How many of you readers collect something, whether coins, stamps, statues of elephants, vintage firearms, beanie babies (we’re dating ourselves!), shot glasses from places you’ve visited, etc.? Humans seem to have a predilection for collecting things. Some of these collections seem random, or nostalgic, or even silly – but in the case of museums, a collection can have an important function. Being able to compare different fossils, plants, insects, shells, animals, etc., collected from many different times and places gave rise to the discipline of taxonomy, or classification – which in turn is the cornerstone of our understanding of evolution. Collections also give us valuable information on species’ ranges/distributions and changes in animal and plant populations due to human and other factors.

The Europeans, especially the British, were perhaps the most avid collectors of natural history and anthropological objects in history. The discovery of the New World ushered in a prolonged era of ocean voyages to explore the unknown parts of the globe. Many “Voyages of Discovery” were sent out with the precise goal of collecting unfamiliar plants and animals from newly encountered lands. Most of these long exploratory trips had biologists and artists along, to collect, sort, and document the findings. Collecting various artifacts also became popular among the wealthy class. The Victorians were particularly fascinated with collecting: our exhibit “Cabinets of Curiosity” replicates some of the collections of this age. Furthermore, some of the collections made on these exploratory trips became the raisons d’être for the first natural history museums, such as the Natural History Museum of London.

Because insects are small and incredibly diverse (some estimate the world may hold up to 30 million different species), making collections of them came naturally to people interested in the natural world. Did you know that Charles Darwin was an enthusiastic beetle collector even before he earned fame as the naturalist aboard the Beagle?

What does an insect collection look like?

Since the 1600s, insect collectors have mounted their dead specimens on long, non-corrosive pins after killing them, usually with some sort of toxic gas (ether, carbon tetrachloride, cyanide, or ethyl acetate are just some that have been used). Most adult insects don’t have much in the way of fleshy body parts, so they look much the same when they are dead and dried; i.e., unlike vertebrates, they don’t need any special preservation techniques. If they are kept out of direct light, away from moisture, and protected from the ravages of pests (especially certain other insects that like to eat dead ones), these dried collections can last intact for a very long time. Case in point: in 1999, HMNS hosted a wonderful exhibit documenting some of Britain’s early exploratory voyages. The section on Sir Hans Sloane, a British medical doctor who collected in Jamaica from 1687-1689, included a couple of gulf fritillary butterfly specimens (also found in Texas). Despite being over 300 years old, the butterflies were only slightly faded, not much different from some of the specimens in our own collection.

How are Insects Mounted?

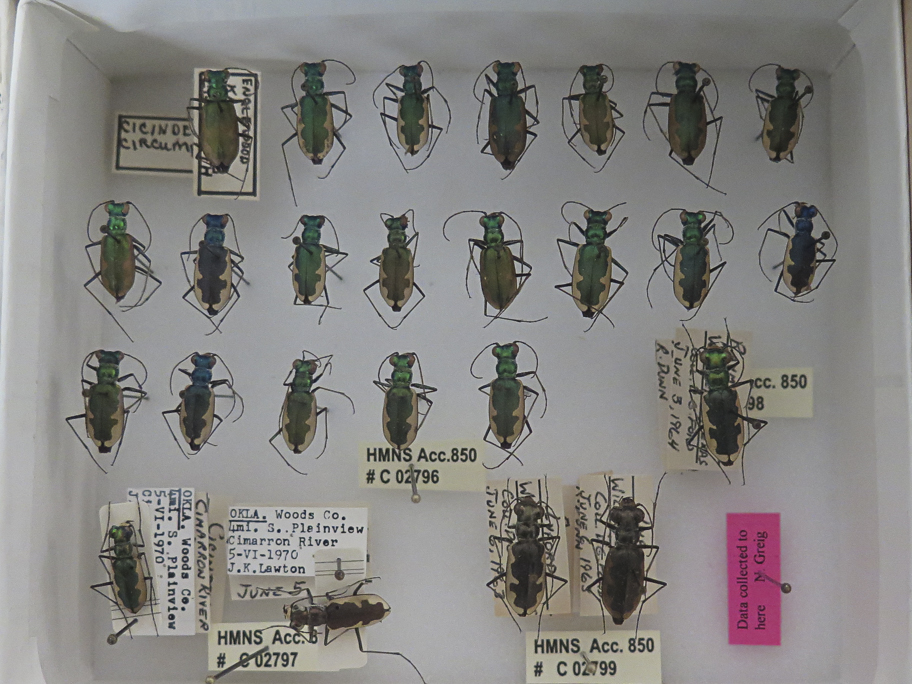

Insects with large, non-folding wings such as butterflies and moths, and dragonflies, are pinned through the center of the thorax, with their wings spread open so that both wing surfaces can be observed. Most other insects traditionally are pinned through the thorax just to the right of the midline, often with their wings closed (sometimes bees and wasps have their wings spread open). Of course, the most important part of a specimen is the label, which lists when and where (and ideally by whom) the specimen was collected. Without this information, a specimen, no matter how perfect, has no scientific value.

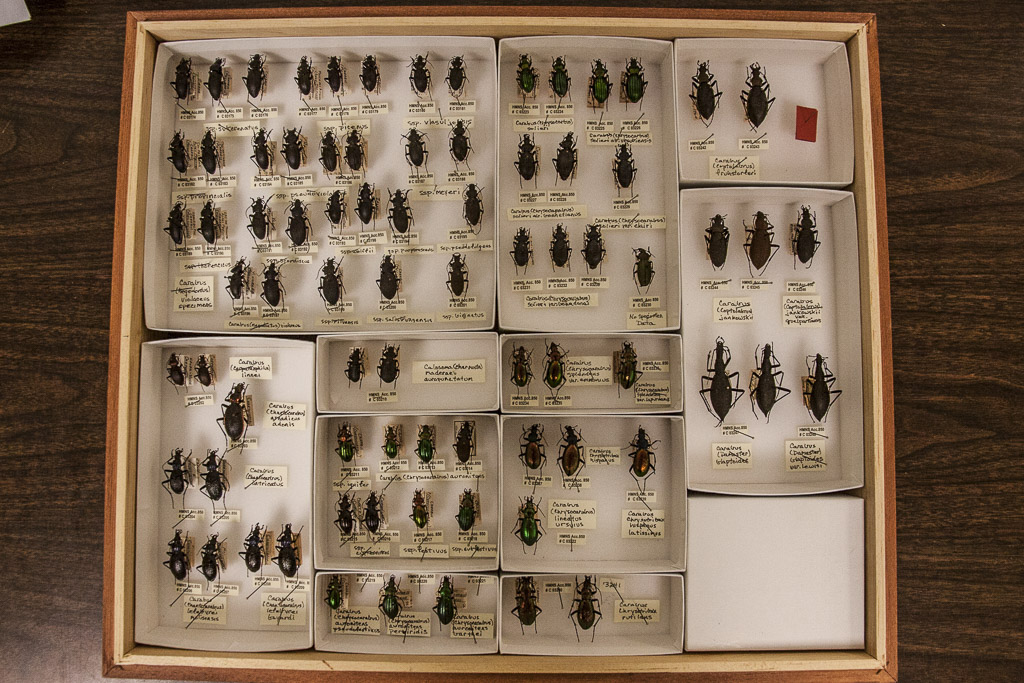

The tradition of mounting insects on pins has a number of advantages. It is easy to handle the dead insect without damaging it by holding onto the head of the pin. The insect can be held up and examined from all sides. This is important in identification, as for some insects (beetles for example), several diagnostic features can be found on the underside. The all-important label can be stuck onto the same pin underneath the insect. Pinned insects are easy to store, as well: a large number of specimens can be kept in shallow boxes with soft bottoms (balsa wood, cork, or today, plastic foam) for storage and/or safe transport.

How Insects Are Stored

The most commonly used insect storage box today is called a Cornell drawer, after Cornell University. Cornell drawers are 19 x 16-1/2 x 3″ (outer dimensions) with glass tops. Sometimes, for organizational purposes, insects are placed into smaller “unit trays” – foam-bottomed cardboard boxes that come in a range of sizes designed to fit snugly into the larger Cornell drawers. Individual Cornell drawers are traditionally stored in an upright metal cabinet called a Lane cabinet, each of which holds up to 25 drawers. A large collection will have dozens or hundreds of Lane cabinets (see photo).

The HMNS Entomology Collection

The Houston Museum of Natural Science’s insect collection is fairly typical in this regard. We have over 50 Lane cabinets, most of which are close to full of Cornell drawers. We also have several containers of as yet unmounted, unsorted specimens (mostly butterflies). However, our collection is quite small as compared to other places with major insect holdings. HMNS does not even appear on the list of the top 30 insect collections in the world (only collections with 5 million or more specimens are included). Natural history museums in Paris, London, DC, NYC and Munich all have insect collections numbering over 30 million specimens. In Texas, the insect collection at A & M University in College Station, which offers one of the best entomology programs in the country, is the state’s largest, with some 2.8 million specimens.

Prior to 1987, HMNS had only a few hundred insects in the collection, mostly amateur collections donated to the museum over the years. But in 1987 the museum board decided to purchase the so-called “Whitley Collection,” which included over 100,000 specimens. This collection makes up over 90% of the collection today.

The name comes from Mike Whitley, a taxidermist by avocation, who lives west of New Waverly. Whitley had a passion for collecting and mounting butterflies and moths, and personally collected hundreds of showy local species. He also bought “papered” specimens (so called because they are stored in glassine envelopes, i.e., the waxy envelopes used by stamp collectors) from dealers around the world. Whitley’s taxidermy skills came in handy as he mounted the insects he acquired – he was exceptionally meticulous in choosing perfect specimens and in positioning their wings and antennae symmetrically. He favored large and spectacular species, including the rare birdwing swallowtails, peacock swallowtails, the coveted Agrias butterflies from South America, and giant silk moths from around the world, among others. Many of the species Whitley acquired from abroad are now impossible to obtain. Some, such as the birdwings, are today so highly endangered that they are on the CITES lists (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species – such animals or plants cannot be exported from their country of origin). Others originate in places that no longer allow collecting of their natural fauna without governmental permits (e.g., India, Mexico, Brazil).

Mr. Whitley had also purchased a large beetle collection, apparently acquired from another individual who had had to sell the collection to make ends meet. This collection includes many beetles collected in the American southwest and central/South America in the early 1900s, mostly by two collectors named Smythe and Willis. Whitley also bought (again through the “paper trade”) some of the world’s largest and showiest beetles to enhance the collection.

Whitley put many of the showy specimens, arranged into fanciful or educational displays, in glass-fronted drawers and displayed them in a series of trailers near his home. This had some local fame as the “New Waverly butterfly museum.” But falling on hard times, Whitley was forced to put his collection up for sale. The collection’s availability came to the attention of one of the members of the museum’s supervising board. Long story short, the museum decided to buy the collection in 1987.

Acquiring the Whitley Collection was in fact the impetus for constructing the Cockrell Butterfly Center. As the museum board and staff pondered what to do with this showy collection, they investigated other insect-oriented displays around the country – and discovered the newly popular live butterfly exhibits at Callaway Gardens in Georgia and Butterfly World in Florida, as well as some of the “immersive” rainforest exhibits at the Bronx Zoo and Baltimore Aquarium. Ernie Cockrell, former board president and long time board member, became particularly enthusiastic (his wife Janet loves butterflies) and came up with major financial support for the construction of a large and unusual greenhouse-like structure designed to house living plants and butterflies. Indeed, exhibiting the Whitley Collection became more of an afterthought to the proposed Cockrell Butterfly Center. The first permutation of the Brown Hall of Entomology hall attached to the Butterfly Center did display hundreds of insect specimens. But when we reworked the hall in 2007, we retired many of the specimens (some of which had become very faded due to 13 years of exposure to light) in favor of the more varied and interactive exhibit that visitors experience today. However, you can still see plenty of real specimens illustrating some of the exhibits in the upper level, or in the glass-topped display drawers in the “Entomologist’s Lab” section in the lower level.

Insect collections in most natural history museums and universities are primarily used behind the scenes by curators, professors and students conducting research on a variety of topics in insect biology (taxonomy/systematics, species distributions, population changes, etc.). Our rather unusual collection, with its emphasis on a limited subset of butterflies, moths, and beetles, many of which were purchased and not collected in the wild, is (with some exceptions) not really suited for research. However, the preponderance of large, showy specimens makes our collection excellent for impressing visitors and opening their eyes to the beauty and diversity of insects. In addition to providing specimens to illustrate and enhance the exhibits of the Entomology Hall, we use specimens from the collection for “show and tell” in outreach presentations, and have donated (or loaned) displays of local butterflies and moths to a few local natural history venues (the Houston Arboretum, for example).

When we acquired the Whitley collection, it was not in perfect condition. The beetle collection in particular was disorganized and many drawers had pest damage or overcrowded specimens. In a number of drawers the foam bottoms had shrunk (the old fashioned method of fumigation using moth crystals causes Styrofoam to shrivel and contract. Today we use a new kind of foam, and avoid using moth crystals as a fumigant). Over the years since the opening of the Butterfly Center in 1994, several summer interns and interested entomologists have helped us to organize the collection and transfer it to new drawers. Farrar Stockton, a part-time employee since 2004, has been especially involved in curating the butterflies and moths (those being a personal passion of his).

In 2014, the museum began using a collections database called KE-Emu, and since then a major task has been to enter all the specimens (insects, shells, fossils, etc.) into that database. Farrar spends most of his time these days, now that the insect collection is stable in terms of its condition, entering the information on the labels attached to each specimen: slow, painstaking work, but very important. The database will allow us to know easily how many specimens of each species we have in the collection, plus where exactly to find them (both in the collection or on display or on loan somewhere). It will also allow the public to learn more about our collection and about the specimens it holds. The sophisticated KE-Emu system also allows for photos and links to be attached, so eventually, typing in a specimen entered into the database will bring up a whole slew of information.

We are not yet doing this at HMNS, but today many collections actually use bar codes on each specimen, which can be scanned to bring up all the relevant information on that item.

Although our collection is not a traditional one, it is a tremendous resource for the museum. What the public sees in our public displays, of the entomology collection and indeed of all the museum’s collections, is just the tip of the iceberg. On special occasions, such as for adult behind-the-scenes tours or for summer camps, participating individuals are shown a glimpse of the treasures we keep protected in our offsite storage facility (a specially constructed building with climatic and security features designed to best protect the collections). For these events, staff open the Lane cabinets so people can marvel at well-organized Cornell drawers filled with multiple specimens of, for example, close to 100 different subspecies of iridescent Morpho butterflies, gasp at the brilliantly colored but incredibly fragile tropical hairstreaks, peruse the unusual and rare high-elevation swallowtails called Parnassians, or see dozens of the uncommon black female form of the local tiger swallowtail, in addition to ogling specimens of the largest moths and largest beetles in the world. For most, seeing even our relatively modest collection is an awe-inspiring experience and gives a deeper understanding of the importance of collections to museums and to our understanding of the world.

We have visited other live butterfly exhibits (busman’s holiday) at numerous other institutions. Some of these have fantastic living displays (Butterfly World, Key West, Fairchild Tropical Gardens, Niagara Falls, etc.). However, having the collection of mounted specimens allows HMNS to have – in our humble opinion – the best accompanying entomology hall, which enhances and enlarges the public’s experience of the truly wide and wonderful world of insects.

About Farrar Stockton, Assistant Curator, Entomology Collection

Farrar Stockton has a passion for nature, especially butterflies and moths. After retiring from a career in banking, he started helping out with the Entomology Collection at HMNS. His duties include maintaining the collection, in addition to numbering, cataloguing, and entering specimens on the database. Farrar also help to choose specimens for the permanent displays now used in the CBC and at the Houston Arboretum. His volunteer work includes being the President of the North American Butterfly Association (NABA) – Houston Chapter, and a Board Member of the Piney Woods Wildlife Society. He also loves travel and photography.