Editor’s Note: HMNS Collections Technician of Anthropology Anna Dean details the victimization of the Osage people depicted in the film adaptation of the bestselling novel Killers of the Flower Moon.

Killers of the Flower Moon directed by Martin Scorcese and starring Lily Gladstone, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Robert DeNiro tells the story of an Osage family who is targeted for their wealth through a series of attacks and murders. But how much of the story is true? And how did the Osage people become the wealthiest population in the world over the course of a few years?

Ancestrally, the Osage occupied land in what is now Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois. They first encountered Europeans when French trappers sailed downriver from then-French-owned Canada. They would later meet Lewis and Clark during their famous expedition, learning that the land they lived on had been purchased without their consultation or consent by the United States government. A member of Lewis and Clark’s expedition, Pierre Chouteau, was assigned by President Thomas Jefferson to finalize a treaty with the Osage reducing their territory by over 50 million acres in exchange for the establishment of federal trading posts on their remaining territory.

Over the next 60 years, the Osage would be compelled to sign 10 more treaties, reducing their land to a small strip of modern-day Kansas. After the Civil War, the US Government chose to renegotiate all agreements it had with Indigenous tribes. The Osage, fearful of continuing encroachments, struck an unusual deal with the government in 1870. They agreed to move yet again to Oklahoma Territory, abandoning their territory in Kansas and all rights to any future federal aid, in exchange for the ownership of their land outright, including all development, resource, and mineral rights. The US government, believing the land offered in the Northwest corner of Cherokee Country to be barren and not good for much beyond cattle grazing, agreed. But the land was rich with oil deposits of which even the Osage were unaware.

Oil was first discovered on Osage land in 1897. Even then, the Osage had to wait for old cattle leases to expire before they could start publicly auctioning drilling leases. The passage of the Dawes and Curtis Acts meant that the Osage could no longer hold their land in the community. They decided to allot their land based on tribal membership from the most recent census, which meant every Osage man, woman, and child received a 657-acre plot. Every Osage person was instantaneously a millionaire. White Americans began flocking to Osage country in the hopes of striking it rich after severely underbidding an Osage member for their land.

The place where these auctions were held became referred to locally as the ‘million-dollar elm’. In a half-hearted attempt to protect Osage interests, the US government passed a law instituting the guardianship system. Under this system, every Osage person would be assigned a non-Osage guardian and an attorney. These individuals would hold the Osage person’s estate in trust, and draw a yearly salary from that trust. They would manage their ward’s estate until they reached 25 years of age and were determined by a non-Osage judge competent to manage their own affairs. There were no requirements to become a guardian of an Osage person, and there was no limit to how many Osage people one could be a guardian of. Almost immediately, the guardianship system became inundated with embezzlement, corruption, and crime. Guardians would convince their wards to make them inheritors in their will, or to take out large life insurance policies with their guardian as sole beneficiary.

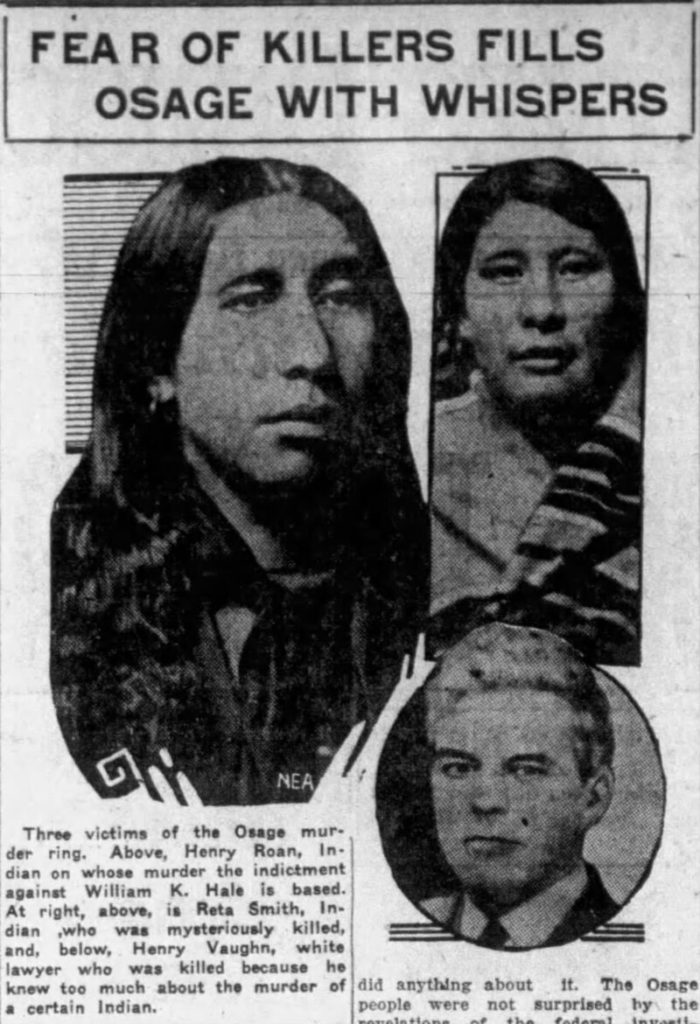

Osage people began to die much more frequently in Oklahoma, often just before reaching the age of majority and taking over their own estate. These deaths were often blamed on consuming ‘poisoned alcohol’ a term used to describe wood grain alcohol that was passed off as whiskey during Prohibition. Eventually, these murders became more brazen, and beginning in 1921 members of one extended family group began to die in conspicuous ways. Following the nitroglycerine bombing of Rita and Bob Smith’s home and their subsequent deaths as well as pleas for help from local and state police officials, the US Government sent representatives from the recently formed FBI to investigate the murders. What they uncovered was a huge inheritance fraud scheme and underground industries for hitman, poisoners, and the like.

William Hale, a cattle rancher, had employed his two nephews, Ernest and Bryan Burkhart as well as a string of petty criminals and drifters to murder Osage landholders, inheriting their estates in a complicated web of intermarriage and adoption. Many of the conspirators died under suspicious circumstances before being able to testify or serve time for their offenses. Hale spent 18 years in prison for his role as the ringleader of the plot.

Shortly after the trials, the US Government passed yet another law forbidding any non-Osage person from inheriting an Osage individual’s estate, thereby removing some of the motives for many of the killings that had taken place over the past 15 years. However, while the family central to the film Killers of the Flower Moon suffered greatly during what would come to be known as the Osage Reign of Terror, they were far from their only victims. While it is unknown how many were killed, at least 60 Osage people were reported murdered from 1918 – 1931, with no killer ever arrested. In 2011, the Osage Nation sued the US Government for the money embezzled from Osage people under the guardian system, caused by the government’s lack of oversight and neglect of the system. They were awarded $380 million. Over a quarter of Osage land mineral rights are held by non-Osage entities today.

The Houston Museum of Natural Science is proud to display items on loan from the descendants of the Wagoshe family, who lived in Osage Country while the events of Killers of the Flower Moon took place. You can learn their story, and more about Indigenous peoples across the United States, at the John P. McGovern Hall of the Americas.

More Indigenous stories

Indigenous Cowboys: The Living History of Native Americans in Rodeo