The stale sticky days of high summer are upon Houston – and also Egypt (although the Egyptian summer has stayed mild so far). What time of year could feel less fresh? For the Egyptians, however, now was the start of the year, a time of new beginnings.

Egypt, as no Egyptologist can avoid telling you, is ‘the gift of the Nile.’ Every year, heavy rains in the Ethiopian highlands swell the Blue Nile, carrying water and fertile silt downstream. The Nile flood, which Egyptologists usually call the inundation, is Egypt’s annual detox, as stagnant water and accumulated salts are washed out to sea. In addition, new fertile silt is laid down on the floodplain and farmers corral water into irrigation lagoons for the dry seasons that follow – no rainy season (or hurricane season) in Egypt. The reliability of the inundation allowed the Egyptians to build up surpluses to endure bad years, as shown by Joseph’s interpretation of Pharaoh’s dream in the Bible.

The Nile began to rise in June, with the inundation beginning in earnest in mid-late July and carrying on until October or November. At Aswan, on the southern border of Egypt, a Nilometer – a well with graded scales inside – allowed engineers to measure the Nile’s rise and predict whether the flood would be good or bad. A rise of sixteen cubits (approximately 8m26ft) was meant to be the ideal. As the waters receded, crops were planted, cultivated, and then harvested. Irrigation ponds – like the ponds and presas you see on ranches in Texas – could sometimes stretch the growing season out to produce two or more crops.

The rhythm of the Nile flood shaped the Egyptian calendar, dividing the year into three seasons of four months: akhet (‘flood’) was followed by peret (‘growing’) and finally shemu (‘low water’ or ‘harvest’). The first day of the first month of akhet was the beginning of a new year – but since the Nile doesn’t begin its rise on precisely the same day every year, how could you fix it more precisely? The Egyptians turned to the stars. They noticed that Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky, had its heliacal rising – when it first becomes visible again before dawn after a period of time below the night horizon – at the latitude of the capital Memphis at the same time as the start of the inundation in mid-June.

In Western astronomy, Sirius is in the constellation Canis Major – the Great Dog – hence the English term ‘dog days’ for this time of year, and the French word ‘canicule’ for a summer heatwave. For the Egyptians, however, Sirius was the goddess Sopdet (‘the sharp one’, whom the Greeks called Sothis), and the herald of the life-giving inundation. As the heliacal rising of Sirius was fixed every year, this became the starting point for the Egyptian ‘Sothic’ calendar.

The New Year (the ‘Opening of the Year’) was a popular festival in pharaonic Egypt, and other festivals, notably the Opet festival in the southern city of Thebes (modern Luxor) livened up other months of akhet. You might think that with the waters of the inundation covering the fields, the farmers of Egypt had a lot of time spare to enjoy themselves during akhet, but no such luck. It’s generally held that they were liable to be pressed into service for state works during the inundation, namely building pyramids and any other construction projects Pharaoh had in his in tray. The extent of this practice is uncertain: in the 19th century AD, however, when Egyptology was formed as a discipline, Egypt’s rulers relied on this unpaid labour (called corvée) to build the Suez Canal, Egypt’s railways, and other state projects. The assumption has stuck with us that, then as now, corvée was a vital part of the Egyptian state.

So: in theory, Sirius rose on the first day of the first month of akhet. In practice, though, this soon unravelled. Not only does the rising of Sirius move forward a day every 120-ish years (this, combined with the fact that the current Gregorian calendar is thirteen days ahead of the Julian calendar means that Sirius will rise in Houston around August 3rd or so, but a calendar of 365 days without a leap year will lose a day every 4 years. After a century of this, Sirius rises almost a month askew from the calendar, and only returns to its original position after 1460 years, the so-called Sothic cycle. To cap it all, the ancient Egyptians recorded their dates not from a fixed point (well, we have to admit it would have been hard for them to count backwards using BC, even though it would have been very convenient for us) but according to the reign of the current king. These are all reasons why I try to duck questions on Egyptian astronomy, calendars, and chronology. A good introduction to the topic, after Wikipedia, is R. A. Parker’s classic The Calendars of Ancient Egypt. Be that as it may, the annual rising of the Nile in midsummer was anxiously awaited and celebrated by the pharaohs and their successors.

The building of the Aswan High Dam in the 1960s ended the inundation in Egypt, severing a link between man and environment that had nurtured one of the world’s great early cultures. The Nile still waters the fields of Egypt, but is now dispensed throughout the year through the Dam’s sluices. Egypt needs the Nile more than ever to support its growing population, and the recent completion of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) has raised fears for the country’s water security.

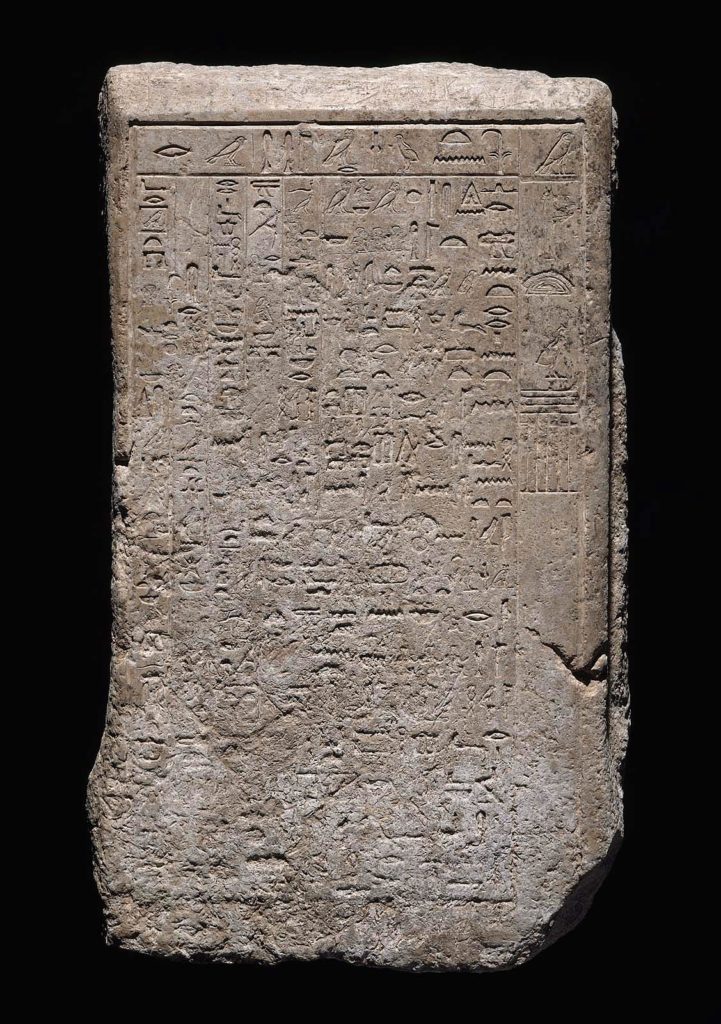

But where does the museum come into this? Well, in the Hall of Ancient Egypt you can see an object inscribed with a date, a royal decree from about 2475 BC, where the rather worn last line (you might need to visit it and bring a torch to get some raking light to be extra sure) gives a date in the season of shemu. We also have a couple of ancient New Year souvenirs.

The New Year was celebrated with gifts of perfumes and the fresh water of the inundation, housed in so-called ‘pilgrim flasks’, round bodied vessels with a thin neck with a rim in the form of a lotus or papyrus flower. These ‘New Year’s bottles’ are made of green glazed faience, a colour that would remind people of the fresh crops that would come after the inundation.

The inscription on the seam of the bottle is the usual one for these objects: “May the god Ptah open a beautiful New Year for the owner [of this bottle]”. You can see the same inscription running down the front of our other New Year’s bottle:

And if you can’t make it to the museum, you can get some idea of the ‘materiality’ (archaeological #buzzword alert) of these things by checking out this model of a New Year’s flask excavated recently.

The idea of starting 2020 all over again with a clean slate is pretty tempting. Perhaps a swig of Nile water and the blessing of Ptah might be a classier – and luckier – way to ring in the New Year than our own traditions…