Editor’s Note: HMNS Curator of the Hall of Ancient Egypt gives an insider’s look into a newly loaned piece on display.

A new loan in the Hall of Ancient Egypt is an arresting reminder of the fact that Westerners have been making myths (and fun) of Pharaonic Egypt for a very long time.

Paul Marie Lenoir

Oil on canvas, 1872

Nineteenth century artists mined ancient history for anecdotes they could transform into eye-catching artworks. For his work Cambyses at Pelusium, now on view in our Hall of Ancient Egypt, French artist Paul Marie Lenoir (1843-1881) took an account from the Stratagems of Polyaenus (written around 160 AD) about the conquest of Egypt by the Persian king Cambyses in 525 BC.

When Cambyses attacked Pelusium, which guarded the entrance into Egypt, the Egyptians defended it with great resolution. They advanced formidable engines against the besiegers, hurled missiles and stones and fired at them from their catapults. To counter this destructive barrage, Cambyses ranged before his front line, dogs, sheep, cats, ibises and whatever other animals the Egyptians held sacred. The Egyptians immediately stopped their operations, out of fear of hurting the animals, which they hold in great veneration. Cambyses captured Pelusium, and thereby opened up for himself the route into Egypt.

Did the Egyptians really, honestly surrender rather than run the risk of killing animals they considered sacred? Polyaenus’s story is obviously untrue – the Egyptians were happy to sacrifice cats to mummify them so worshipers could buy them and offer them at shrines – but shows how, already in antiquity, Egyptian culture was associated with the irrational worship of animals. But did the story originate outside Egypt, as a neat encapsulation and dismissal of Egyptian customs, or were Egyptian storytellers in on the act, poking fun at themselves for foreign visitors? There is an echo in Polyaenus’ story of an earlier account of Cambyses’ conquest of Egypt. According to the Greek historian Herodotus (c. 430 BC), Cambyses himself killed the Egyptians’ sacred Apis bull, the incarnation of the God Ptah, stabbing it in the haunch with his own dagger to show how powerless and weak the gods of the Egyptians were.

Joseph Bonomi

Pencil, c. 1840s?

© The Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

Reproduced with permission of the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

Shortly afterwards, however, Cambyses leaves Egypt to put down a rebellion in Persia. Mounting his horse, his scabbard breaks and his dagger wounds him in the thigh in the same place as he had stabbed the Apis. He later dies of gangrene. The Apis had taken revenge. In fact, while an Apis bull did die in the reign of Cambyses, its burial stela survives and shows Cambyses himself offering in its honor. Herodotus’ story is – like that of Polyaenus – too good to be true. Scholars have suggested that the story of Cambyses’ death, perhaps the first literary example of the curse of the pharaohs (well, of the Egyptian gods), combines Egyptian and Persian motifs to disparage his reputation, as Cambyses was also denounced by his successors on the Persian throne who also had an interest in discrediting him.

Dramatic stories like these were the bread and butter of 19th century Academic art, giving viewers a stirring dose of sex and violence under a fig leaf of historical education. The classical and medieval worlds were the most usual source of topics for historical paintings, but Egyptian culture and mythology also provided a respectable number of subjects. These were given a spurious accuracy and immediacy by the scrupulous copying of objects in museums in Europe and temples and tombs in Egypt. Mesopotamian topics were much rarer, in part because there were fewer models to follow.

Gypsum (‘Mosul Marble’),

From Nineveh, modern Iraq, c. 645-635 BC

Image courtesy The British Museum

Gypsum (‘Mosul Marble’),

From Nineveh, modern Iraq, c. 645-635 BC

Image courtesy The British Museum

For Lenoir, Polyaenus’s story gave him an opportunity to show off his research and powers of observation. The clothes worn by Cambyses and the trappings of his horses are copied from Assyrian reliefs of about 120 years earlier. Lenoir had visited Egypt a little before he painted Cambyses at Pelusium, and his facetious travelogue The Fayoum, Or, Artists in Egypt states that “Our object in going to Egypt was to look out for subjects for pictures, and to paint them”. Ironically, the Egyptian ‘Hathoric’ (cow-goddess-headed) columns of Pelusium are based on those at the temple of Dendera, which Lenoir didn’t visit on that trip. He must have relied on photographs of Dendera for this – there was no shortage of these even in 1872. Lenoir could have purchased them in Cairo or back in Paris.

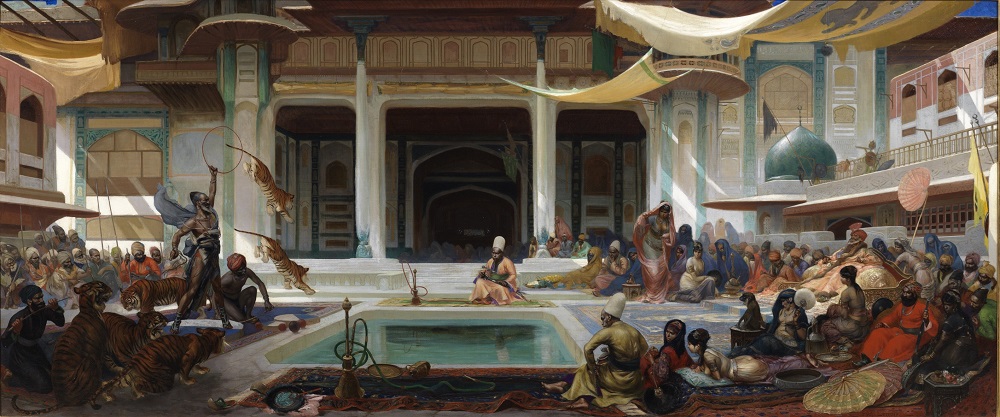

Lenoir took obvious pride in showing the twisting bodies of the unfortunate cats, and these vividly suggest a lot of experimentation. A later painting of Lenoir’s, The Pacha’s Entertainment, depicts tigers leaping through hoops to amuse a jaded ‘eastern’ potentate and his court. Lenoir obviously had a thing about felines in motion.

Paul-Marie Lenoir

Oil on canvas,

Image courtesy of The Mathaf Gallery, London

Cambyses at Pelusium was accepted at the 1873 Paris Salon, the French art world’s ground zero and was praised by critics. One said, “This isn’t just a learned painting, but a very charming one.” Another concluded, “It is a shame that the nineteenth century doesn’t use similar tactics. It would be cheaper and less damaging than shells, and in the evening after you’ve won you can turn the missiles into kebabs.”

Lenoir’s painting soon left Paris for the deeper purses of the United States. By 1880 it had entered the collection of railroad magnate Charles Crocker in his mansion in San Francisco’s Nob Hill neighborhood. Crocker’s collection was one of many described by Edward Strahan, in his lavishly produced series The Art Treasures of America. Both Cambyses and its owner got a flattering write up from Strahan:

Mr.Crocker’s personal explanations, delivered in a happy vein of reminiscence and cosmopolitanism, considerably increased my interest in his gallery. He compared the long bastion of Pelusium, in Lenoir’s “Cambyses,” with the equally long and exposed citadel-wall of the great fort at Cairo, where the massacre of the Mamelukes took place, and where he had wandered, and measured, and paced, to his heart’s content as an insatiable American tourist. He was kind enough to be interested in my personal reminiscences of Lenoir, certainly one of the most cultured and witty of modern painters, the powers of whose mind undoubtedly culminated in the “Cambyses.”

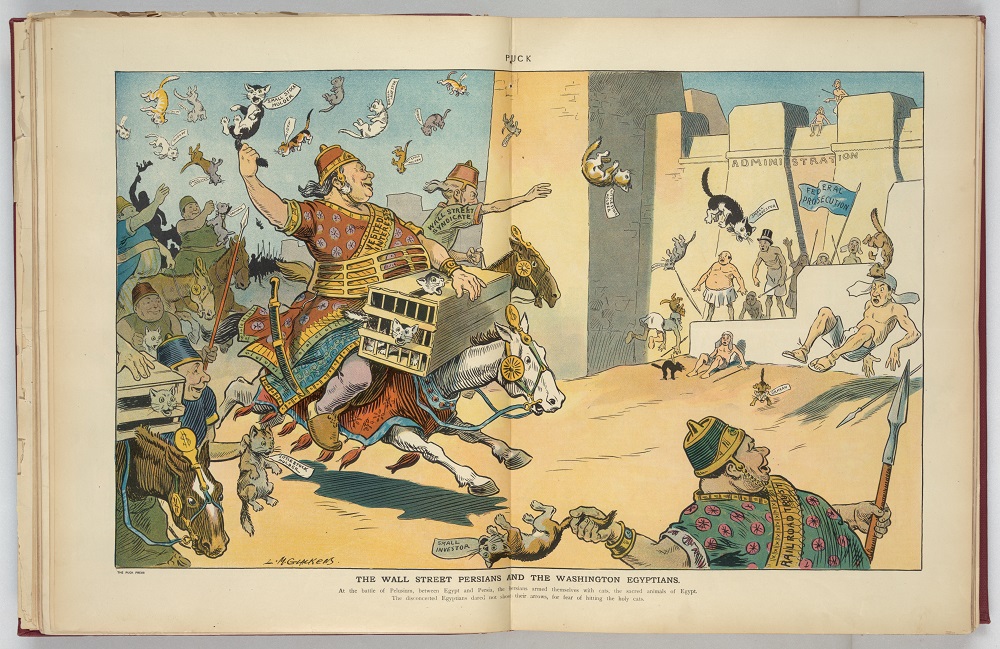

Cambyses at Pelusium also got a photogravure plate in the volume, which ensured that it would reach a wide audience through reproduction and redistribution. At one point, prints of Cambyses must have adorned houses throughout the United States, since it was a familiar enough image to be used as the basis of a cartoon in the satirical magazine Puck, at the start of the Bankers’ Panic of 1907.

L. M. Glackens

Color print, Puck, 27 March 1907

Image from the Library of Congress

The ‘Wall Street Persians’ – one, like Charles Crocker, personifying a railroad trust – hurl cats labelled ‘small investor’ at the terrified ‘Egyptians’ representing the federal administration. Lenoir’s painting is copied to make an erudite point about Big Money operating with impunity.

Paintings like Cambyses at Pelusium – and many others illustrated by Strahan in his survey of Gilded Age collections – fell from favour around 1910, as wealthy collectors turned from 19th century Academic painters like Lenoir to the Old Masters and, later, the Impressionists. Works that had fetched top dollar in 1880 barely sold for the cost of their frames in 1950. Fashions have changed again, however, and Academic and Orientalist paintings are now eagerly collected, their many fine qualities (admittedly, restraint is usually not one of them) appreciated once more.

The only thing that could make Cambyses at Pelusium even better, in my opinion, would be movement. Those poor plummeting cats are just crying out (meowing out?) for animation, and our talented team has worked its magic on the picture. Enjoy!

Visit the Hall of Ancient Egypt today and see Cambyses at Pelusium up-close as a part of our permanent exhibits collection. Members receive free admission to the permanent exhibits all year long! Learn more about membership here.