I recently had the opportunity to travel to Philadelphia. Everyone else was hot and bothered to see the birthplace of American democracy. I was excited to see the science museums: The Franklin Institute, The Academy of Natural Science, The Mutter and Independence Hall. (You read right on that last one. Keep going…)

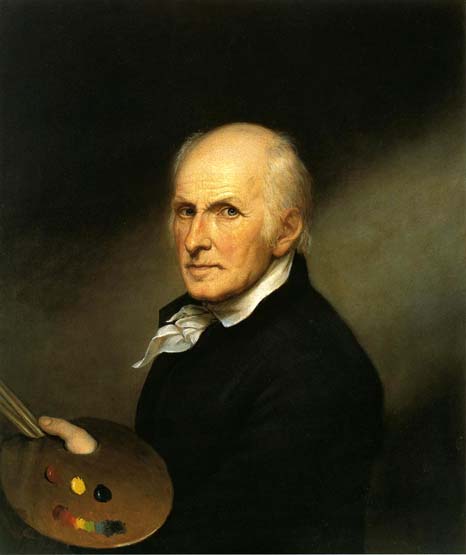

Next month, April 29 to be exact, we are opening a Wunderkabinet – a Cabinet of Curiosities. Our curiosities will be styled after those of Ferrante Imperato, an Italian apothecary who created, arguably, the most famous cabinet of curiosity in the world. But today you’ll be learning about Charles Wilson Peale’s cabinet of curiosities. Because he is super awesome.

I’m not going to go into his backstory here, because it’s just too long, bizarre, and interesting on its own. I’m not going to talk about how he organized the first U.S. Scientific expedition in 1801 or how he went a-courting at the age of 88 or how they had to shoot the bear because it kept eating the rest of his collection. I will save that for another blog. (Honestly, it will probably be a couple of blog entries because I think Peale is super dreamy). Instead, today we are talking about Peale’s “Repository for Natural Curiosities,” his Philadelphia Museum.

I started my Peale sightings that day in Philadelphia at his grave, and all day long virtually every person I asked was very confused about why I cared about Peale, or they had no clue who he was. Half my morning was spent extolling the virtues of this wonderful American painter, scientist, statesman, entrepreneur and patriot. It was at the point when I had a crossing guard helping me look for a historical marker that I realized I had reached new heights of nerddom. Oh Peale, you make my heart flutter.

Here’s the short(est possible) version of this tale. In 1786, Peale opened America’s first natural science museum to the public. It was known as the Philadelphia Museum, or colloquially as “Peale’s American Museum,” and was similar to that of Ferrante Imperato, in spirit. Peale was inquisitive himself and eager to instill that quality in others. Peale designed his museum to inspire a curiosity of the natural world and educate patrons about the diversity of life.

So what does all this have to do with Independence Hall? Peale’s Museum started out as a small collection of portraits that he called “The Gallery of Great Men.” This gallery contained portraits of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Benjamin Franklin and many others, but it grew to include specimens when he had the opportunity to sketch a collection of mammoth bones. The bones drew a crowd and Peale recognized an opportunity when he saw one. He began collecting specimens and added them to his portrait gallery.

Over the years, as he grew out of one space, he’d move to another. This led him to rent spaces in two very prominent buildings in Philadelphia. The first place you might know is a small building next to Independence Hall, where he rented a small gallery. This is the current location of the American Philosophical Society, which Benjamin Franklin founded and of which Peale was a member. The second was the Pennsylvania State House, more commonly known now by its nickname, “Independence Hall.” It was officially named the Philadelphia Museum, but referred to as “Peale’s Museum.”

Peale created the first scientifically-organized museum of natural history in America. Museums didn’t really exist in Peale’s time and those that did weren’t public. Peale’s museum was open to anyone with a sense of wonder and 25 cents. The “Great School of Nature” is what Peale called it. Although you may not know his name, Peale was a peer of America’s greatest men. Franklin regularly corresponded with Peale and donated to Peale the corpse of his French angora cat to be put on display. Washington contributed a pair of golden pheasants. After the Lewis and Clark expedition, President Jefferson, a close friend of Peale’s, arranged for specimens to go to Peale.

When I arrived at Independence Hall that morning, I was warmly received by Jane, a National Park Ranger, who assured me that I wasn’t doing American history wrong. I was apparently the only person ever to forgo the tour of the room in which the Declaration of Independence was signed in favor of seeing the rooms in which Peale housed his museum.

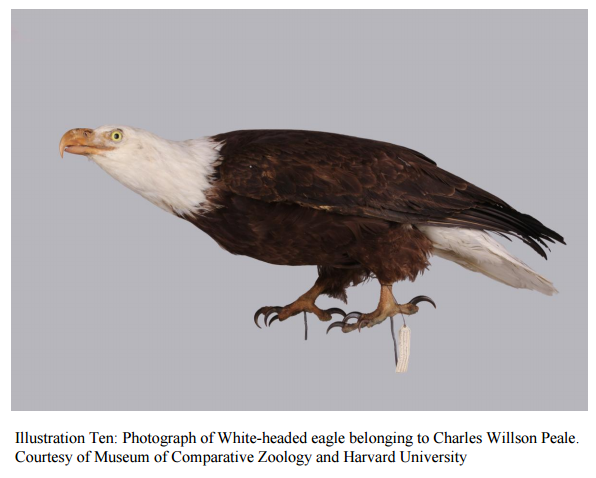

Peale’s collection housed both local species, that the entire Peale family collected, as well as exotic items from abroad. Sea captains brought him a llama, an antelope, an ape, and monkeys — all kept outside until they died and were then preserved. The family also had a bald eagle who imprinted on Peale and lived atop Independence Hall.

One of Peale’s biggest struggles was discovering the secret to preserving these specimens when they died. After much experimentation, he settled on an arsenic solution for the birds and smaller animals and bichloride of mercury for the larger specimens. It worked, but was extremely toxic. Peale believed the purpose of his museum was “to bring into view a world in miniature.” To do this, Peale used his artistic abilities to make the displays visually appealing. It was not just a bird in a case; his displays included painted landscapes with real branches and rocks. Peale’s innovative habitats would become the standard for museum practices in modern museums.

In 1791, shortly after the death of his first wife, Peale found a new wife in a group who had come to visit the museum and a few weeks later they married. She inherited six boisterous children (by the day’s standard), a menagerie of wild animals and constant visitors to the museum. The kitchen, usually considered the woman’s domain at the time, doubled as a laboratory and taxidermy shop. The Peale family unanimously loved her.

Peale accepted an offer from American Philosophical Society in 1794 to move the museum and his family into the Philosophical Hall. At this time, he switched his focus more wholly to science over art. Peale was the first to use Linnaean taxonomy in organizing a collection, whereas other Museums just presented a Wunderkabinet — a smattering of specimens. Also in 1794, he had a little boy whom he named Charles Linnaeus. In 1795, another son arrived and it was the members of the Philosophical Society that named him Franklin, by a majority vote, after their founder who died in 1790.

In 1802, Peale asked Thomas Jefferson to establish a national museum 50 years before the inception of the Smithsonian. Jefferson agreed that this was an excellent idea, but couldn’t agree to give public government funds for the project. So Peale asked the Pennsylvania State Legislature to support his ever-growing collection. They agreed to let him use the upper floors of the main building, the tower and first floor east room in the Pennsylvania State House, now Independence Hall, except on Election Day, when they would need to let people come in to vote.

When the new and improved museum opened to the public, it contained 4,000 insects, a large mineral collection, a grizzly bear, a buffalo, a hyena, an antelope and a llama. It also contained a lens focused in on the venom groove in a snake’s fangs and artifacts from Native American tribes, Polynesia and the Far East. It also housed machines, antiques, inventions and copies of famous statues. To liven things up, the Peale family also did live snake handling demonstrations and procured an organ for evening recitals.

The first three people to have a membership to the museum were George Washington, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson — the acting President, Vice President and Secretary of State for the newly-formed United States of America. In fact, George Washington headed the annual membership drive.

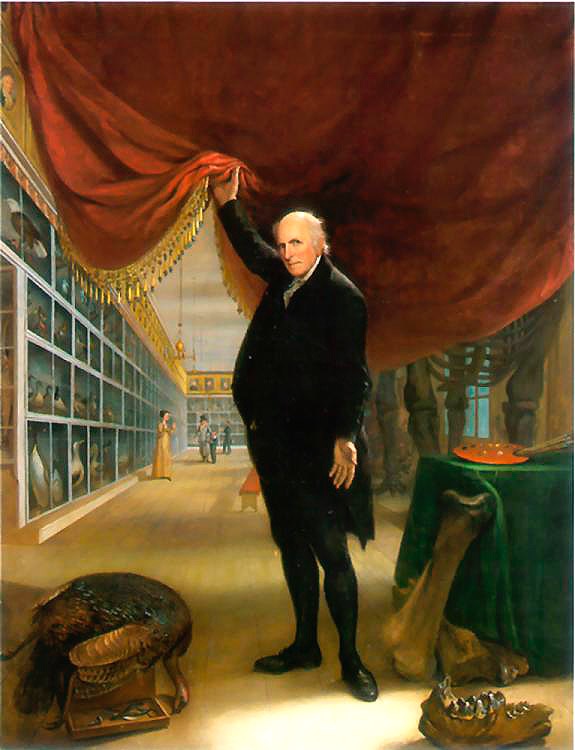

At the age of 81 and at the request of the museum’s board, Peale painted one of his most well-known pieces of art, “The Artist and his Museum,” which is an amazing peek into the last version of Peale’s American Museum.

During his life, Peale never saw the establishment of a National History Museum and 20 years after his death, his collection was dispersed. Some of the scientific specimens were sold to P. T. Barnum and some were destroyed by a fire. “The Gallery of Great Men” was bought in bulk by the City of Philadelphia and is now on display in the Independence Hall National Historic Park Collection — just as Peale wished.

Author’s Note: A big thank you to Park Ranger Jane who provided me with some pretty useful information and was willing to tolerate my unbridled enthusiasm!

Author’s Note: A big thank you to Park Ranger Jane who provided me with some pretty useful information and was willing to tolerate my unbridled enthusiasm!