It’s National Camera Day, which is a particularly relevant holiday to our institution since we just opened our new special exhibition In Focus, which is basically an immersive art space where you can go and take really cool pictures of yourself and your friends.

Seeing all the visitors who have come to the exhibit to have fun with photography over the past few weeks has got me to thinking about how fundamentally important photography is to human history. Photography has given common people the ability to be remembered. It’s also opened a window onto more recent eras of history that allow us the better empathize with those who came before us. Even for ancient history, the movie industry has done a lot to increase the general public’s familiarity with societies that existed in the distant past.

You may not know it, but your pics are probably the longest-lasting thing you’ll leave behind for posterity. There will be a time when all anyone really knows about you is what they can glean from your pictures. Sure there will probably be tax documents and other public records, but nobody wants to read that stuff, except maybe professional historians. Your social media posts may also last, but much like the cool digitized copies of old local newspapers preserved at libraries today, most people in the future may not be all that curious to look through those. It’s probably for the best anyway…

A picture says a thousand words, and people feel a closer connection to events and historical figures that they can actually see. So images are the most accessible form of recorded history,

If you were born more than a 150 years ago and you were’t exceptionally wealthy, pretty much the only way to be remembered was to either carve your name into an important monument or do something incredibly noteworthy.

Lucius Trebonius Oricula and Gaius Numonius Vala made it into the history books using the former method. The two carved the following inscription (originally in Latin) on the South Pylon at the Temple of Isis in Philae, Egypt circa 2 BCE:

“I, Lucius Trebonius Oricula, was here. I, Gaius Numonius Vala, was here in the thirteenth consulship of the emperor Caesar, eight days before the Calends of April.”

While we’re talking about graffiti, the oldest known image of Jesus is a mocking image depicting a donkey-headed man on a cross carved into a wall in Rome dating to the 1st century BCE.

Another interesting incident related to preserving one’s memory was when Herostratus burned down the Temple of Artemis, one of the 7 Wonders of the Ancient Word, so that he would be remembered by history.

Being remembered was a dicey game in those days. It worked out pretty well for Lucius and Gaius, but Herostratus was tortured to death for his trouble and Jesus was lucky to have had a much better record of his actions than the graffiti mentioned previously preserved for his posterity. Most commons folks played it safe and resigned themselves to fading into obscurity after their death.

View from the Window at Le Gras, 1826–27 (manually enhanced version). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

That all changed with the advent of photography. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce took the earliest known photograph in 1826 or 1827. His medium was light-sensitive bitumen dissolved in lavender oil and applied to the surface of a flat sheet of pewter. The exposure time was around 8 hours, not so great for capturing people, but he did manage to get a nice picture of some of the buildings on his estate. To think that this image was produced only about a year after Thomas Jefferson and John Adams died shows how tantalizingly close we were to actually seeing some of our country’s founding fathers. Unfortunately we must settle for seeing their image through the eyes of artists who painted them, rather than our own.

A few years later Niépce entered into a partnership with Louis Daguerre and began experimenting on a photographic method that required a much shorter exposure time. He abandoned bitumen as his reacting agent and instead began testing a process that involved silver-plated sheets that had been fumed with iodine vapor to form a coating of silver iodide, which reacted to light.

After Niépce’s untimely death in 1833, Daguerre continued experimenting with the process. At first, the exposure time required was still impractically long, but then Daguerre discovered that by fuming latent images created by short exposures with mercury vapors, he could cause a reaction that darkened the faint images, thus “developing” a fully finished photograph.

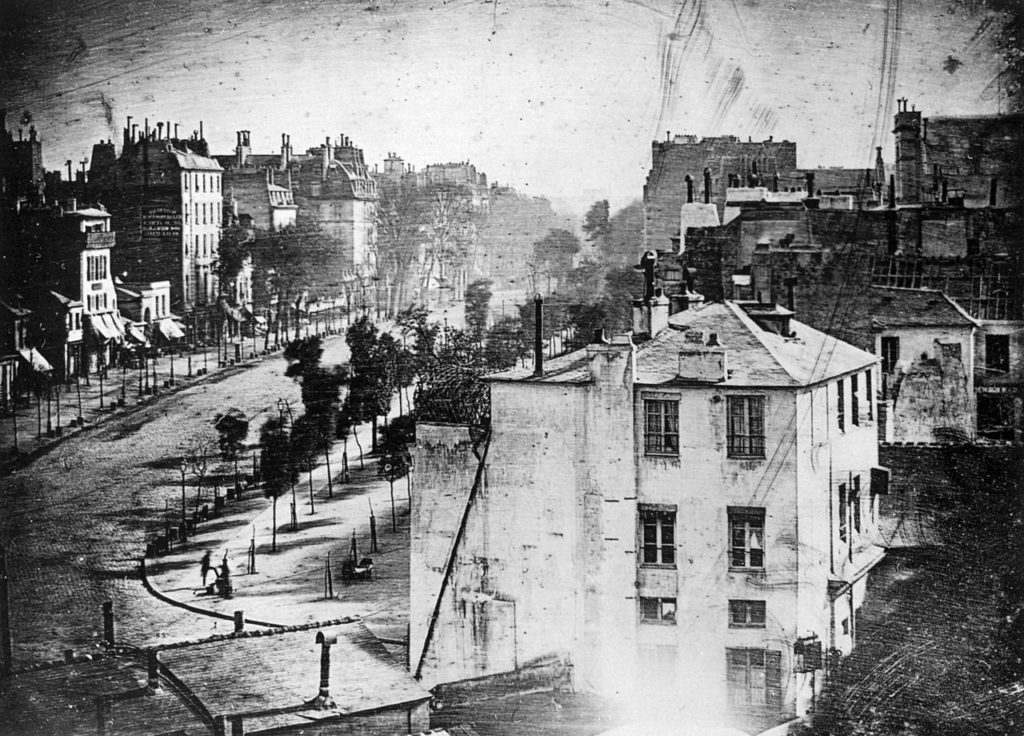

Boulevard du Temple, Paris, 3rd arrondissement, Daguerreotype. Made in 1838 by inventor Louis Daguerre, this is believed to be the earliest photograph showing a living person. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Daguerreotype process was a giant leap forward in the history of photography. Daguerre began successfully producing photos with his new process in 1837 and announced his his invention at a meeting in Paris in 1839. Exposure times were still pretty long. Daguerre’s early photos of city streets in Paris are eerily empty because the crowds of moving people could not be captured by the process. The first photographic image of a human being was of a man who happened to be getting his shoes shined on a street corner while Daguerre was experimenting with his new process in 1838. The hundreds of other pedestrians walking up and down the streets weren’t captured, but while waiting for his shoes to get shined, the man managed to stand still long enough to be captured. You can also sort of make out the man polishing his shoes.

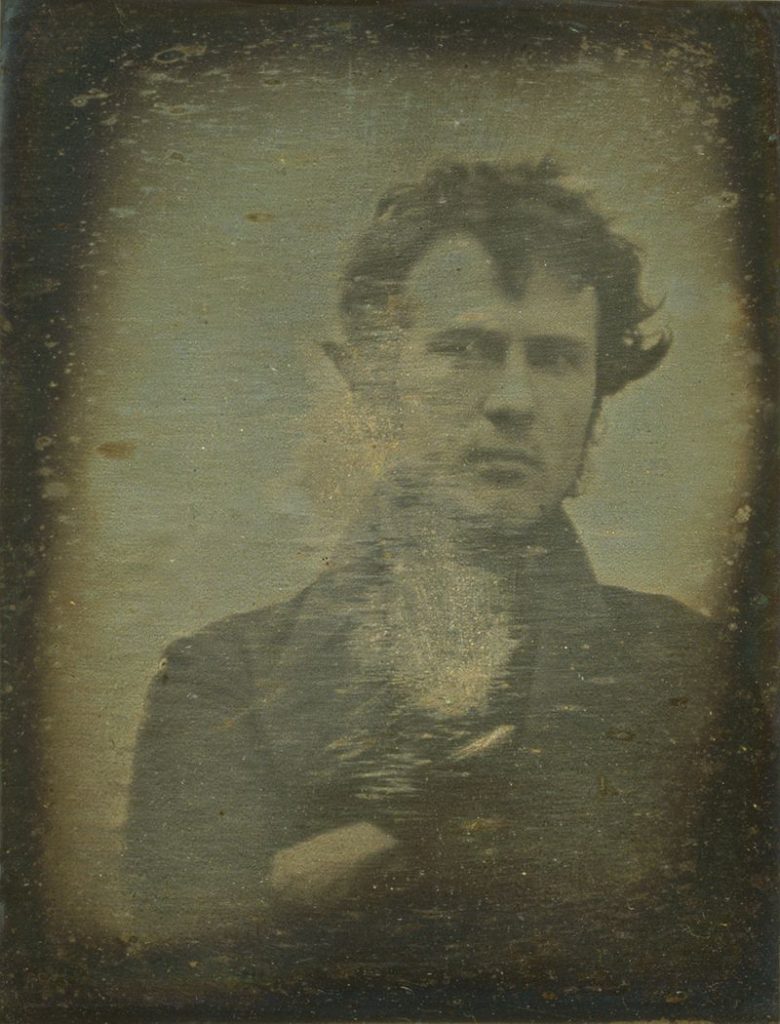

Only a year later the Daguerreotype process gave us the first selfie. In 1839, pioneer American photographer Robert Cornelius turned his lens on himself while experimenting with Daguerre’s process. Check out the result below.

Robert Cornelius, self-portrait, October or November 1839, an approximately quarter plate size daguerreotype. On the back is written, “The first light picture ever taken”. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

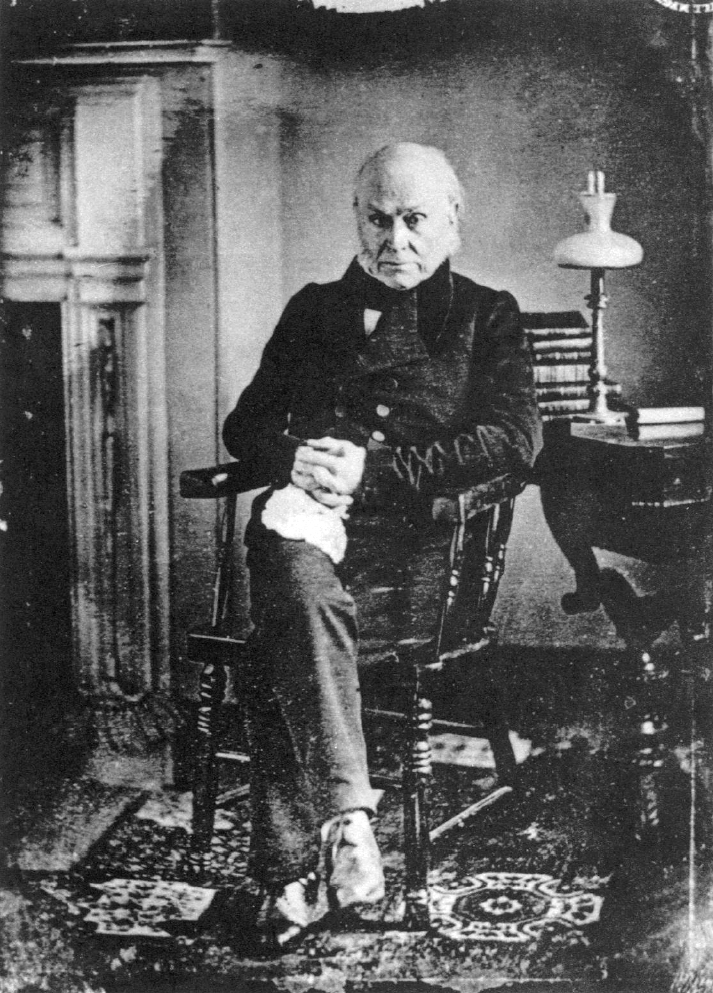

The process also gave us the first photographic image of an American president. John Quincy Adams posed for the photo below in 1843, 14 years after he left office in 1829. We were only one generation away from getting to see what our founding fathers looked like.

John Quincy Adams 1843. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Daguerreotype process was all well and good, but it had one significant disadvantage: it could not be reproduced. The image was a positive image that was permanently affixed to the silver-plated surface of a sheet. Soon, though, other photographic processes were invented that produced photographic negatives of images on translucent glass plates, which could be used to reproduce an unlimited number of prints.

In the 1860’s the Collodion Process, also called “Wet Plate” Collodion, gave us some of the first photographic images of war. The process was extremely difficult, it required the photographer to coat a glass plate in a gelatinous mixture call collodion, then dip the plate in a sensitizing agent that caused the collodion to react to light. Then, he/she had to load the plate into a camera, open the lens to expose the plate to whatever they were taking a picture of and then bring it back to their dark room, all before the mixture dried (hence “wet plate”).

Taking a photograph with the process was a race against time and war photographers were forced to take their darkrooms out into the field with them so that they could rush back and develop their pictures before the colodion dried. That’s why most Civil War photographs record the aftermath of battles rather then the actual events. It wasn’t practical for photographers to be hauling their mobile darkrooms (which were usually wagons or sometimes even specially-constructed tents) through the middle of a raging battle. The process had many shortcomings, but it produced good-quality images that could be reprinted.

During the Civil War photographers took their cumbersome equipment out in the field, sometimes to provide strategic data for the government, other times to record the realities of war for news publications. The pictures they took forever changed the way we viewed warfare. Until the advent of a reliable photographic process, all most people saw of war were the paintings or prints produced by artists who were often attempting to glorify whatever event they were recording. But it’s difficult to glorify reality, and that’s exactly what the cameras were capturing.

Confederate dead overrun at Marye’s Heights, reoccupied next day May 4, 1863. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Besides changing history, photography also changed art. There’s an ongoing debate (which you can read about HERE) about how much influence photography had on the development of impressionist and early modern art styles. It definitely seems like an interesting coincidence that around the time photography was invented there was a huge shift in the art world from Classical and realistic subjects and styles, to more common subjects and abstract styles.

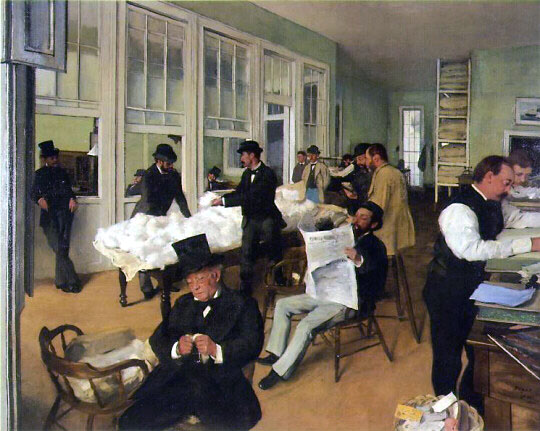

A Cotton Office in New Orleans, 1873 . Artist: Edgar Degas. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Although it probably wasn’t the sole inspiration, photography definitely inspired certain artists to experiment with perspective and subject matter. For example, Degas’ work is known for featuring candid scenes of common people such a laundresses and shopkeepers. His work presents these characters at odd angles, almost like someone is peaking at them from around a corner or peering at them from a chair across the room. Some art historians believe that he was mimicking the products of early photographers who went out into the world with their cameras and captured subjects that had previously been ignored by artists.

The early photographers who may have inspired painters like Degas weren’t trying to start a revolution, they were just goofing around with their cameras. Photographs were novel enough at the time that you didn’t need to produce a highly artistic image to get people’s attention. They would pay to look at any image. But in the process of recording seemingly mundane subjects and exhibiting to a wider public, they accidentally opened a new window into the world of art. People began to see a deeper meaning in mundane actions.

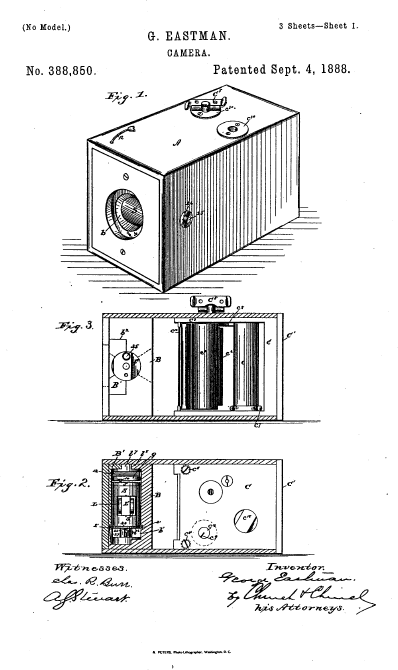

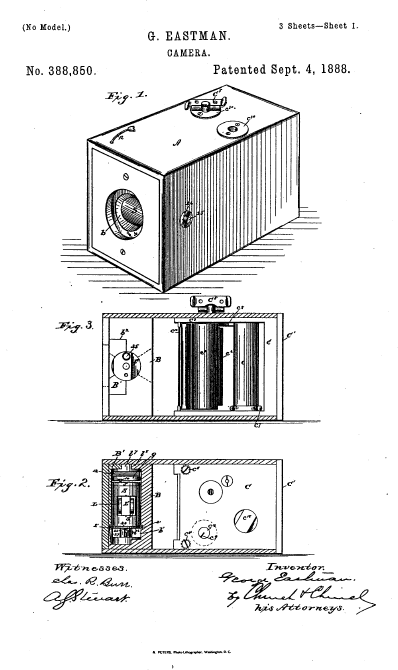

And now we finally arrive at the most important development in the history of photography, if not in history itself: the Kodak camera. Kodak’s first model, the Kodak black, cost just one dollar when it was first released in 1888. Until then, photography had been a complicated process suitable only for professionals and passionate amateurs. But George Eastman’s invention of the dry gelatin process, which did’t require any sort of preparation to sensitize the film, along with his company’s service of developing the film for their customers, meant that anybody could take pictures.

U.S. patent no. 388,850, issued to George Eastman, September 4, 1888. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

This opened up a whole new world of photo-ops for people. Birthdays, weddings, family picnics; they were all photo fodder. Family albums became a thing. Think for a second of all the family photos you’ve seen. You’ll notice that any photos taken before around 1900 are exceptionally creepy; that’s because they are usually stiffly-posed studio photos. After the advent of Kodak’s cameras, people started taking pictures outside, they started capturing moments instead of simply recording their image for posterity.

Silly photos may not seem like a very important thing on the surface, but they preserve the memory of those who came before us so much better than portrait photos. What does a portrait really tell you about someone? Does the slightly scary-looking old photo of your great-grandmother make you feel like you know her? That’s the importance of snapshot photography: the informal sentimentality of it.

Paintings could never capture a snapshot. They are contrived images. No matter how much the artist may try to capture reality, it is still their reality, complete with their own prejudices and preferences. That’s why I wish so much that photography had been invented a little earlier. I want to see Washington and Jefferson and Adams with my own eyes and size them up myself.

So now that we’ve had a fun little discussion about the importance of photography, I want to tell you about our newest exhibit space that has a special focus on the photogenic. Inspired by recently popular pop-up art museum concepts like Museum of Ice Cream, the Flower Vault and Color Factory, InFocus: A Museum Photographic Experience opens up entirely new worlds and provides stunning backdrops for patron’s Instagram. It features four rooms with four different themes that are sure to make great photo fodder.