light on Monday, January 27, 2020 at 6:30 p.m. Get tickets here!

Science is happening every day at HMNS! Our team uncovers and prepares ancient fossils in our paleontology prep lab every day, and you can watch the science in action with a visit to the Morian Hall of Paleontology.