When we survey the field of pre-Contact indigenous cultures in the Americas, the ancient Maya are by far the one we know the most about. Like other cultures, the Maya have left us a very rich archaeological record. We can excavate and investigate their cities; we can be awed by the extensive time depth of their civilization. We can investigate the remnants of their farming efforts and appreciate how the Maya, essentially Stone Age people, significantly modified their environment. Unlike many other cultures, however, the Maya have also left us their voices. Maya writing informs us about their way of life in ways that material culture cannot.

We encounter Maya writing on a broad spectrum of surfaces, including murals, stone, wood, ceramic and shell. Once we read these ancient messages, we realize that some are very esoteric, others refer to politics and belief systems, others yet are very mundane, and some are a bit deceiving.

Among the more mundane examples, there are texts clarifying what a plate was used for (‘to eat tamales”) or who used it (“his cacao cup”). We all can find a certain kinship in this, as we all have mugs in the cupboard sporting similar messages. The plate shown below has all the traits of plates used by the ancient Maya to serve tamales. In this case, however, it is more than just a plate with an everyday message. The actual text portrays a different story (with thanks to Dr. Marc Zender at the Anthropology department, Tulane University).

The text starts with a fairly standard dedicatory sequence. Then it deviates from tradition. Typically, there is a reference to what vessel class we are looking at (which in this case would have been either ‘plate’ or ‘dish’) and a standard context (tamales for this kind of ceramic). None of that is present here. These missing elements, and a somewhat hotchpotch layout, with inconsistent glyph size and spacing, suggest that we are dealing here with a workshop that produced pseudoglyphic texts.

One could suggest that both the owner, or person who commissioned the plate, and his neighbors were not very literate, if at all. This could be a case of “impressing the neighbors,” with neither side being aware that the text made very little sense.

HMNS 2000.1528

Photo courtesy of the Houston Museum of Natural Science

At the other end of that spectrum, and certainly not something one could call mundane, there are texts carved in stone, on monuments archaeologists call altars, that refer to events in a distant past, well before Maya civilization arose. Other texts point out events thousands of years in the future. All brought to our attention courtesy of Maya writing.

Take the carved altar shown below. It was found in the Maya city of Naranjo, Guatemala and dates to 593 A.D. The inscription takes us back to more than 20,000 years ago when a mythical founder of the city was thought to have ascended the throne. Perhaps one can look at this as the Maya version of “a long, long time ago?”

We have all dropped a plate or broken a cup. In some cases, mostly because of sentimental reasons, we decide to hang on to the item and attempt to fix it by gluing the parts together again. Apparently, the ancient Maya shared that sentiment as well, as there is evidence of them trying to repair a broken plate. Instead of using glue, however, they drilled parallel rows of holes through the sherds and then tied them together, as illustrated by the plate shown below.

HMNS 1980.0486

Photo courtesy of the Houston Museum of Natural Science.

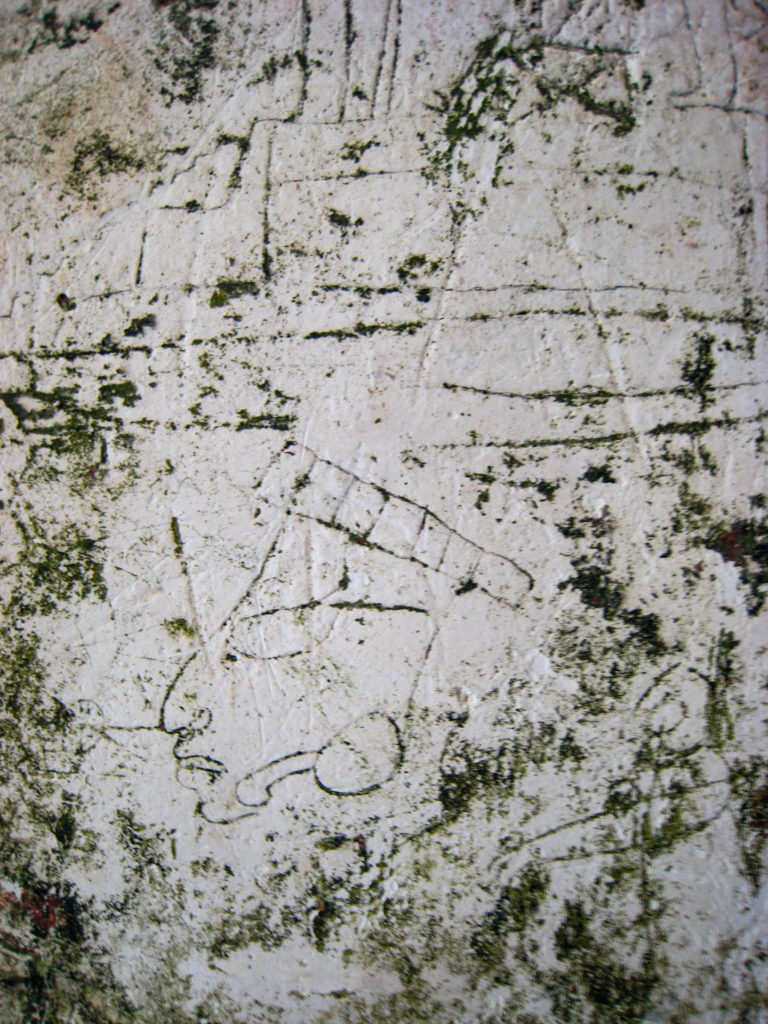

The material record also reveals mischief. Buildings in Maya cities, especially those inhabited by the elite, tended to be covered with thick layers of plaster. Occasionally we find evidence of splashes of color that must have brightened these spaces. Much to our delight, we also find graffiti. In some cases, these lines scratched into the plaster show us what the “artist” may have observed: a parade on the central square of their city showing a ruler being carried around in a sedan chair. We see banners being carried aloft, representations of pyramids with superstructures now long gone. Occasionally we even see images of executions, all part of life in a big Maya city, but always represented in an informal way. In some cases, by looking at the elevation of these graffiti above the floor level, archaeologists have surmised that the artists were children. Fair to say, that will sound familiar to most parents.

Tikal, Guatemala

Image by Russell Harrison, CC BY-SA 3.0

Maya rulers loved to see themselves represented and commemorated in stone monuments, like stelae and lintels. These carry not only royal imagery, but also show the finery in which these lofty individuals paraded around: beautiful, colorful textiles, heavy jade necklaces and elaborately carved flint royal scepters. The accompanying texts shed light on Maya political organization, identifying city names, perhaps even the royal realm beyond the city, as well as the layering of the political class. The glyphs carved in the lower, right hand corner of the lintel shown below references the artist(s) who carved the monument. Being literate was deeply appreciated by the ancient Maya, clearly it was a skill worthy of being commemorated in perpetuity.

Museo Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Guatemala

Photo by Dirk Van Tuerenhout

Mural paintings often show us a similar dazzling array of clothing, ritual, while the accompanying texts identify who is shown or what is being done. Sometimes we also see what is absent: cartoon cartouche-like empty spaces, ready to be filled in with text that has remained empty. Evidence of work left unfinished.

All of these examples help explain why the ancient Maya are a bit better understood than other pre-Contact cultures. It always makes us want to know more. Our soon to be renovated John P. McGovern Hall of the Americas will present this story both in text and in three-dimensional context. Keep your eyes peeled for more news.

With great thanks to Dr. Marc Zender, Anthropology department, Tulane University, for his insights in and translation of the text that appears on the tamale plate.

Your contribution matters today more than ever, as we strive to ensure that the museum is ready and able to welcome you back. Please GIVE TODAY to help support our mission of science education.