By Dr. Michael Tinkler, Associate Professor of Art and Architecture, Hobart and William Smith Colleges

The good news from Paris this week is that medieval builders worried about church fires. Remember, all light before Edison involved open flame – whether torches or candles. Candles in churches today are mainly symbolic, but reading inside churches called for artificial light. Lightening hit church towers and careless roof repairs sometimes caught beam work on fire. Both exterior and interior fires needed to be guarded against.

Before the late 11th Century church roofs tended to be exposed wooden truss systems, sometimes with a flat wooden drop ceiling.

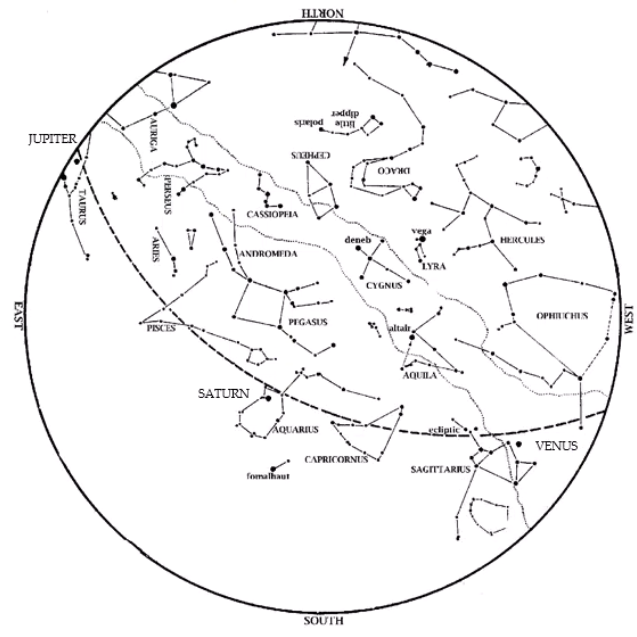

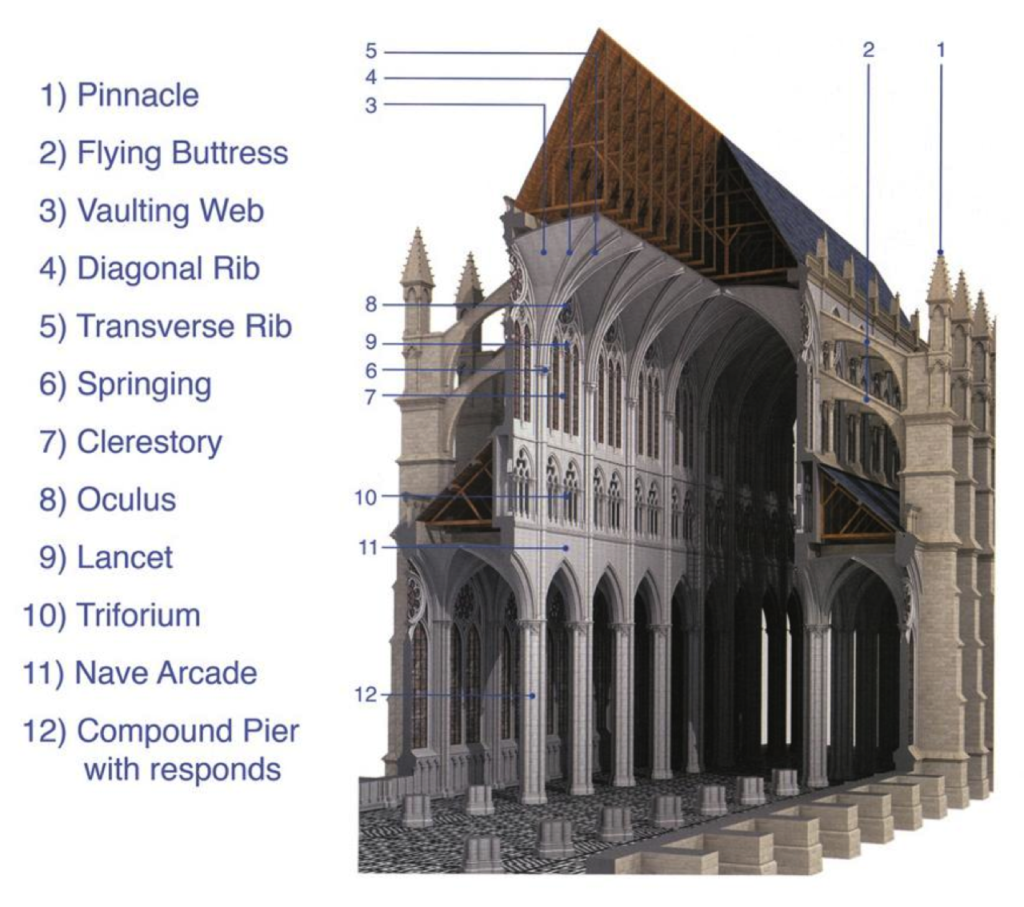

Earlier churches began to be rebuilt with stone or brick vaulting or planned with vaulting after 1075. The first 50 years or so of vaulted architecture tends to be identified as the Romanesque style, with early Gothic starting in 1140. Notre-Dame in Paris was begun in 1163, and was planned with stone vaulting.

Gothic rib vault in the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris, France. Author:

Carlos Delgado. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Scholars argue about the intention behind the expense of stone vaults. Was it for the acoustics of the chanted liturgy? Was it competition between members of the elite, that they could afford the best for their churches? Or was it for the function of fireproofing? I tend in teaching my students to encourage them to embrace the healing power of “and.” Taller towers look more impressive and allow the sound of bells to carry further. Flying buttresses carry weight away from the roof to exterior supports and brace upper walls against the force of high winds. Stone vaults help chant sound better and provide a double fire barrier.

The stone vaults at Notre-Dame, as we saw in photos and videos this week, served as a barrier against the flaming forest of roof beams. The largest hole in the vaulting seems to be where the spire crashed through – not a failure of the vaulting per se. I’m certain the architects and engineers working this week after the fire are concerned about well the vaults are doing at exerting outward lateral pressure against the walls, which could lean and collapse into the center of the building.

However, the stone vaults have also protected the roof beams for 850 years against fire from inside the cathedral. When drifting sparks and cinders rise as high as the 115 feet of the vaults, they encounter not a wooden ceiling but stone.

So if the wooden roofs are a continual (if low-grade) fire risk, why build them at all? Climate! The stone vaults are not particularly water proof, and would have to be covered anyway. In Northern Europe, that means a high peaked roof for rain and snow. A few years ago I made a first visit to Sevilla, Spain. While climbing the famous La Giralda tower I looked down at the roofs of the cathedral and was surprised to see exposed Gothic vaults like irregular domes, concealed behind parapet walls from viewers below. I asked about this feature – or absence of what I considered a standard feature of Gothic architecture and was told that it rains so little in Sevilla they don’t bother with roofs and instead apply a thick casing of concrete to the exterior of the vaults.

Further Reading:

Love and Architecture: A Story of Houston’s Skyline

Rice University Architecture Scavenger Hunt

The Krak Des Chevaliers: A Tough Nut to Krak