During the next few weeks, Comet Pan-STARRS will grace our skies as a naked-eye comet. As its name indicates, astronomers discovered this comet on June 6, 2011, using the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System, a planned array of telescopes in Hawaii. This array’s primary mission is to detect near-Earth objects (comets and asteroids with orbits near Earth’s) that pose a risk of impact. Of the four telescopes planned for the array, only the first, PS1, is yet operational. This is the telescope used to discover the comet.

Viewers south of the equator have been observing Pan-STARRS since February, as the geometry of its orbit has favored southern observers until now. However, as Pan-STARRS approached perihelion late on March 9, it also comes up through the plane of Earth’s orbit, making it visible from right here in Houston during mid-March 2013.

Image via Discover Magazine

What are comets?

Comets are made of ice and dust and are often called ‘dirty snowballs.’ They are believed to be left over from the formation of the solar system. Long-period comets such as this one originate in the Oort Cloud, located about 50,000 times as far from the Sun as the Earth. As comets approach the sun, ice changes into gas and the dust embedded within the ice is released. A cloud of particles expands out to form a coma around the comet’s solid nucleus. This coma may be 100,000 miles across. Radiation pressure of sunlight and the powerful solar wind sweep gases and dust away from the comet’s head into a tail spreading millions of miles behind the comet and pointed away from the Sun. Comets have bluish gas tails and yellowish dust tails.

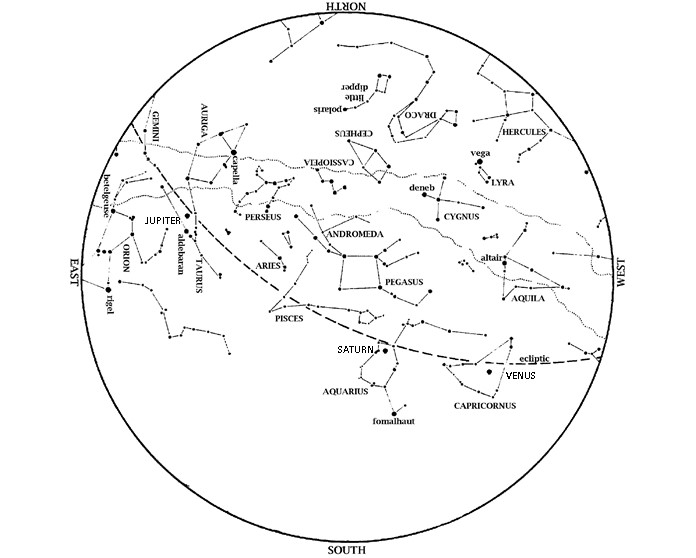

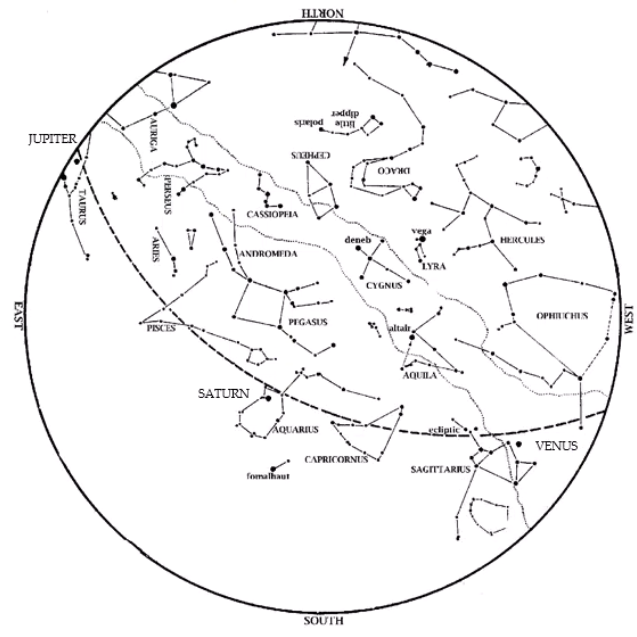

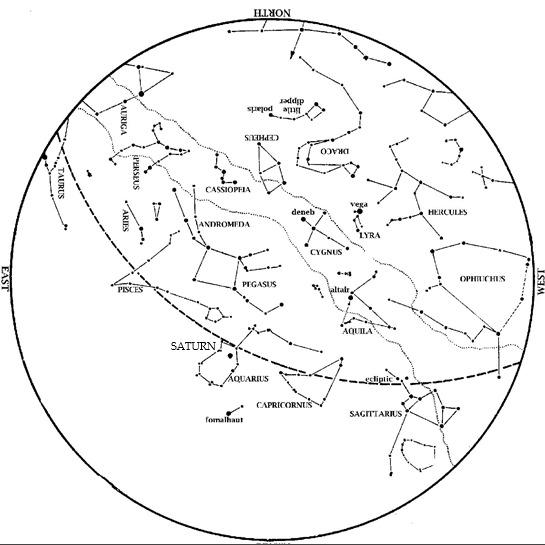

Where should I look?

Face to the west during late evening twilight, which is about 8 p.m. once Daylight Saving Time begins. On March 12, a thin crescent Moon will be to the lower right of the comet. Pan-STARRS will shift towards the north (to the right as you face west) each night. This shift towards the north means that Pan-STARRS always sets soon after the Sun and is visible only during evening twilight. You will therefore need a clear, unobstructed horizon to the west when observing right at dusk. Note that by the time Pan-STARRS appears in our sky, it is already receding from the Sun, and thus getting a little dimmer each day. Most likely, Pan-STARRS will fade from view by April. How long can you follow it?

What should I look for?

Look for a fuzzy spot, not a single point of light. Observers south of the equator have reported the comet’s total brightness as a little brighter than the Big Dipper’s stars. However, the comet always appears low to the horizon and in twilight; the thicker atmosphere and brighter background will make it dimmer. While Pan-STARRS is visible, the Moon goes from crescent to full, which will dim the comet. Past comets, such as Hale-Bopp in 1997, have shown long, extended tails.

However, Australian observers in early March reported a compact appearance for the comet, with a tail visible only up to two or three degrees from the head of the comet. (Your fist held at arm’s length blocks 10 degrees.) This appearance concentrates more of the comet’s brightness in a small area of sky, making it easier to see a against a twilight sky. Comet tails have a fainter look, comparable in brightness to the Milky Way band. Binoculars may help you locate the tail if you can’t make it out with the naked eye in the twilight.

Will I ever see this again?

No one has ever seen Pan-STARRS before, and no one alive today will see Pan-STARRS again. By all indications, this comet has traveled from the Oort Cloud into the inner solar system for the first time ever. And once it’s gone, it won’t return for another 110,000 years. However, Pan-STARRS could be just the ‘warm-up act’ for a much bigger and brighter comet in November and December 2013 — comet ISON.

Comets are notoriously unpredictable, though; there’s no telling if ISON will meet expectations. It’s better to take advantage of clear skies forecast for this week and look for Pan-STARRS. When you see it, you’ll be looking at one of the oldest, most pristine objects of our solar system.