We’ve all heard of the notorious classified ads. Whether you think the stories emanating from those newspaper columns are romantic or creepy, it can’t be denied that they are interesting to hear about. Here at HMNS we have missed connections everywhere. But I don’t mean human connections, or a least living human connections…

The connections that will be discussed in our new series Missed Connections are between artifacts in our various collections. We will discuss connections between our Hall of Gems and Minerals and our Hall of Ancient Egypt, between our Hall of Paleontology and our Hall of the Americas, and many more; connections that the average patron visiting our halls may never suspect. Some of them may sound far fetched, but the Earth is a small place and everything that rests on the limited reaches of its surface are bound to be intimately connected in one way or another. This week we will discuss the malachite in our Hall of Gems and Minerals and its connections to ancient Egyptian culture.

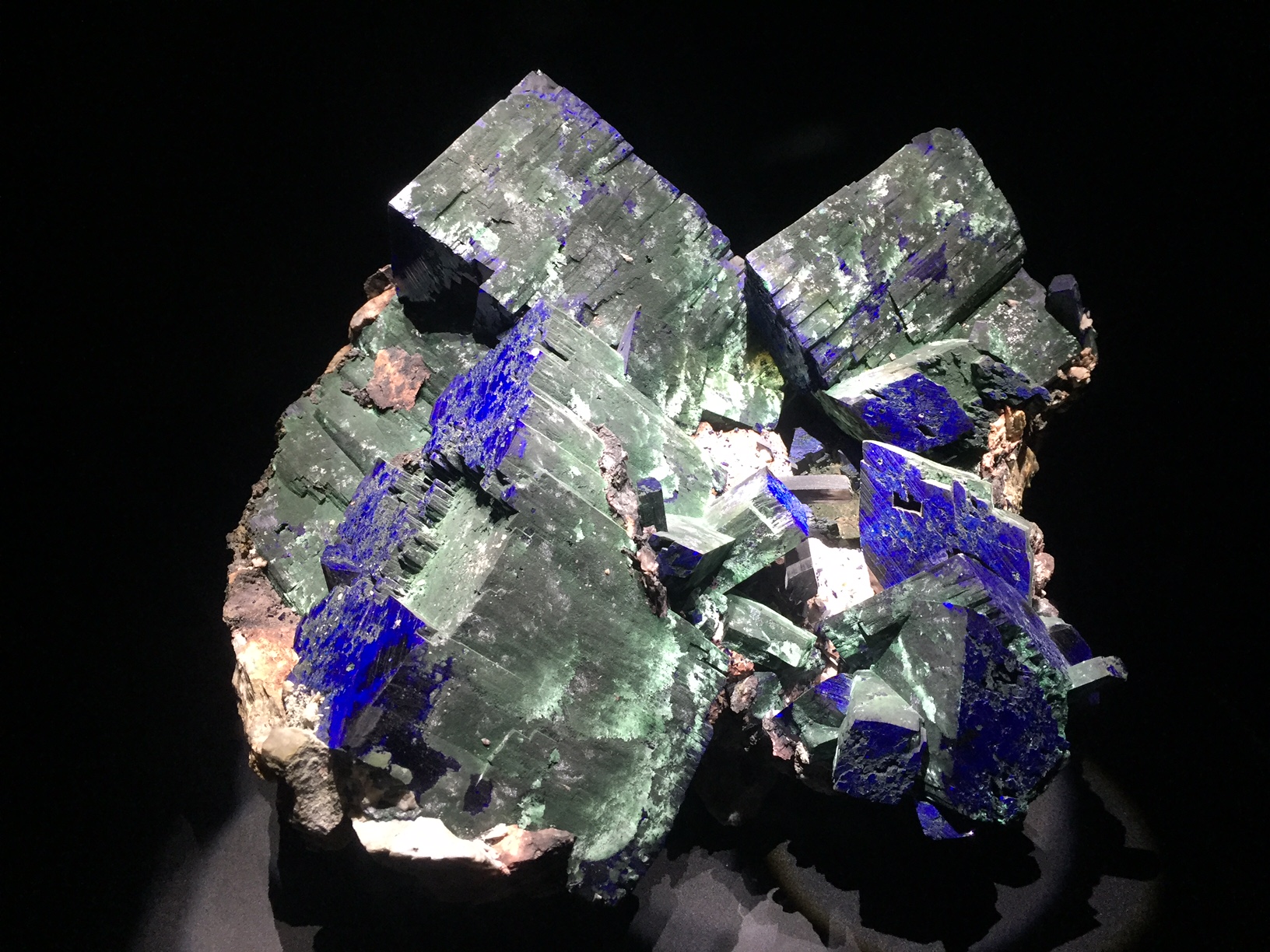

Malachite ( Cu2(CO3)(OH)2 ) is a copper ore found all over the world. It is formed by a chemical reaction between weathering copper deposits and carbonates in the surrounding rock. It usually occurs in limestone, in the shallow layers above underground copper deposits. It has a hardness of 3.4-4 on the Mohs hardness scale, which makes it ideal for carving. It was first exploited in Egypt and Israel over 4,000 years ago. It is often found with azurite ( Cu3(CO3)2(OH) ), as the piece from our Hall Gems and Minerals pictured above is.

There is A LOT of malachite used in the artifacts on display in our Hall of Ancient Egypt, but not in the way you would expect. There are no carved beads or statues of the material, as you will often find today in mineral shops or jewelry stores. Instead, the mineral was ground up and used as a pigment for all kinds of purposes. The most interesting of which is cosmetic.

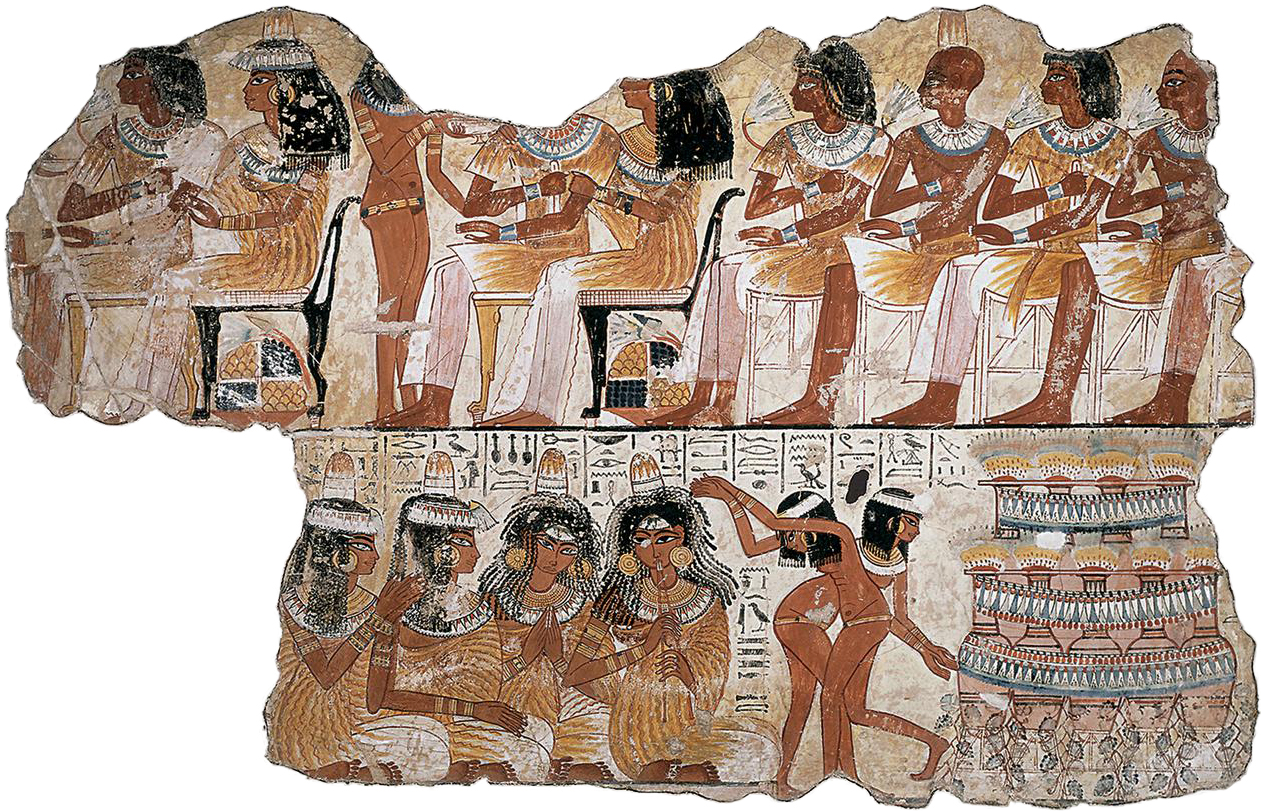

Above is an image of King Mentuhotep II, who reigned around 2,000 BCE during the Egyptian Middle Kingdom (so long ago that it predates the title “pharaoh” by centuries). The image above is from his tomb near the Valley of the Kings. Now look closely into his eye: it’s beautifully carved and surrounded by a pale, greenish-blue pigment. That pigment is most likely made of malachite. Malachite was used in the elaborate cosmetic designs that high ranking Egyptians would paint around their eyes to distinguish themselves and mimic their falcon-headed god, Horus. Most people imagine Egyptian eye-liner to be black and that’s not wrong but green was commonly used as well.

The color green had powerful symbolism to the Ancient Egyptians. Above is the malachite-green painted face of one of the wooden coffins in our collection. To modern museum visitors, the green faces on our coffins have negative connotations: think Frankenstein’s monster, zombies and witches. Since mummies have entered the modern pantheon of ghouls and ghosts, it seems natural for yucky, decaying flesh to be portrayed on their coffins. But in reality the Ancient Egyptians associated green with life.

The green faces on our coffins are inspired by the story of Osiris, the Egyptian god of plant life and the king of the underworld. As the story goes, Osiris is a benevolent king who is murdered by his jealous brother, Seth. Seth chops Osiris’ body into pieces and scatters them all over Egypt so that Osiris can never return from the dead. Luckily, Osiris’ wife, Isis, loves her husband very much and journeys all over to find the pieces of his body. She puts him back together and uses a spell she receives from Toth, the god of scribes, to resurrect him. Afterwards, Osiris journeys to the underworld and becomes king of the afterlife. He is also considered the god of plant life because like plants during the rainy season, he too was reborn.

In painted images found on walls and in papyrus scrolls, Osiris is shown as a green man; green like the vegetation that is resurrected every season. But he is not the only god that has an association with malachite. The statues above (except for number 2) are made of faience colored with green malachite. Faience is sometimes called the plastic of ancient Egypt; it is a hard, glassy substance made of quartz sand, pigments and binders that are heated until they solidify into a brightly colored solid.

The examples above are finely made and would have belonged to elite Egyptians but there is an abundance of cheaply made Faience pieces made to cater to the lower classes. Everything from religious statues like the ones shown above to jewelry like the necklace pictured below was made of malachite-colored faience. Faience was a cheap alternative to the rare and extremely difficult to carve gemstones used in the finest jewelry and sculpture.

Today most of us associate malachite with cheap gift-shop bead necklaces and bracelets, but the mineral has a long and varied history. To past cultures, the green mineral has had important royal, spiritual and religious connections; connections that many visitors to HMNS may have missed.

If you want to see these amazing objects for yourself, come to HMNS and visit our Permanent Exhibit Halls. $25 for adults and $15 for kids will get you into 11 exhibits filled with amazing artifacts and dazzling displays designed to entertain and inform.