By Mylynka Kilgore-Cardona, PhD, Map Curator, Archives and Records, Texas General Land Office

In the nearly four hundred years that it took for Texas to take its current shape, the space changed from an extensive, unexplored and sparsely settled frontier under the Spanish Crown to its iconic and easily recognizable outline. Mapping Texas: From Frontier to the Lone Star State traces the cartographic history of Texas from the sixteenth to the twentieth century, from contested imperial claims that spanned the continent to individual rights of ownership all with the understanding that in order for a place to be claimed, it needed to be mapped. Over fifty rare maps from the collections of the Texas General Land Office and the personal collection of Frank and Carol Holcomb, of Houston, are on display. Additional maps are on loan from The Bryan Museum in Galveston and the Witte Museum in San Antonio. This exhibit runs at the Houston Museum of Natural Science through October 8, 2017

Frontiers of Discovery: “The Great Space of Land Unknown”

European cartographers imagined the territory that became Texas as a vast region eager to be claimed and colonized despite the existence of indigenous communities. Mapmakers borrowed from native informants, European explorers’ writings and other printed sources to chart coastal areas and waterways and ease the navigation and exploration of the territory. Their vague, and often contradictory, information led to contested claims that fueled further exploration. These campaigns spurred the eventual establishment of fortifications and cities from which to govern the territory. While Spain and France made inroads into territorial claims in Texas, England concerned itself with charting the waters of the Gulf.

Nveva Hispania Tabvla Nova

Currently the oldest map in the holdings of the Texas General Land office is Girolamo Ruscelli’s (1504-1566) map of New Spain. Ruscelli was a Venetian publisher and scientist, and his map is an excellent example of how mapmakers borrowed from each other. This work is an updated version of Giacomo Gastaldi’s Map of New Spain (1548). Like Gastaldi before him, Ruscelli produced it for an Italian version of Ptolemy’s Geographia.

Girolamo Ruscelli, Nveva Hispania Tabvla Nova, Venice, 1561, GLO Map #93796, General Map Collection, Texas General Land Office, Archives and Records Division, Austin, TX.

The Geographia, originally published in 150 CE, was Claudius Ptolemy’s (100-168CE) terrestrial atlas. Ptolemy, a second-century CE Egyptian mathematician, geographer, and astronomer, used a system of longitude and latitude on his maps to locate places.[1] Though not a new concept, Ptolemy’s mathematical refinement of the projections of Earth’s land masses by the use of latitude and longitude are his lasting contributions to cartography – stimulating the quest for a more precise way to measure the Earth.[2] Though no copies of the original maps in Geographia remain, Ptolemy left behind copious notes allowing for the reproduction of the atlas for centuries.[3]

Because of its three-pronged nature – as geographical dictionary, treatise on the cartographical knowledge of the Roman Empire in the second century CE, and known-world atlas – the Geographia was one of the ancient texts revived during the European Renaissance, translated into Latin, and printed. Some editions remained faithful to Ptolemy’s original notes and others, like those by Gastaldi and Ruscelli, updated the maps and information to what was known in the fifteenth century CE.[4]

Portrait of Girolamo Ruscelli with figures holding his “Book of Secrets” on their laps as angels herald overhead.[10]

Reportedly the founder of the Accademia Segreta, one of the first scientific (and secret) societies in Renaissance Italy, Girolamo Ruscelli was a humanist known for his vast intelligence and his writings on subjects as varied as the rules of Italian poetry and the design of armor. In addition to his editorial skills, he also studied geography, philosophy, geology, and alchemy. Under his pen-name Alexius Pedemontanus, Ruscelli published a famous “Book of Secrets” about the goings-on of the Accademia Segreta – which was published continually, and in several languages, well into the eighteenth century.[5]

In his 1561 edition of the Geographia, Ruscelli updates it to include a new map of New Spain. He shows Mexico City very near the Gulf of Mexico. The capitol city is also depicted as an island in the middle of a large lake. First rendered in 1524 in the publication of Hernán Cortés’s letters about his explorations in the New World, Tenochtitlan (Mexico City) is an “impressive metropolis set like a jewel in the centre of an azure lake.” Cortés’s Tenochtitlan set the standard for the cartographic look of Mexico City through the seventeenth century. His map also provided a standard look at the Gulf of Mexico as well.[6]

A vast mountain range from Texas to Central Mexico divides the known world from the mythical seven cities of gold in the west (indicated by red castles). The so-called Seven Cities of Cibola were a lure to the Spanish Conquistadors and spurred many expeditions to the interior of New Spain in search for great wealth.[7]

Detail of map showing Baja California and the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola, which were rumored to be made of gold and contain immense wealth.

Just like Gastaldi before him, Ruscelli places mountains across much of the area that would become Texas, a cartographical error that would be repeated on maps for the following two centuries – as evidenced by Italian engraver Paolo Forlani’s Il Designo del discoperto della noua Franza… (1565), Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius’s landmark world map America Sive Novi Orbis Nova Descriptio (1570 and later editions), Dutchman Jodocus Hondius’s America (1606), French Geographer to the King, Nicolas Sanson’s Amerique Septentrionale (1650), and the Philadelphia engravers Lotter & Lotter’s A New Correct Map of North America… (1784), along with many others.

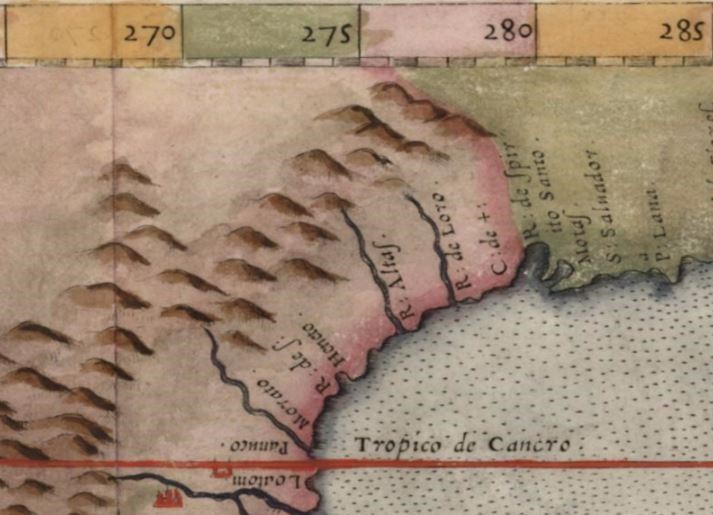

Although the details of the interior of Texas were erroneous, Ruscelli’s Gulf Coast, even as compressed as it is, is recognizable. The no-longer-existing cities of Panuco, Morato, and Cape of the Cross (C: de +: ), as well as the city of Mota, at the mouth of the Mississippi (R: de Spirito Santo) are all indicated. The rivers Atlas, de Loro, and San Heneto are also represented. Though not recognized today, the details Ruscelli added to the map were based on the reports Spanish explorers sent back to Europe.[8]

Detail of the Texas Gulf Coast showing the known rivers and the mouth of the Mississippi (Rio de Spirito Santo).

Ruscelli’s map of New Spain expanded and updated Ptolemy’s Geographia. He corrected a major error on Gastaldi’s map, that the Yucatan peninsula was not an island, and furthered the knowledge of the sixteenth-century American holdings of Spain. These achievements were important contributions to sixteenth-century cartography, and as the oldest map in the GLO Archives, Ruscelli’s map today remains an excellent contribution to the long history of mapping Texas.

Latin text on the reverse of the map relates experiences and observations of explorer and first Spanish Governor of New Spain, Hernán Cortés.

Can’t make it to Houston? You can view the majority of the maps in this exhibit in high definition on the GLO’s website where you can also purchase reproductions of the maps and support the Save Texas History program.

[1] The use of longitude and latitude is the best way to locate points on a round surface.

[2] http://www.uh.edu/engines/epi2594.htm; Also see Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration, (New York: W.W. Norton, 2006), 32; For more on the Ptolemaic model and his methods, see Christian Jacob, “Mapping in the Mind: The Earth from Ancient Alexandria,” in Mappings, Denis Cosgrove, ed., (London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 1999), pp. 24-49.

[3] For more on Ptolemy’s Geographia see https://www.geolounge.com/ptolemys-geographia/

[4] For more on the map making taking place in Venice in the 1500s see Daniel Brownstein, “Mapping Land and Sea in Venice (and Elsewhere), ca. 1500,” Musings on Maps, July 18, 2013, accessed November 22, 2015, https://dabrownstein.com/2013/07/18/mapping-land-and-sea-in-venice-circa-1500/

[5] It is assumed that Ruscelli was Alexius Pedemontanus, though he never confirmed it. For more see, Girolamo Ruscelli, William Eamon, and Francoise Paheau, “The Accademia Segreta of Girolamo Ruscelli: A Sixteenth-Century Scientific Society,” Isis, Vol. 75, No. 2 (June., 1984), pp. 327-372, http://www.jstor.org/stable/231830, accessed 9 December 2016; For more on the Italian secret societies of the sixteenth century see William Eamon, “Science and Popular Culture in Sixteenth Century Italy: The “Professors of Secrets” and Their Books,” The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 16, No. 4 (Winter, 1985), pp. 471-485.

[6] Barbra E. Mundy, “Mapping the Aztec Capital: The 1524 Nuremberg Map of Tenochtitlan, Its Sources and Meanings,” Imago Mundi, Vol. 50 (1998), p. 11. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1151388 Accessed: 9 December 2016.

[7] For more on the fabled cities of Cibola see http://science.nationalgeographic.com/science/archaeology/seven-cities-of-cibola/ and http://www.pbs.org/weta/thewest/program/episodes/one/cities_ofgold.htm

[8] Vittore S. Grandi, Sistema Del Mondo Terraqueo Geograficamemta Descritto…., (Venice: Bragandina Press, 1716), pp 167-168. Giacomo Gastaldi and Carlo Claussen, La carte d’America di Giacomo Gastaldi: contributo alla storia della cartografic del secolo XVI, (Turin: Hans Hans Rinck Succ., 1905), pp 48-49.

[9] A Byzantine Greek world map according to Ptolemy’s first (conic) projection. From Codex Vaticanus Urbinas Graecus 82, Constantinople c. 1300. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User%3APortolanero / Wikimedia Commons, via Wikimedia Commons Accessed December 12, 2016.

[10] Niccolò Nelli, 1566, Portrait of Girolamo Ruscelli, 1566, Engraving in black on cream laid paper, Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/188302?search_id=1 Accessed December 12, 2016.