God Speed by English artist Edmund Leighton, 1900: depicting an armoured knight departing for war and leaving his beloved

Everyone knows that Chivalry is dead. But what are the real symptoms that the famous code of honor is no longer adhered to in our society and should we really be sad about that? These days most of us equate chivalry with holding the door open for ladies, pulling out a chair for a lady, defending a lady’s honor, and in general showing women that they are worthy of your attention and generosity. In the modern world we think of chivalry as being romantic; a man who wants to impress a potential wife of girlfriend should respect her, and that respect should remain universal and unwavering, despite the potential difficulties of courtship. This idea of chivalry was formed in the minds and hearts of writers and poets of the Renaissance and Victorian Ages, and unfortunately the real, medieval idea of chivalry is much, much different. The original code of chivalry was masculine. It primarily defined guidelines for the behavior of men of noble birth toward other men of noble birth, basically a bro-code of sorts.

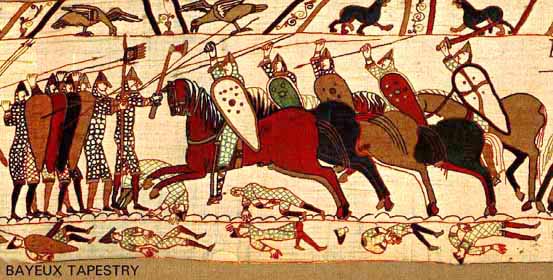

To begin this process of tearing apart any remaining hope some women may still have that men do have it in them somewhere to be compassionate and responsible individuals, let’s start with the roots of the word “chivalry“. The word comes from the French word for knight: “chevalier” or “horseman”. Knights were famous for fighting on horseback. Being on a horse during battle provided a major advantage to the fighter, not just because they were raised higher above the ground, but also because of the sheer force of impact created when you combine horse, rider and lance (the knight’s most infamous weapon). Units of knights, numbering from around twenty up to hundreds of mounted fighters would charge at their opponents with lances pointed ahead, shattering the lines of unmounted infantry coming from the other side of the battlefield.

Detail of the Bayeux Tapestry showing Norman calvery meeting with Anglo Saxon Infantry. The Norman’s use of mounted knights is credited with successful conquest of England. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Author: Dan Koehl

So basically chivalry is supposed to define acceptable behavior for men with horses? It may sound strange… but yes. Back in the Middle Ages most people did not own horses, especially horses bred for war, so only men of high status could afford them. Owning horses is partly what defined a knight and chivalry was the code of honor that these famous horsemen lived by. Being a knight was a high cost, but potentially high reward business. Lord’s wanted knights because they were a valuable asset on the battlefield. In payment of services, knights would be rewarded with money, the title to newly conquered lands, and potentially lucrative marriage opportunities.

Only men of high birth could afford the tools and training it took to be a knight. In those days inheritance was passed down from the father to his eldest son in order to keep the estate intact. Younger sons, even ones born into rich families, were not guaranteed to inherit much. Becoming a knight was a great opportunity for “extra sons” to make a good living. These men were ambitious and had more to gain than they had to loose. One way to strike it rich was through pillaging and ransom, but a knight could go much further if he gained the trust of a prominent nobleman. That’s where the code of chivalry comes in.

Let’s look for the qualities that define chivalrous behavior:

-Courage

-Generosity

-Loyalty

-Trustworthiness

-Prudence

Yes, these are all qualities that most ladies would find desirable in a man, but they are also qualities that a nobleman would find desirable in his trusted circle of loyal servants. In fact, the English work “knight” comes from a Germanic word meaning “boy” or “servant”. Knights are often referred to as “the man” of a certain lord. So knights were high-status servants and in order to maintain their employment they need to be more than just good warriors, they needed to be dependable, trustworthy and courteous. A selfish, vindictive, or rude knight was not a desirable knight, even if he was a great warrior. Knights needed to show themselves worthy of patronage and, in a way, they had to court their nobles like a man might court a woman nowadays.

Since chivalrous behavior was basically a way for ambitious knights to rise through the ranks, guidelines of acceptable behavior according to the code only extended to men of high birth. A knight should avoid killing another knight on the battlefield. It was considered perfectly okay for a knight to capture another knight in battle and hold him prisoner for a substantial ransom, in fact many knights made a living by holding other knights hostage. But even so, while you hold a knight you should treat him well. Some captors did torture and mistreat their noble captives, but those who didn’t gained prestige in the eyes of their fellows. A man who could gain profit or win a dispute with his cunning rather than through bloodshed was considered a desirable knight for a number of reasons, one of which being the fact that alliances often shifted and it was not good business to ruffle the feathers of someone who could someday be a potential ally. However, some people were more valuable than others.

In battle, the infantry was composed a mixed group of commoners and professional soldiers not belonging to the knightly class. Infantry were okay to kill. There was little point in capturing them since you couldn’t ransom them for much, and if you let them go they might end up fighting again in the next force lined up to meet you, so it was best just to get them out of the way. Even innocent civilians were fair game. In the Middle Ages a common military tactic was ravaging: laying waste to your enemy’s land. Crops would be burned, livestock killed, valuables stolen, people murdered. The idea was to starve, terrorize and demoralize the population. By destroying crops and laying waste to towns, there would be nothing for the native army to eat and nowhere for them to take shelter. Some knights made a living by pillaging and many atrocities were carried out far away from the battlefield. It should be noted that Lords were obliged to treat their serf fairly, and rules were set down that specifically detailed how many days of military service a vassal owed to his lord, but the vassals of your enemy were fair game and their was no expectation of a knight’s behavior toward them.

The favor of women was not the primary drive for chivalrous behavior, but it did play a role. In the middle ages, when a noble died with no male heir, his widow or daughter could inherit his property, but they became the ward of the lord of the land, i.e. the king. Kings would reward their most valuable and trustworthy men with marriages to these wealthy heiresses. William Marshal, the most famous of all medieval knights was rewarded for his invaluable services to King Henry II with the opportunity to marry Isabele De Clare, heiress to several estates. Attracting women may have been good for a knight’s ego, it might have gained him prestige among his fellows, but it was not necessary to impress a lady if you wanted to marry her. In fact, it was much more effective to impress her lord, father or brother.

Effigy of William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke, on the south side of the Round Church, Temple Church, Temple, London. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Author: Michel wal.

The favor of a woman could sometimes be valuable for reasons other than an ego boost. In fact, the way that William gained favor with Henry in the first place was through the patronage of Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry’s wife. William came to royal attention when, while escorting Eleanor with his uncle and a large force of other knights, rebels ambushed them. His uncle was killed and William was captured during the attack. But apparently William had distinguished himself during the skirmish because Eleanor paid his ransom herself. After hearing of William’s defense of his wife, along with other stories of Williams’s bravery, Henry II made William the tutor to his son, Henry the younger, and from then on William’s knightly career skyrocketed.

During tournaments, especially the highly structured and elaborate tournaments of the later middle ages) knights would seek the patronage of prominent ladies. Gaining the attention of women both boosted the status of wealthy knights and potentially opened the door for future employment, but the original objective of chivalrous behavior was advancement in society and improving your reputation among other men of prominent standing. Toward the end of the middle ages and in the Renaissance era, the romantic aspect of knighthood began to be emphasized and every man wanted to be a noble, romantic knight who defended his lady. This ideal of chivalrous behavior still persists today. However, this view of chivalry was shaped mainly by fictitious or exaggerated stories of great knights, written long after the events actually took place, during an era in which the world and the ways in which people fought in it was in a process of rapid change.

The modern concept of chivalry is based in nostalgia, the actual roots of the code of chivalry lay in forming relationships between male vassals and their male patrons. Even in William Marshal’s case, The patronage of Eleanor was carried out as any powerful lord, regardless of gender, would reward a servant. Although expectations of behavior between Lords and their vassals did do a lot to cement relationships and provide stability within a a kingdom during the middle ages, and thus did have redeeming qualities, the concept of chivalry as originally formed in the collective mind of Medieval society was far from the norms of behavior we ascribe to the honorable title today. Women in general and anyone from the common classes had little to gain from “chivalrous” behavior.

To learn more about knights and their way of life, be sure to check out our new special exhibition, Knights!