On December 21, 2020, the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn appear only one tenth of one degree apart in our sky. They have not appeared that close since July 10, 1623. Of course, Jupiter is not really next to Saturn. Saturn is in fact about 4.3 astronomical units (AU)–about 400 million miles–behind Jupiter. (One AU is the average Earth-Sun distance.) However, Saturn is pretty much right behind Jupiter; the two planets are along almost the exact same line of sight. That’s why we’ll see them almost touching on December 21.

This happens because the closer a planet is to the Sun, the more gravity it experiences and the faster it orbits. Jupiter is 5.2 AU from the Sun and takes 12 years to orbit. Saturn, at 9.5 AU from the Sun, takes 29.5 years to complete one orbit. About every 20 years, Jupiter, on its faster orbit, overtakes Saturn. So every 20 years or so, we see a Jupiter/Saturn conjunction in the sky.

But most of these conjunctions are not this close. That’s because the planets are almost, but not exactly, in the same plane. Jupiter is inclined by 1.3 degrees from Earth’s orbital plane (the ecliptic), while Saturn is inclined 2.48 degrees. Those inclinations are small (90 degrees would mean an orbit perpendicular to Earth’s), but enough to mean these two planets almost never appear within 0.1 degrees of one another, even when perfectly aligned.

Another question is, ‘Where is Earth when Jupiter laps Saturn?’ If Earth is on the same side of the Sun as those gas giants when they pass each other, we see not one but three conjunctions. Although Jupiter laps Saturn only once each time, the faster motion of Earth makes the planets seem to move backwards (retrograde) for a while, causing a second conjunction. As Earth pulls far ahead, we see the planets’ normal motion, resulting in a third conjunction. This happened in 1980, although that time Jupiter never appeared as close to Saturn as it does this year. On the other hand, Earth might be on the opposite side of the Sun when Jupiter aligns with Saturn. This would make the conjunction invisible to us, as the Sun would be in the way. This is what happened in 2000, and also back in 1623, the last time Jupiter passed this close to Saturn. Virtually no one saw the last conjunction like this one. The most recent Jupiter/Saturn conjunction which was this close and visible in a dark sky was back on March 5, 1226.

That this happens close to Christmas adds a new wrinkle to the story. One theory for what the Christmas Star might have been is in fact a Jupiter/Saturn conjunction. In 7 BC, Jupiter lapped Saturn while Earth was on that same side of the Sun, causing a triple conjunction (like in 1980). Astrologers such as the Magi might have taken that as an omen. Also, the conjunction would have shifted from west to east over the many months of a journey from the Magi’s home to Israel. We detail this in our planetarium’s ‘Mystery of the Christmas Star’ show. Of course, we must consider that miraculous events in holy stories may not correspond to anything in nature.

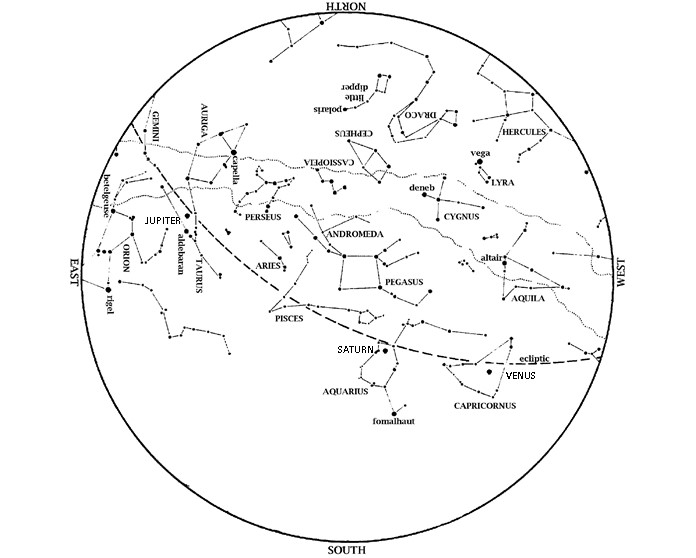

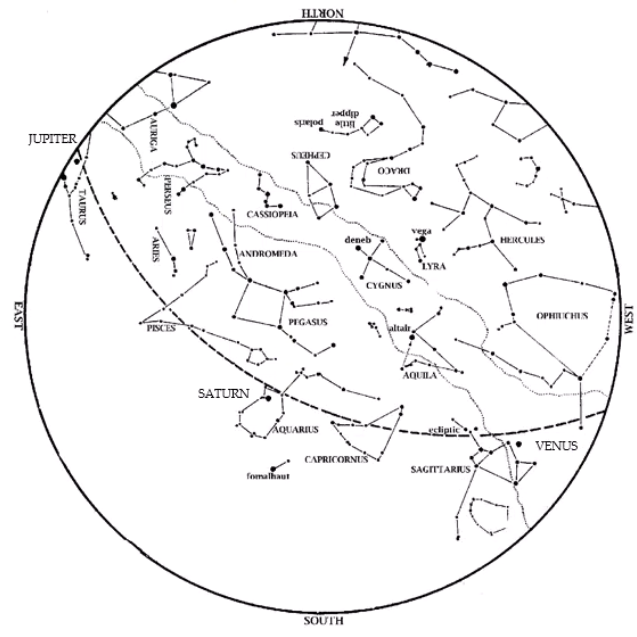

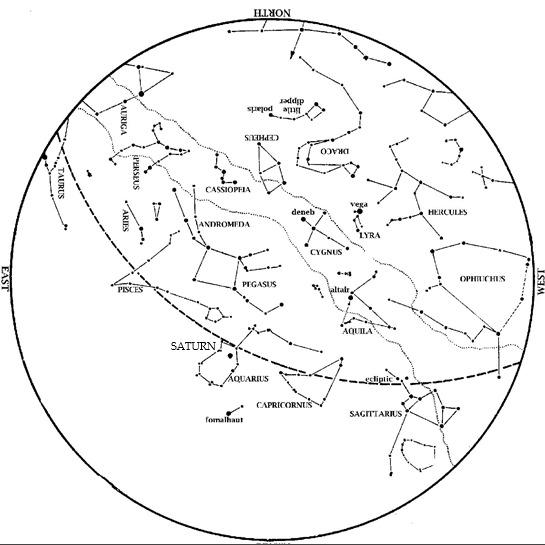

To see Jupiter and Saturn this month, go outside right at nightfall and face a bit to the left of where the Sun went down. Don’t wait too late; these planets set by 7:40 and thus go behind trees or buildings around you much before that. No star at night is ever as bright as Jupiter, so you’ll have no trouble seeing them even from your backyard in Houston (or other big city). Just look for the brightest thing in the area (Jupiter) with Saturn as a dimmer dot right next to it. The conjunction is closest on December 21, but is still very close for a few days before and after.

Jupiter won’t appear this close to Saturn again until March 15, 2080. And observers will have to get up early in the morning to watch that conjunction 60 years from now.