It’s been hard to avoid the online memes and gags about hairdos in the time of corona. Have you let it all go wild, or taken matters into your own hands? As it happens, something in the Hall of Ancient Egypt reminds us that the Egyptians had hair concerns of their own. And, as today, these hair styles aren’t just about looking good, they have practical and social dimensions too.

Halfway down the long pillared room in the Hall of Ancient Egypt, on the right hand side, we’ve always had a case with sculptures depicting Egyptians (and their hairdos) in relief and statuettes. I brought the objects together in the case to try to show how artists dealt with the same basic commission – show a well-to-do person – in 2-D and 3-D, and how the conventions of Egyptian Art varied between them.

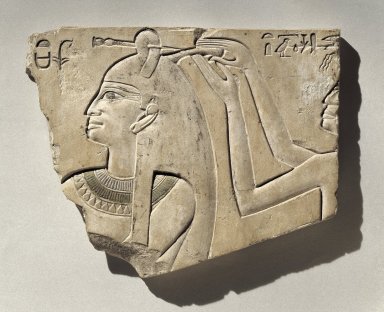

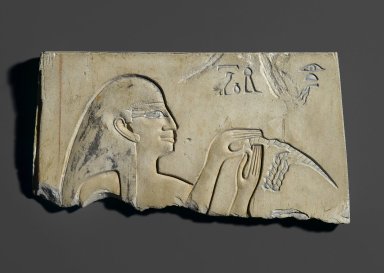

I liked juxtaposing relief and sculpture of women from the late 18th Dynasty (about 1330 BC, around the reign of Tutankhamun). Both the limestone relief of offerers, on loan from the Roemer und Pelizaeus Museum, Hildesheim, and the rather worn steatite bust, from Chiddingstone Castle in the UK, show women wearing floating pleated linen dresses and elaborately braided hair.

Big hair was the rage at this period for men and women. Children were shown with scalps shaven, save for a braided ‘sidelock of youth,’ and growing your hair out may have been a marker of entry to adulthood. Certainly good hair was a marker of sexual attractiveness and availability. One of the world’s oldest pick-up lines, from the Tale of the Two Brothers, around 1100 BC, can be loosely translated as ‘fix your hair and let’s have a good time’, and specific hairstyles linked women to goddesses of fertility like Hathor (sometimes called ‘Lady of the beautiful hair’).

For the well to do, most hairpieces were wigs, usually made of human hair, sometimes bulked out with plant or animal fibres. They could be put on for special occasions, and taken off when not needed. In somewhere as hot as Egypt, there’s a lot to be said for being able to take off your wig and cool down when you’re not on show. Many men routinely shaved their heads and wore wigs, not just to keep cool and fashionable, but also to fulfil requirements for purity – but that’s another topic for another blog post…

Recent excavations at the city of Tell el Amarna, where Tutankhamun grew up, have brought to light a cemetery of the less well to do, revealing a wide range of actual hairdos including braids, extensions, dye-jobs, and childrens’ sidelocks – a reminder that sculpture and carvings really were translating ephemeral fashions into eternal representations.

Back in the Museum, the case has now been graced by some new arrivals that show how the Egyptians actually dealt with their hair in the New Kingdom, about 3,300 years ago.

Top left, a copper alloy razor of a type both men and women used to shave. Blades were cast, hammered to a cutting edge, and kept sharp (well, sharp-ish – I haven’t heard of any Egyptologists shaving with a replica, and am not going to volunteer) with a whetstone. You might just be able to see, in the pattern of the corrosion on the surface, the ‘ghost’ of the cloth that wrapped the razor when it was buried, as well as the shining golden surface of the pristine metal.

Bottom right, a fragment of a wooden comb to keep hair free from tangles. Like today, Egyptian combs had different spacing of teeth for different purposes, and one of those – just like today – was to comb lice out of the hair.

At the top, a wooden hairpin with a decorated top, to gather hair together. A tomb scene from the Middle Kingdom in Brooklyn Museum shows a similar one in operation:

Centre bottom, a plait of human hair. It’s impossible to know if this is one that has come loose from a wig, or is an individual extension, like this representation from the same tomb:

In the centre of the board is a red jasper penannular (‘almost a complete circle’) ring, which could have been twisted into the hair.

Bottom right are two triangular inlays, mold-made of blue-glazed faience. These are depictions of tightly curled hair, and probably came from a prestigious coffin showing the dead person in the costume of daily life, his (or her) wig modelled with great care and turned into a shining blue mane. The Egyptians expressed the awe in which they held the divine by imagining the gods were made out of the most precious materials they knew of. The gods’ bones were silver, their skin gold, and the hair of the gods was the precious blue stone lapis lazuli: when you died and united with Osiris, god of the dead, your body would be transfigured into divine materials. These faience curls show this belief turned into reality.

The final piece on the board is centre right: an implement made of two pieces of copper alloy riveted together.

The shorter end has two pointed tips, one of which fits neatly into the curved section of the other. The other end has a long pointed tip, and another which terminates in a flat teardrop-shaped end with sharpened edges.

These objects are as unusual as they are rare – a colleague has listed around 30 of them in museums worldwide. When they have been formally excavated, they come from New Kingdom contexts, linked to cosmetics, but many are only known from the art market. Instead of being plain, as on ours, the handles can also be decorated. One particularly glamorous example in the Metropolitan Museum is made of gold, but most are copper alloy.

The precise function of these objects is still uncertain. They have been called curling tongs, or crimpers – but heating such small metal objects would make them too hot to hold. Eyelash curlers? But the way the elements are joined together means you have to push the ends apart to close the other end, rather than being able to squeeze them closed, which also seems awkward. And what about the small sharp blade on the longer end? We dodged a bullet and called it an ‘implement’ on the label, which doesn’t really get us very far.

Most Egyptologists roll their eyes whenever they hear people talking about Egypt’s ‘lost secrets’, but these objects really are a mystery, however minor, of Egyptian culture, and the field is open for an assessment of these unusual pieces. All suggestions welcome!