HMNS’ collections are more than just curiosities, they’re mementos of past lives, each with a story to tell and a lesson to teach. Take, for example, the chunk of pink granite from our Hall of Ancient Egypt pictured below.

This two and a half foot tall rock may look pretty big, but it’s only a (relatively) small fragment of a massive, 80 foot tall obelisk built at the command an 18th dynasty Egyptian pharaoh named Hatshepsut. In fact, you can see an image of her engraved into the fragment’s surface. That’s right, I said her.

Just to put things into perspective: granite is a very hard rock. In fact, it is much harder than the copper and bronze tools that the Egyptians possessed during Hatshepsut’s reign, which spanned 1473-1458 BC. Carving this massive megalith out of pure granite was a monumental process, pun intended. It involved using quartz sand (which has a hardness similar to granite) as basically grit, being ground into the granite’s surface with a copper tool, a bit like sand paper, except without the paper. It was a toilsome and time-consuming process. Hatshepsut had several of them made. She also had temples constructed throughout Egypt, including her own mortuary temple, which is considered one of the most beautiful Egyptian temples still standing.

Djeser-Djeseru is the main building of Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple complex at Deir el-Bahri. Designed by Senemut, her vizier, the building is an example of perfect symmetry that predates the Parthenon, and it was the first complex built on the site she chose, which would become the Valley of the Kings. Author: Steve F-E-Cameron. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Hatshepsut was able to fund these these massive projects partly with riches brought back form a famous expedition she sent to a distant East African trade center called Punt. According to Egyptian records, no pharaoh had been so successful in trade. But it wasn’t only riches from Punt that filled Hatshepsut’s coffers, she ruled over the Egyptian Empire during it’s most prosperous era, riches flowed into Egypt from around the known world.

You would think that an individual like Hatshepsut would be celebrated by Egyptians for generations to come. But that wouldn’t be so, thanks to the efforts of her stepson, Thutmose III.

Thutmose III was the son of Thutmose II and one of his secondary wives, named Isis. Egyptian pharaohs had multiple wives: one queen and many secondary wives of varying statuses. Hatshepsut was his queen, and also his half-sister. Royal relationships are complicated. Unfortunately, Thutmose II was a sickly king and he ended up dying early in his reign, before Hetshepsut could provide him with a son, so Thutmose III ascended to the throne.

When he became king, Thutmose III was only three years old. Not the ideal age for an absolute ruler, but there was no other option. He was the oldest male in line for the throne. There had been female pharaohs in the past, but only 2 or 3 in the 1,500 years of Egyptian history leading up to Thutmose II’s reign. They had been exceptions to the rule. The idea of a woman ruling Egypt as pharaoh was not considered a serious option. Luckily, the Egyptians had a contingency plan. If a pharaoh who was too young to rule effectively ever ascended to the throne, it was traditional for the queen to act on his behalf until he came of age. So Hatshepsut became his regent.

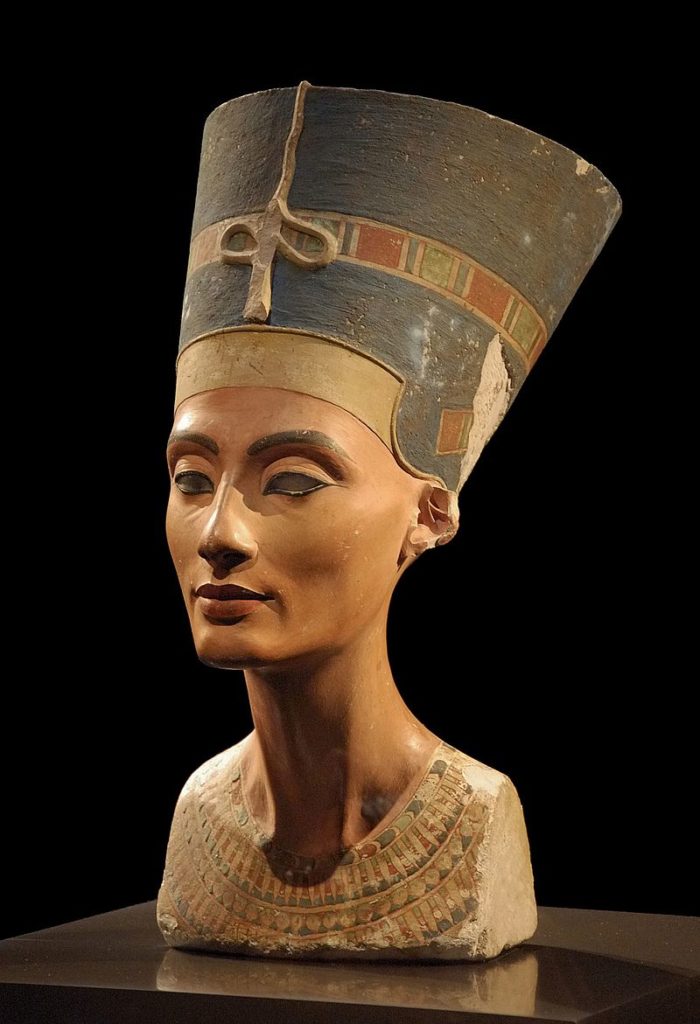

Hatshepsut, Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt, c. 1473-1458 B.C. Indurated limestone sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Author: User:Postdlf . Source: Wikimedia Commons

However, 7 years into her regency, Hatshepsut had herself declared king. She began being depicted in temple inscriptions and statuary as a male wearing the traditional regalia of a pharaoh. She ruled for around 15 year until her death in 1458 BC.

When archaeologists first uncovered statues of Hatshepsut in the 19th century, they noted that any identifying features of the person who the statues were meant to represent were chiseled away. Hundreds of her statues were found, all smashed an mutilated. Some associated inscriptions which managed to survive the devastation named the mysterious pharaoh behind the monuments: Hatshepsut. Although the figures and images definitely depicted male bodies, the inscriptions associated with them were often written in the feminine form.

As more surviving inscriptions were found in temples across Egypt, a story began to form in the imaginations of early egyptologists. It was the story of a power-hungry, mad queen. A cross-dressing despot. It became apparent that at some point after coming to the throne, Thutmose III initiated a massive campaign to erase all evidence of his stepmother’s reign from history. It was interpreted as his revenge against one bad mother. For more than a century, history books miligned Hatshepsut with this rather unflattering description of her reign.

Recently, however that interpretation is being turned upside down. The biggest evidence against the evil stepmother hypothesis is the fact that Thumose III was still alive to claim the throne after Hatshepsut’s death. Any reasonable usurper would have had the true heir murdered. Not only was Thutmose III not murdered, he was given an education and military training. Hatshepsut even put him in charge of her armies shortly before her death. That’s a lot of power to put in the hands of someone who supposedly hates you.

Osirian statues of Hatshepsut at her tomb, one stood at each pillar of the extensive structure, note the mummification shroud enclosing the lower body and legs as well as the crook and flailassociated with Osiris—Deir el-Bahri. Author: Steve F-E-Cameron. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The interpretation supported by most egyptologists today is that Hatshepsut crowned herself king in order to preserve her family’s (including her stepson’s) royal status. Not only was Thutmose very young when he ascended to the throne, he was also the son of a secondary wife. This combination of less than ideal characteristics for a king made him vulnerable to attempts to usurp his power by other Egyptian nobles, who most certainly would have had him murdered in order to secure their rule.

So Hatshepsut did what she thought was best for her stepson, making sure to groom him to become Egypt’s next ruler upon her death. And for all her efforts, she got erased from history. I suppose that’s one thing most mothers can be grateful for this Mother’s Day: not being obliterated from the historical record.

But why did Thutmose III do it? The theory is that he was trying to erase the stain of female kingship from his dynasty’s memory. Scholars say he may have felt that having a female king set a dangerous precedent and that it was best for society to forget. Who know, if Thutmose III hadn’t erased his stepmom from history, maybe we would have had many more female rulers in the ensuing millennia!

As for the cross dressing, the male depticions of Hatshepsut are actually further evidence for how undesireable female kings were in ancient Egypt. For the Egyptians, a pharaoh’s image was more than just art, it was symbolic. You may have noticed that most images of Egyptian pharaohs look almost exactly alike. Most people seem to chock that up to Egyptian art being primitive, but in reality the Egyptians were great artists who were fully capable of creating highly realistic art. They chose to depict pharaoh’s similarly because the image of a pharaoh is loaded with symbolism and meaning. If you change the image, you change the meaning. As far as Hatshepsut and her contemporaries were concerned, if Hatsheput was pharaoh, then that is how she must be depicted. The idea of a male king was so firmly established in Egyptian culture and religion that there was no other option.

Hatshepsut is probably the most underappreciate mother in history, so I thought it would be fitting for her true story to be told on Mother’s Day. For any sons or daughters out there, be sure to treat your mom like an Egyptian pharaoh today, it’s the one day of thanks she gets in return for 365 days of enduring love and affection.

If you’re looking for something to do with mom this weekend, consider visiting the Houston Museum of Natural Science! You can check out our amazing Hall of Ancient Egypt and pay homage to history’s most underappreciated mother while you’re there!