Walking into the Cockrell Butterfly Center (CBC), one of the first things you’re likely to notice is the sound of a 50-foot waterfall. The conservatory’s high glass ceiling, forest of lush plants and thousands of fluttering butterflies couldn’t be further removed from the sterile, white walls of a science lab. But just beneath the tropical veneer, science is literally buzzing.

Using Nature to Fight Nature

During the spring and early summer of 2019, the scientific endeavors of the center expanded as scientists from Harris County Precinct 4’s Biological Control Initiative conducted biocontrol experiments in our rainforest. Let’s break that down. Harris County is covered by four precincts that handle a lot of the bureaucratic odds and ends that seem ubiquitous to many of our daily lives—maintaining roads and parks, improving flood prevention, etc. A primary effort in a flood-prone, bayou setting like Houston is the control of mosquitoes, and Precinct 4 uses a combination of organic and inorganic methods to control pests, including their Biological Control Initiative.

But first, what is biocontrol? Generally, biological pest control is the method of controlling pest populations through the careful and intentional management of predators, parasites or even pathogens of the unwanted animals. Our butterfly center already uses some biocontrol measures in the conservatory. “For almost any pest insect, there’s going to be a parasite, fungus or predator that can take care of it for you.” Erin Mills, Director of the Cockrell Butterfly Center, explains. “We employ an army of biological control agents in there—ladybugs, lacewings, beneficial nematodes—all sorts of things.” The primary targets of the precinct’s biocontrol program are the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) and yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti).

If you live in or around Houston, you’ve swatted away these insects while relaxing on your back patio in the hot, summer evenings. Imported as stowaways a couple hundred years back in merchant marine vessels’ drinking water containers and also, more recently, in tires traveling from the tropics of Southeast Asia to the U.S., these black-and-white striped bugs are invasive species and often carriers of Zika virus, West Nile virus, Chikungunya and dengue fever. The females require a protein-rich blood meal in order to lay eggs and will feed on humans and animals before depositing her eggs in stagnant water. This bite is the vector through which these deadly diseases are spread.

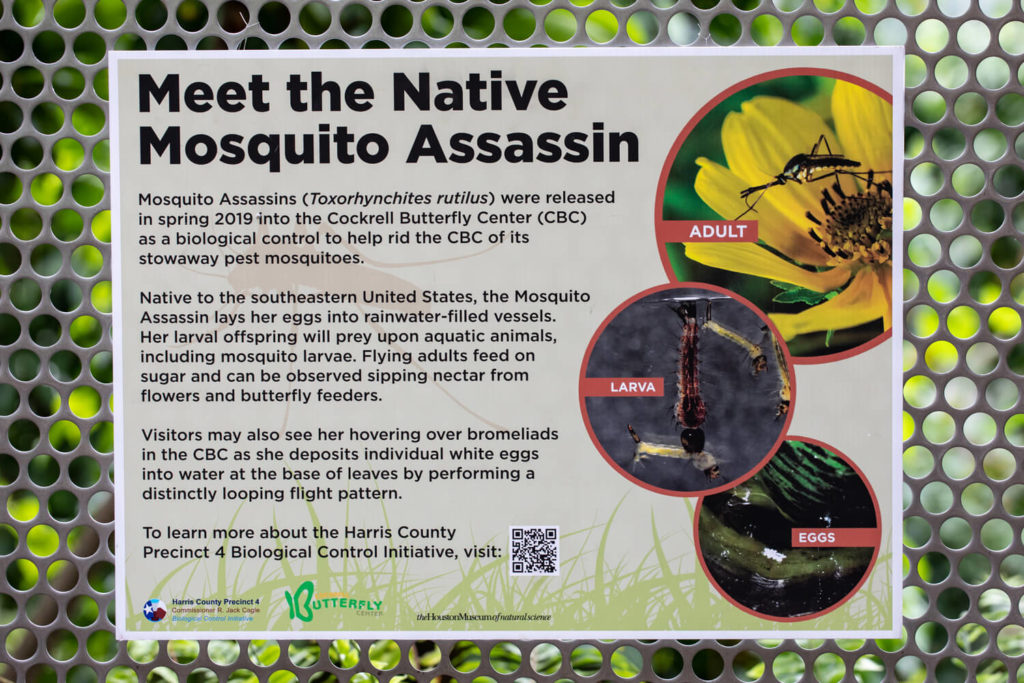

The Precinct 4 research team uses a combination of biocontrol agents (natural enemies of the Asian tiger and yellow fever mosquitoes) that they’ve lovingly dubbed “Schiller’s killers” after their director and head researcher Anita Schiller. Toxorhyncites rutilus, also known as the mosquito assassin or the elephant mosquito, is the core focus of the research going on in our conservatory. “The Cockrell Butterfly Center is the perfect environment for a semi-controlled study. Animals can’t enter or leave without permission, so to speak, so whatever we place into the CBC stays there, and we can track the numbers really well,” Schiller explains.

Schiller and Mills knew one another through their work in the entomology field, and when Schiller approached Mills about using our conservatory for a semi-controlled study, she was immediately a strong supporter. “A self-sustaining population of mosquito assassins in the butterfly center will not only help control our mosquito population but it will also spread mosquito assassin awareness,” Mills said.

The Hippies of the Bug World

So, how do mosquito assassins control Asian tiger mosquito populations? The mosquito assassin shares the same family as its pest counterpart, but there are some distinct differences between the species. Mosquito assassins are distinguishable from the Aedes mosquitoes aesthetically; they’re larger and have iridescent blue, purple and green scales. Their mouthpart (the proboscis) is bent, facilitating floral nectar sipping while being incapable of biting. As adults, they feed on plant nectar and act as pollinators, but it’s their larval stage that separates them the most from their invasive, distant cousins.

Female mosquito assassins also lay their eggs in temporary rainwater-filled vessels and vertebrate predator-free waters, where they are carnivorous and eat anything swimming alongside them, often other larvae. This natal consumption of protein gives female mosquito assassins the nutrients they need to successfully lay eggs later in life, so reproduction doesn’t require them to feed on blood as adults. The same mechanism that makes them excellent predators of the Aedes mosquitoes causes them to not act as pests and vectors of disease for humans. In the words of Precinct 4 Commissioner R. Jack Cagle, “It’s a win-win.”

“I call them [mosquito assassins] the hippies of the bug world…” said Cagle, “They fly around from flower to flower, pollinating them, allowing us to have better vegetables, and they’re sparkly. They make love and lay eggs, and that’s all they do as adults.”

One of Schiller’s research assistants Atom Rosales also spoke to the mosquito assassin’s gentle nature. “They’re pretty docile creatures,” Rosales explained. “They like to hover over the bromeliads in the center, and they love the color blue.” He indicated his own blue precinct uniform, “so sometimes, they’ll just hang out on us while we conduct our research.” The violent name— mosquito assassin—turns out to be quite the misnomer.

If biocontrol seems too good to be true, that is sometimes the case. A common example is the cane toad. Introduced to Australia, these poisonous amphibians were part of an attempt to combat populations of cane beetles that were ravaging sugar cane crops. Not only did the toads do little to eradicate the beetles, they became pests themselves, having no predators who could consume them because of the toxins they secrete from glands in their shoulders. That’s a worst case scenario, and Schiller reminded us that, “in this situation, the Asian tiger mosquitoes are the cane toads.” Meanwhile, native mosquito assassins already populate wooded areas around Houston. Increasing their numbers through the program simply aims to augment the existing population’s ability to prey on the invasive intruders.

A Living Lab

The research in the butterfly center is a part of a semi-controlled study that determines the efficacy of mosquito assassins as biocontrol agents and has two key goals: 1. Eliminate the small population of Asian tiger mosquitoes in the CBC. 2. Establish a self-sustaining population of mosquito assassins in the center. Other goals, like education of the public, are accomplished through signage in the center, and you reading this blog right now.

at the Cockrell Butterfly Center.

For four to six weeks, Schiller and some members of her team ventured in the Cockrell Butterfly Center every Tuesday morning. Depending on their tasks for the day, they stayed anywhere from two to six hours in our living lab. Each week, the team transported approximately 100 gravid mosquito assassins reared from their offsite lab. Then, the team would collect data by checking various egg traps around the center and counting the numbers of Asian tiger mosquitoes and mosquito assassins in them.

When asked about the nature of the data collection, Schiller just laughed, “Yeah, you better like counting. We do a lot of it.” Releasing the female mosquito assassins from their mesh transport cages was one of the last tasks of each study day. Water samples were also acquired for chemical testing back at their lab. The data gives the research team a ratio of insects, allowing them to make calculations to determine the overall population living in the entire center. Those calculations continued for several weeks after releases of the assassins ended.

Harnessing the Mosquito Assassin

The work done in the Cockrell Butterfly Center is only part of the entire scientific process. Schiller has a lab and research team in Spring working on rearing mosquito assassins en masse. “One of the biggest challenges,” Schiller explains “is rearing populations of mosquito assassins large enough to maintain a steady release schedule.” Right now, Schiller’s team is one of the closest to accomplishing that. They’ve constructed holding cages for every stage in the mosquito assassin life cycle. Stacks of trays line the walls and hold eggs and larvae before they mature to the adult stage, where they’re transferred to new holdings to mate and produce enough gravid females for release.

When the project began, the only instructions available for adult enclosures were that they had to be “large” to encourage reproduction. “In science, large is relative. We had to try different sizes to figure out what large even meant,” Schiller recounted. By November of 2018, 85,955 eggs were being produced in one month, and the team is closer than ever to creating assassin release kits, or Aedes Predator Pods (APP), to tackle backyard mosquito problems.

Previous field studies conducted by other scientists in Louisiana revealed that the release of mosquito assassins following ultra-low volume insecticide application reduced the target population by 98 percent, whereas insecticide application by itself provided only a 29 percent reduction. The results from this semi-controlled study will add to the breadth of knowledge about this type of biocontrol.

“We’re really good at what we do,” Schiller proudly beamed at her team as she showed us around her lab. “We’re passionate.” But that goes without saying. The care with which she leads her team and pursues environmentally friendly solutions to pest control is evident. She knows the importance of her work to help lower the amount of pesticides that are used to control mosquitoes in a mosquito-rich setting like Houston. It makes the environment and all of us healthier and happier. Commissioner Cagle put it this way, “when we work with nature, we enrich ourselves.”

Learn even more about this project at a distinguished lecture featuring Anita Schiller. Find out more about the Mosquito Assassins’ unique biology and the role it plays inside the tropical, butterfly-filled landscape of the Cockrell Butterfly Center and how a local program aims to incorporate their use in the fight against Harris County’s omnipresent pestiferous backyard mosquitoes. Get tickets here, and visit our site to browse our large selection of adult education opportunities—lectures, classes, behind-the-scenes tours and more!