By Jeff Cummins, Horticulturist at the Cockrell Butterfly Center in the Houston Museum of Natural Science

The Cockrell Butterfly Center was graced (?) a couple of weeks ago by a very special event. One of our corpse flowers, Lou, bloomed for the very first time! Lou is an Amorphophallus peaeoniifolius, a smaller species than its famous cousin Lois, our Amorphophallus titanum, and has been in our botanical collection for a few years now growing and storing enough energy to produce a flower.

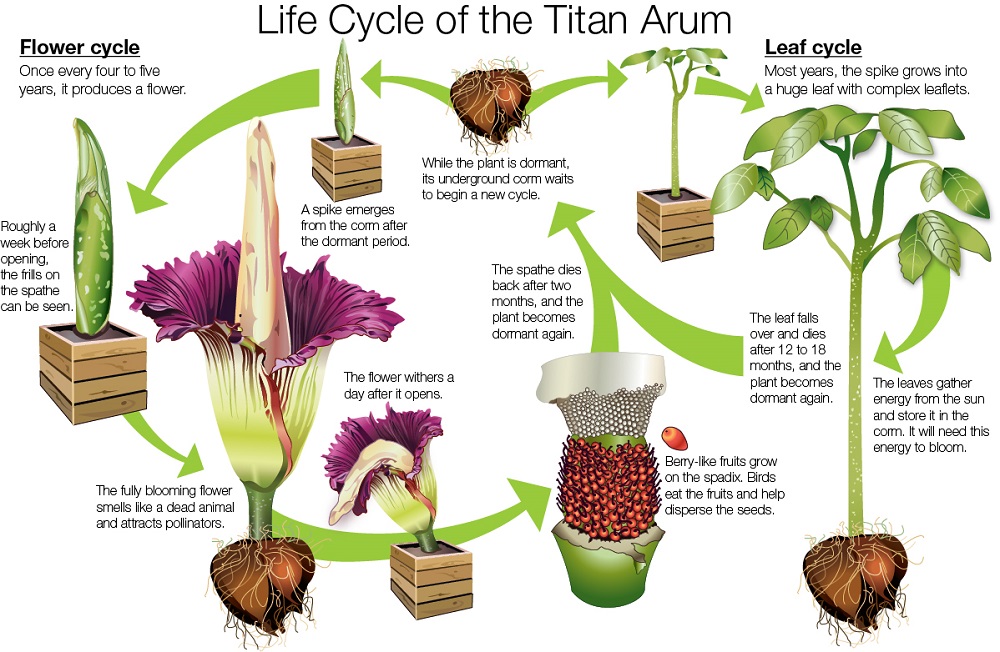

Lou is a member of a large group of plants known as the Arums, or Araceae. This family includes many well-known house plants like Philodendrons and the Spathiphyllum, or Peace Lily, which inhabit nearly every office space in the world. Amorphophallus as a genus is pretty large with about 170 currently accepted species. They vary in shape and size from the tiny A. pusillus to the largest inflorescence in the world of A. titanum. All share a similar life cycle in that they grow from underground organs called corms that produce palm like leaf structures called petioles.

Amorphophallus peaeoniifolius has a fairly wide native distribution. It can be found from the Indian subcontinent, through southern China, Southeast Asia, and northern Australia. It is also grown in tropical regions of Africa as a food crop where it has escaped cultivation and has naturalized. It takes special preparation, however, to make the plant edible because it’s extremely toxic! Many plants in Araceae are loaded with calcium oxalate crystals that induce extreme pain and burning reactions to the skin and mucous membranes if ingested. The corm must be boiled for several hours, dried, boiled again, then dried and ground into a flour before it is safe to consume.

What makes Lou and some of its cousins so appealing (?) are their huge grotesque flowers with their stomach turning smell. The odor is a concoction of volatile chemicals produced by the plant that can only be described as horrible… think elephant carcass that’s been sitting in the sun putrefying for a good week or so. As with all flowers, the goal is pollination and reproduction. The odor is produced to attract species of carrion flies and beetles. While Lou’s flower lasted for about 5 days, the smell was only produced once it was fully open and only for the first two days. This has everything to do with its pollination strategy. During the first two days Lou was in its “female phase,” at which time the pistillate (female) flowers were open and receptive. In the wild, flies and beetles would be attracted by the smell from miles around thinking there is a dead animal for them to eat and lay their eggs on, but instead find only a flower. Some of these insects would hopefully have been fooled by another corpse flower the day before and be covered in pollen which then can be delivered to the receptive pistillate flowers. That evening the spathe, the large sheath that surrounds the spadix, closes slightly to trap the insects inside for the night. The next morning, with the pistillate flowers successfully pollinated, the plant converts to its “male phase.” Pollen bearing staminate (male) flowers open covering the insects in pollen granules. The insects are then released to hopefully find another smelly flower elsewhere in the forest.

In fairness, it should be noted that not all Amorphophallus smell awful. Some species have adopted more pleasing (to us) scents to attract their pollinators. Amorphophallus albispathus has sweet licorice scent; A. odoratus smells like freshly peeled carrots; A. manta smells like cocoa powder!

There’s more to the story, however! Plants in Araceae are special in that they can generate their own heat! There are only a few other families of plants that can do this. They have metabolic processes where they burn sugars to increase their internal temperature. Now, the exact reasons for this are still being debated, but heat is produced only while the female parts of the plant are active. This is also the smelliest time of the plant. Increased temperatures help to volatize the odor, sending it high into the air to attract more pollinators. It’s also thought that this heat protects the insects while they’re inside the bloom. Even in the tropics it can get pretty cool at night, and since insects are exothermic they are only active when they’re warm. Keeping them nice and toasty through the night and into the next morning means that they will be charged and ready to fly off the next morning to hopefully find another Amorphophallus bloom.

Finished blooming, Lou has been moved back to our greenhouses to recover alongside his cousin, Lois. Amorphophallus peaeoniifolius bloom on average once every five years. It takes that much time for the plant to store up enough energy to produce its large and complex flowers!