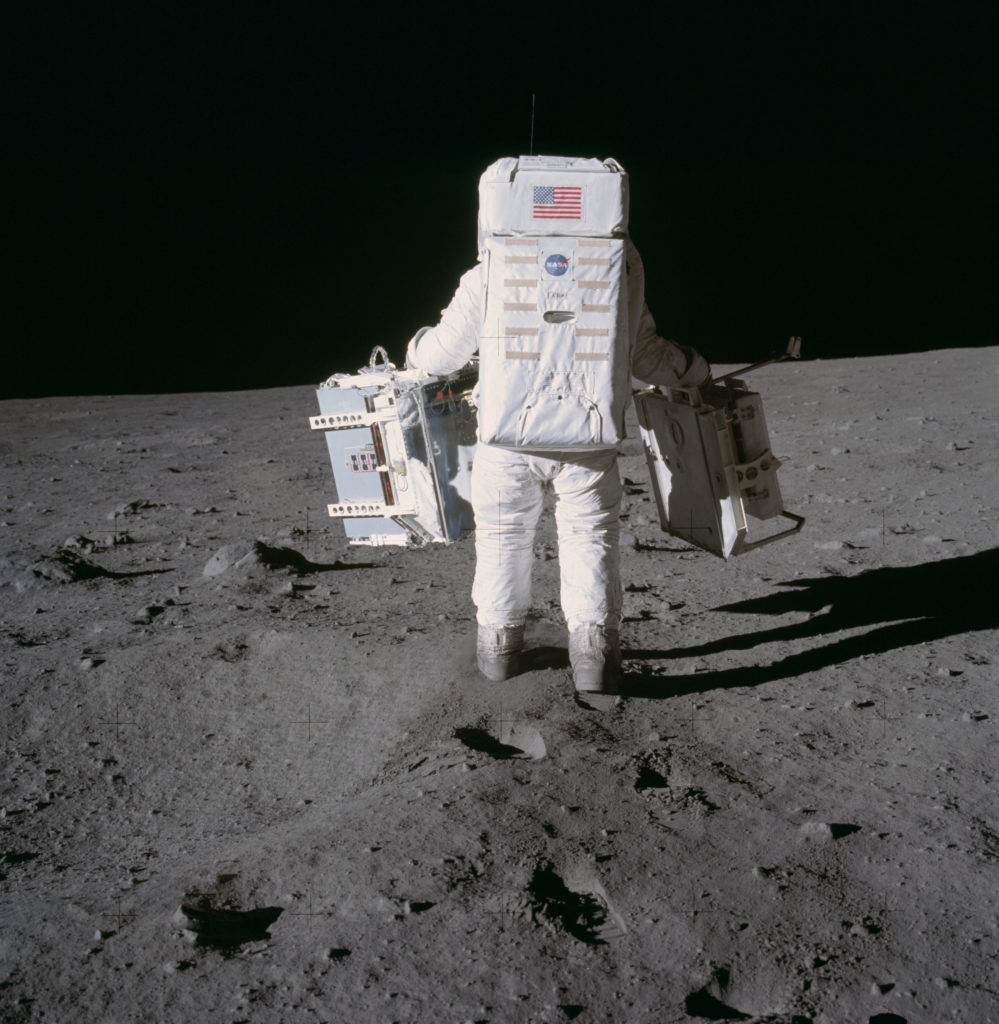

The city of Houston had already firmly grasped its place in history as “Space City” by the time Apollo 11 launched from Cape Kennedy on July 16, 1969.

The Houston Astros played inside the Astrodome, Judge Roy Hofheinz’s man-made UFO just south of the Texas Medical Center. Sweaty kids acted out otherworldly adventures in plastic spaceman helmets while their fathers and mothers chain-smoked at desks at Clear Lake’s Manned Spaceflight Center while fidgeting with slide rules. Advertisements of the day were full of streamlined space-age imagery, from car dealerships to natural science museums and burger joints.

(PHOTO: Bill Wilson-flickr)

Humans were heading towards the moon and Houston was along for the ride.

Some of the staffers here at the Houston Museum of Natural Science were scattered across the globe but united under the same moon.

Dr. Carolyn Sumners was tubing down a river in Arizona as Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins were gracefully hurtling moonward. One would think that the future astronomer extraordinaire would be watching the moon landing with bated breath alongside dozens of her fellow interns at the Kitt Peak National Observatory but she was inside an inner tube.

“We stopped to eat and watch the first images from the moon,” Sumners recalls.

Although these days we look back on the event with a sense of awe and inspiration, Sumners remembers trepidation in the scientific community.

“I remember how worried the scientists were that the astronauts would sink into the lunar regolith. We really didn’t know its surface characteristics,” Sumners says. “With no atmosphere and no wind, there’s nothing to disturb the surface material and give us clues about the depth of the dust.”

In less than a year, in June 1970, Sumners would join the staff at the museum in Houston.

“I guess that after the landing I was more excited about coming to Houston,” she says.

Meanwhile in Shaker Heights––just outside of Cleveland, Ohio — a young Lisa Rebori was in front of a black-and- white Zenith set in her family’s living room with her entire family watching history unfold. The future VP of collections and exhibitions at HMNS remembers staring at the TV set as the astronauts made sense of the light- ness of the weightless environment.

“The footage was so grainy, the curtains in the room were drawn so that we could see the images better. I remember it seemed to take forever from the landing until they opened the hatch and Neil Armstrong emerged,” Rebori says.

Even as a small girl she knew that she was entering a new era.

“It was such an amazing achievement of engineering, creativity and will power. It was a patriotic moment when the flag was set, the American work ethic at its best. Dream it, set your mind to it, head down, work hard and your dreams could come true.”

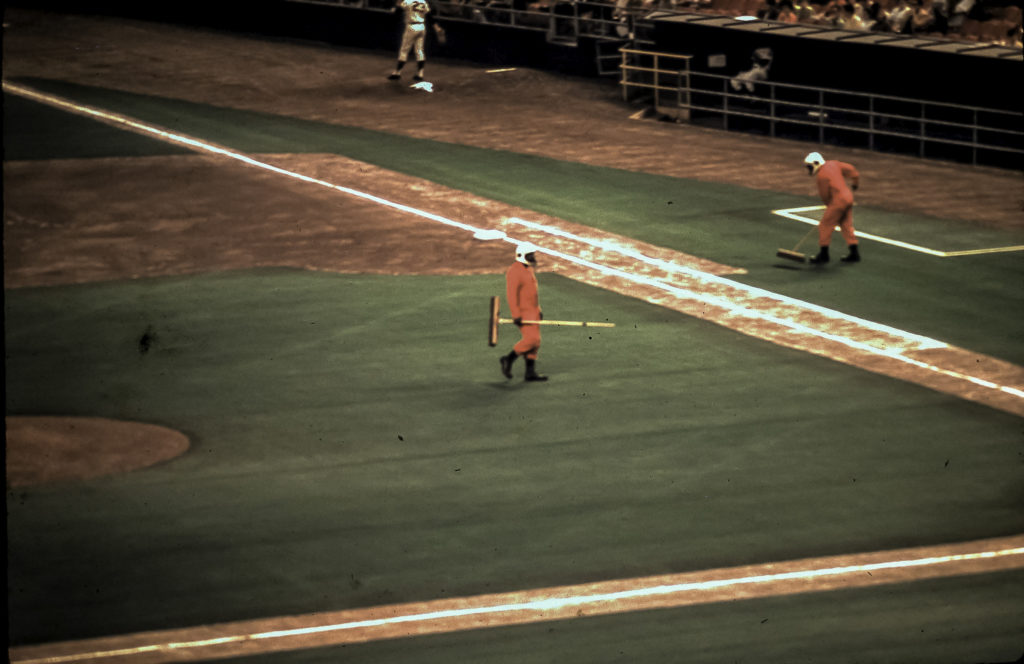

While little Lisa Rebori was able to get newsman Walter Cronkite’s play-by-play of the events unfolding on the moon, ZZ Top’s Billy F. Gibbons learned from none other than guitar legend B.B. King that men had landed on the moon.

Gibbons was among a few thousand Houston rockers in attendance at the touring Longhorn Jazz Festival at the now-demolished Sam Houston Coliseum the night that Apollo 11 entered history.

The bill also included Miles Davis, Nina Simone, and Blood, Sweat and Tears.

At around 10 p.m. that night King stepped away from the blues for a bit to fill in his audience on what was happening thousands of miles from the venue.

“B.B. King took a momentary sidestep to share the moon landing announcement with the audience in the midst of the rousing entertainment gathering in Space City,” Gibbons says. “To say the least, that was quite a fitting setting in which to hear the news.”

The fact that humanity had forever changed that night seemed to have lifted the venue up a few inches in the air.

“The show resumed with a spirited ‘lofty’ uplift for the remainder of the night,” he adds. “It was a memorable place in time to hear of such a wondrous event.”

Looking back at Apollo era now, for all its wonder and magic, it didn’t last all that long.

Sumners says that in 2019 it’s easy to overlook the cramped timeline that put men on the Moon. Apollo 8 orbited the moon at the end of 1968, followed by Apollo 10 in May 1969. Two months later we had an American flag planted inside the lunar soil. By December 1972’s Apollo 17 were seemingly tired of lunar roving.

“We thought we could go anywhere we wanted in the solar system,” Sumners laments. “We can’t do anything this fast now. But then it seemed so easy and with almost no computer power.”

In this age of social media it’s hard to imagine something like a moon landing not being the only game on Earth.

Future curator of anthropology Dr. Dirk Van Tuerenhout was a ten-year-old on family vacation in eastern Belgium on July 20, 1969.

“The place we were staying at had one large room set aside for TV watching. I remember walking by that room and seeing the images of what I later realized must have been the Moon landing,” he says. “We kept walking back to our bungalow because I guess it was close to our bedtime.”

Van Tuerenhout says that the enormity of what he witnessed in those seconds didn’t sink in until sometime later.

“I was busy running around with my friends in the woods and going swimming. Electronic media was a whole lot less intrusive then,” he says.

Way out in Rockdale – halfway between Round Rock and College Station – an eleven-year-old Lyle Lovett was watching the landing in front of a television at his great-aunt Marie’s house.

He says that the adults around him didn’t seem to believe what they were witnessing. People who lived through world wars and the Great Depression couldn’t believe their eyes.

“There was a feeling of fulfillment. They were all watching intently, quietly amazed,” Lovett says.

Years before he would hit singer-songwriter stardom and become a household name Lovett was a regular at HMNS coming in from the Klein area. His mom and dad worked off Fannin giving him optimal proximity to the museum and the Houston Zoo as a boy. He remembers the Burke Baker Planetarium giving him a special thrill.

“Growing up in Houston everything was about the space program. As a boy I certainly connected all those dots. The Astros logo, the Astrodome itself,” Lovett says.

Houston artist David Adickes, known for his large-scale sculptures that dot our concrete-laden landscape, wasn’t even in Houston when men landed on the Moon.

(photo: JaseMan – Flickr)

“At the time of the Apollo 11 mission I was in France with my wife and I didn’t even have a TV,” Adickes says. “We were living there at the time but I do remember everyone was excited over it.”

He says he did feel pride over his hometown playing a major role in such a historic event. He had come to Houston proper in the early 1950s.

Houston in 1969 was a wildly-varied place, Adickes says. At the time Adickes was still just making a living by painting pictures for his dedicated patrons in the local art world.

“Houston was a high energy place even in the late 1960s, much like it is now,” Adickes says. “People got along better than they do now though.”

Jackie Fountain celebrated her 26th birthday on July 20, 1969 so her present was seeing Americans toddle around on a distant natural satellite.

These days she’s a volunteer at HMNS’ Sugar Land campus but 50 years ago she was raising two youngsters at home. She remembers going out and showing her 4-year-old son the Moon out in the Texas sky.

“We pointed to the Moon telling him that the men he was watching on TV were really on the Moon up in the sky,” Fountain says. “I remember reading comic books as a child about Martians and now men were walking on the moon.”

A sense of science fiction becoming science fact washed over the world it seems. Although there was an American flag stitched on the suits worn by those astronauts looking down at us, it was a global win.