The world is a vast place, but all life living on its surface sprung from the same origins. Everyone and everything on this planet is connected. Sometimes the connections may not be readily apparent, but they are there..

Our “Missed Connections” series is all about exploring the unexpected connections between objects in our different exhibits. Today we are looking Spondylus shells (also known as spiny oysters), which appear in our Hall of Malacology and our Hall of the Americas.

Spondylus is a genus of bivalve molluscs known for their vibrantly-colored, often spiny exteriors. The spiny subspecies are often referred to as “spiny oysters”, though they aren’t true oysters. They can be found in both the Old World and New World and have been used to make jewelry by numerous cultures in both hemispheres since paleolithic times. The unusual spines that protrude from the exterior of certain subspecies function to ward off predators.

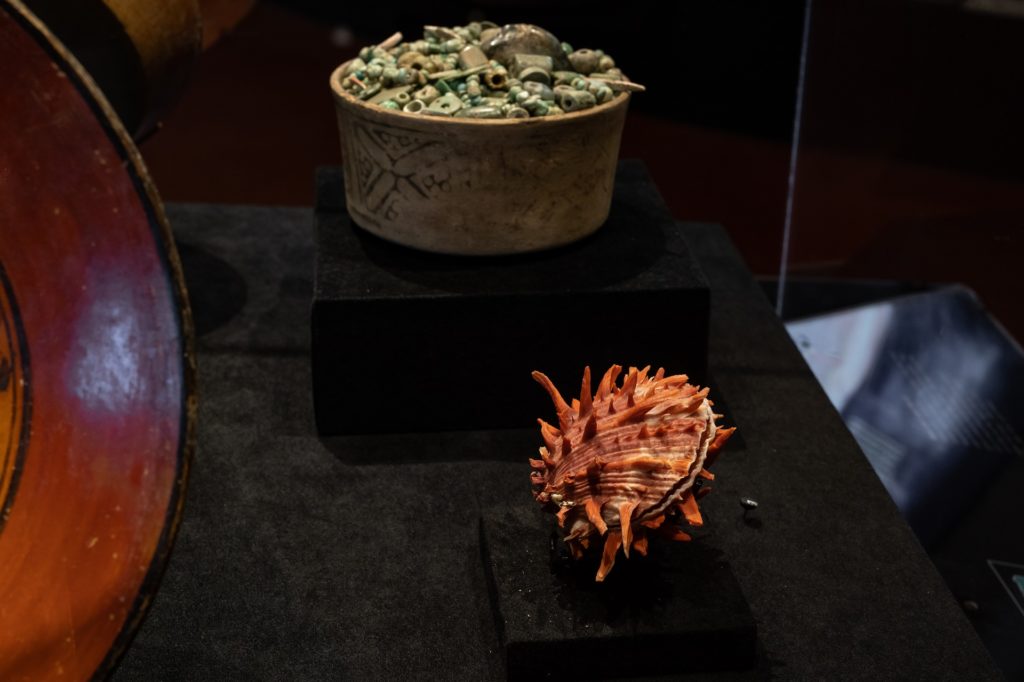

In the New World, Spondylus shells are found both in the Pacific and the Caribbean. Shell beds lie anywhere between 13 to 165 feet beneath the surface. In ancient times these shells were considered as valuable as gold by cultures like the Maya and the Inca. In the Maya section of our McGovern Hall of the Americas we have on display a beautiful Spondylus shell and an offering vessel filled with jade beads (also considered exceptionally valuable) and Spondylus spines. The Spondylus shell is a modern specimen placed there to give visitors an idea of what the complete shells look like. The spines in the vase, however, are original and date to between 400 and 900 AD.

The Maya used the shells to make a variety of objects, including beads, amulets, gorgets and figurines. Spondylus shells functioned as currency within ancient Maya society; they could be traded for anything. They have been found buried alongside Maya kings and nobility both in their raw form, and in the form of jewelry and small-scale sculpture.

It may sound crazy that the Maya were using marine shells as currency, but even today good Spondylus specimens in rare colors can fetch a high price among collectors. These days, it’s much easier to acquire Spondylus shells thanks to modern scuba gear, so a specimen has to be exceptionally rare and beautiful to fetch a big price, but for the Maya, getting ahold of these shells was much harder. Back then, divers would search the shallow seas for them without goggles or breathing equipment.

Once collected, the shells would would either be made into beautiful jewelry or sculpture for the local elite, or traded inland for precious materials such as jade or obsidian, which are more rare and valuable on the coast than Spondylus shells because they come from far away inland sources. Just like collectors today, the Maya valued Spondylus for its rarity, so it’s value increased the further away it got from the coast. The shells were sometimes also traded for necessities like salt or raw materials to make stone tools with. They functioned a bit like modern money, except that their value changed depending on how far away from their source you were.

In the 21st century Spondylus is still a popular raw material for jewelry making and rare specimens are highly sought after by collectors. Some of the same shell beds that the ancients collected from are still being exploited by modern divers. Scuba gear makes today’s divers much more efficient. This is good for the industry, but not so great for the environment. The city of Salango, which has been a hub for the Spondylus industry since before Inca times, had a fishing ban placed on its surrounding waters in 2009, partly due to over exploitation of the shellfish.

The specimens on display in our Hall of Malacology are from the Phillippenes. Each of these vibrantly colored specimens if a paratype for their subspecies and therefore extremely important specimens. Paratypes are the designates specimens researchers use to describe a new species. They were found in 40-60 meters of water off Nonocan Island.

Spondylus shells are a great example of how an object can hold different meanings to different fields of science. They are values by collectors and marine biologists for their diversity while archaeologists value them for the insight they provide into ancient societies.

Want to learn more about the amazing ways seemingly disparate creatures and cultures are connected? Come visit the Houston Museum of Natural Science!