Written in 1794, William Blake’s poem “The Tyger” remarks on the ferocity of this large Felid. When my museum colleagues asked me to hammer out this piece, the first thing that ran through my mind was rejoicing at the opportunity to misspell the name of the tiger (Panthera tigris), as Blake did in what is often considered the most anthologized of English poems.

While I have worked with the Latin American Tigre (the common name for the Jaguar [P. onca] in Latin America), I have not worked with tigers in their native range. So why would HMNS be interested in having me provide a blog on tigers? Tiger King of course. Unfortunately my family is not quite hip enough to subscribe to Netflix, but I have heard a LOT about this show from friends and family.

While the interactions between tigers and humans on Netflix are entertaining, one of the most fascinating true stories I know regarding interactions between tigers and humans involves man-eating tigers of Sunderbans, India. A recurring problem with all large cats is that older or sick individuals may not have the stamina or strength to hunt animal prey, so will sometimes resort to hunting humans and livestock (easy prey). In eastern India near the border of Bangladesh, the coastal Sundarbans region is well known for the fishermen who live there. When the population of tigers there turned maneaters, preferring the flesh of humans to that of wild prey, the tigers discovered that fishermen could be easily taken when they were squatting at the riverbank to untie their boats to go fishing. When they were squatting down preoccupied is when the tigers would strike from behind. How did the people of Sunderbans solve this problem? By wearing masks on the backs of their heads! Tigers would only attack if the fishermen weren’t facing them, so the mask on the back of the head fooled the tigers enough to thwart attack.

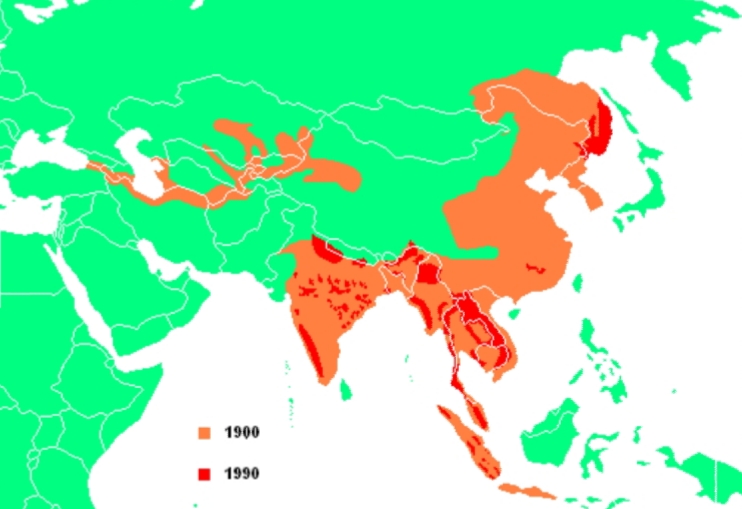

Many people don’t even realize there are several subspecies (races) of tigers that vary geographically. These range from the huge Amurian or Siberian tiger (P. t. altaica), which can reach lengths of nine feet and tip the scales up to 700 pounds, to the much smaller Bali tiger (P. t. balica), perhaps half that mass. The other big difference is extant vs. extinct – the Siberian tiger is still with us today, whereas the smaller tiger from the island of Bali went extinct around 1937. Other races of tiger that are extinct today include the Caspian tiger (P. t. virgata, extinct 1970), Javan tiger (P. t. sondaica, extinct 1980s), and in all likelihood the South China tiger (P. t. amoyensis) which has not been seen since the 1970s.

The race of tiger that is the best known, often as a mascot, featured in Tiger King, and the Tyger in Blake’s famous poem is the Bengal tiger (P. t. tigris) from India. This is also the most abundant races, with 2000 optimistically remaining in nature. Other races that are still extant include the Northern Indochinese or Vietnamese tiger (P. t. corbetti), Malayan (P. t. jacksoni) and Sumatran (P. t. sumatrae) tigers. Only a few hundred each survive in nature for both Siberian and Sumatran tigers, and Malayan tigers are even scarcer with perhaps half that number remaining.

The primary threats that tigers face today are the same as most species —hunting, poaching and habitat loss. Since they are top predators, maintaining the integrity of an ecosystem by keeping herbivores in check, their prey base is also disappearing with habitat clearance, meaning that starvation is also a very real threat. Traditional Chinese medicine also places demands on powdered tiger bones, paws, whiskers and other body parts. Tiger farms in Southeast Asia, while ethically questionable, help reduce tiger poaching from populations in nature, thus offsetting the demand through captive sources.

We are fortunate to live in times of tigers, elephants, whales and other mega-vertebrates. Future generations might not be so lucky. If you can, and once we’re all able to travel again, take a trip to Big Bend, Yellowstone, Alaska or even overseas to Africa or India. What you witness will provide memories for a lifetime.

Until then, stay safe and wash your hands!