Over the last couple of weeks, eagle-eyed visitors to the Hall of Ancient Egypt may have noticed that things look somehow different. If it’s not any bigger than before, the Hall is certainly better stocked than before – we have added something in the region of sixty new objects to the displays. Most of these come from the Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, and join a number of pieces they have already loaned us.

Over the next few weeks, we’ll be highlighting some of these new objects, and talking about why they’re special and what getting them on display involved – some of them have been specially conserved for display.

The first piece, which you can see in our case on war and weaponry

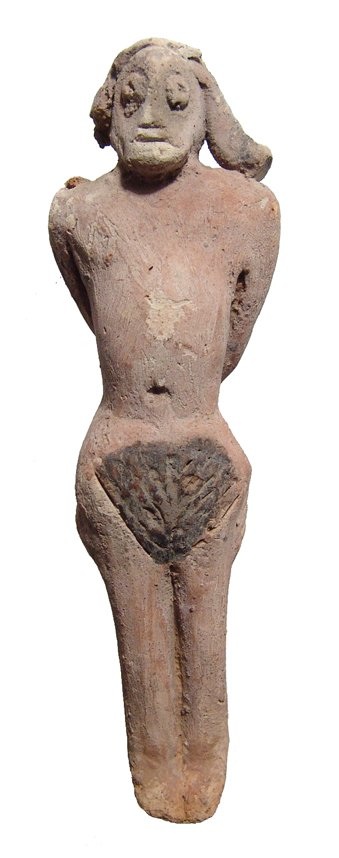

does not look typically Egyptian at first glance. A hand-modelled clay figure shows what looks to be a naked woman. Her head is shaved except for four plaits. Her long legs taper away into an abstracted point, rather than feet, but otherwise she looks cheerful enough. Turn her round, though, and it’s a different story.

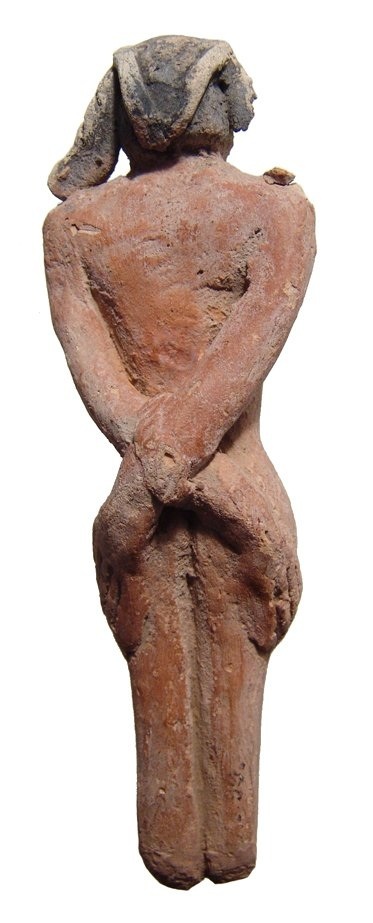

Her hands are tied behind her back, making her a helpless prisoner.

Figures of naked women, made of fired, red-slipped clay (like ours),

‘Courtesy The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology UCL, UC59288 (http://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums/petrie)

stone,

Courtesy The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology UCL, UC59284, rear view (http://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums/petrie)

wood,

Courtesy The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology UCL, UC16148 (http://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums/petrie)

or glazed faience,

Courtesy The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology UCL, UC16725 (http://www.ucl.ac.uk/museums/petrie)

were made in large numbers in the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period of Egyptian history (about 2040 – 1570 BC). Like our piece, they often have shaven heads with plaits, schematic faces, and stumpy or missing feet. Earlier scholars had fun calling them ‘concubines of the dead’, assuming that they were provided to keep the male tomb owner company in the afterlife.

Present interpretations are less single minded. We now call them ‘fertility figures’, and identify them as generic images of women used (by men, women, and children) in rituals and as conduits of prayers associated with birth and re-birth. Magic and medicine were linked together in Egypt, and figurines like these could have been used in healing rites, magically becoming the goddesses needed to fight illnesses. Our figure could be one of these ‘fertility figures’, but what about her bound hands? Is this a case of Fifty Shades of Terracotta?

It’s more likely that our figure is not connected with fertility but hostility. She is a captive, and as such joins a rarer group of objects. Almost all of these are made of fired clay, and depict figures with hands pinioned like our figure. One figure is in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge UK, but the largest group is in the Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Like the fertility figures, these images also had magical associations, although presumably of a rather different sort. They could represent or stand in for people that the owner of the figure wished to harm, or had succeeded in harming. A slightly different type of these ‘execration figures’ is inscribed with a lengthy text naming the chiefs of neighboring countries “who may rebel, who may plot, who may fight, who may think of fighting, or who may think of rebelling in this entire earth” – a fine early example of legal boilerplate. Many of these figures are broken, and it seems likely that breaking them was the climax of one type of ritual. Attacking the stand-in figures also attacked the persons they represented.

Egyptologists tend to steer away from the question of whether the Egyptians really practiced ritual executions, or just vented their anger on these execration figures. A spectacular recent discovery has forced us to come back to the issue. A team from Johns Hopkins University discovered the trussed and pinioned remains of a man buried inside the temple complex of the goddess Mut at Luxor. Dating around the Second Intermediate Period, like our figure, he had probably been killed by having his neck twisted from behind – almost like wringing a bird’s neck.

I’ve called our figure a woman, but is this correct? A colleague pointed out the difficulty of assigning gender to figures like this, and that clay execration figures are all male – or, at any rate, none are definitely female. What I saw as a naked woman with a big chin and rather small bosom could be a bearded man wearing a triangular loincloth made of slashed leather, typical for foreign soldiers, and probably also worn by the figures in the photograph above.

What I think makes our figure different, though, is its hairstyle. Only women are shown with a shaven skull and plaits; for me this makes the identification as female almost certain. Women were named alongside men in execration texts, so why, sometimes, couldn’t they be given personalised figures? Come and have a look and decide for yourself.

Finally, if you are interested in finding out more about Egyptian magic and execration figures, the standard text on the subject, Robert Ritner’s The Mechanics of Ancient Egyptian Magical Practice can be downloaded free from the University of Chicago.