Worldwide shortages of helium are sparking heavy concerns that the noble gas may soon be too scarce to fill our balloons or even provide it’s vital cooling properties to the MRI’s that so many health providers depend on to save lives. In today’s edition of Beyond Bones we’re going to discuss how we got ourselves into this situation and try to look for a light at the end of this deflating bounce house tunnel.

First off, let’s address the severity of the situation. In reality things are not as bad as many news outlets make them seem. The helium shortages are due more to government action than to an actual absence of helium. In reality there’s enough helium trapped underground to provide for humanity’s needs for generations to come. The problem is that for more than fifty years the U.S. government has kept a massive stockpile of helium which has acted as a reliable safety net for the helium industry. Now Congress wants to get out of the helium business, and private companies are struggling to expand their production to meet demand.

The United States is home to the largest helium reserves in the world, the most important of which extend from the Texas panhandle up through Kansas. These reserves are not pure helium, but rather natural gas deposits with an unusually high percentage of helium in them, up to 1.9 percent. They were discovered in the 1890’s, but they were not considered valuable until World War I.

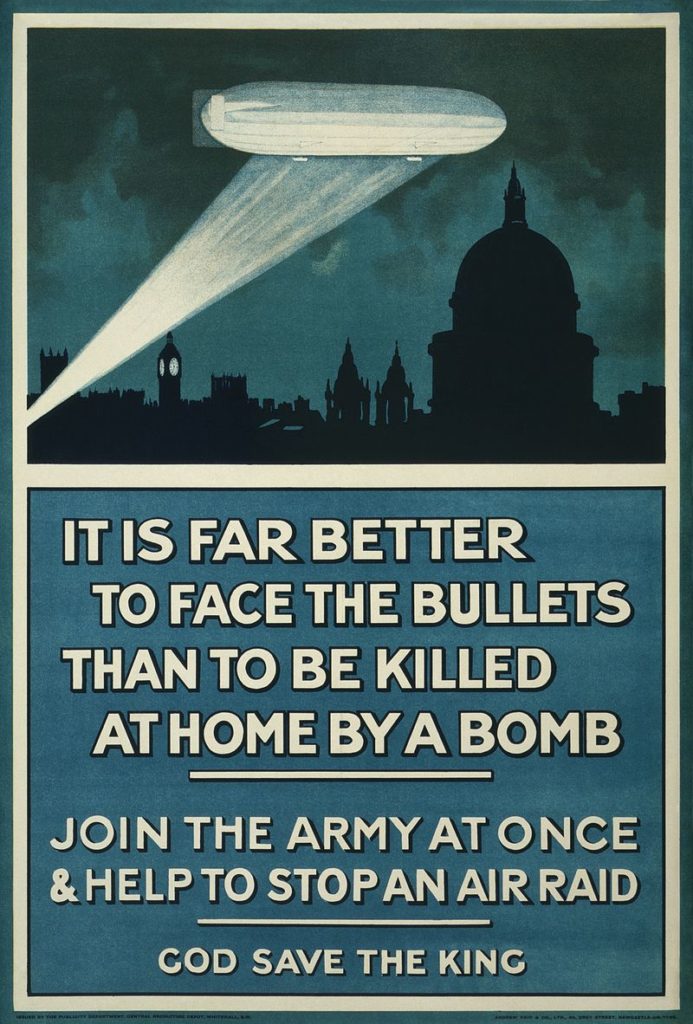

During the early 20th century, aeronautics was in its infancy and airplanes of the era were small and only capable of short flights. Lighter than air ships (“Zeppelins“) on the other hand could travel vast distances at relatively high speeds. Inspired by the Germans, who used air ships to bomb London and also scout battlefields, the U.S. military envisioned a fleet of Zeppelins, including floating aircraft carriers that could carry a force of biplanes anywhere in the world. This is where the story of the U.S.’s helium obsession begins. Unfortunately, by the time World War I ended they had only refined enough helium to fill one small airship.

British First World War poster of a Zeppelin above London at night. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

But the military wasn’t deterred and after the war they invested more money into helium research. The U.S.’s helium deposits were considered a strategic resource and in 1925 Congress passed a helium embargo on the entire world, fearing that if other nations had easy access to the gas they would develop superior aircraft. Because the U.S. practically controlled the world’s helium supply (we are home to 75% of the world’s helium reserves) other nations were forced to use hydrogen in their lighter than air ships.

Hydrogen, of course, is extremely flammable and over the years several hydrogen-related Zeppelin disasters fueled resentment against the U.S. for hoarding the valuable resource. This all culminated in 1937, when the Hindenburg exploded. There was so much backlash at the U.S. for withholding its helium that Congress considered lifting the embargo, before changing its mind over concerns about how the Nazis would benefit from access to the gas.

After World War II, the government’s attention focused less on keeping helium from other nations and more on creating a stockpile within the U.S.’s borders to ensure a steady supply of helium in the future. In the early 1960’s, the U.S. Bureau of Mines contracted five private refineries to recover helium from natural gas production, making them the largest producer of helium in the world. That helium was then transported by pipeline to a giant underground reservoir called the Bush Dome, near Amarillo, Texas.

The reason for the U.S.’s interest in stockpiling helium was the space race. One of helium’s most important qualities is that it boils at an extremely low temperature, so liquid helium was used as a coolant for satellite instruments and to keep the liquid oxygen and hydrogen fuel that powered the Apollo space vehicles cool. The Government feared that if helium reserves ran low in the future, it would affect the development of space travel, so they hoarded as much helium as they could.

A Saturn IB rocket launches Apollo 7, 1968. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

By 1990, this “Rainy day” helium cache had grown to a billion cubic meters, and in the process of collecting it the government had racked up more than a billion dollars in debt. At that point officials began to realize that nobody needs that much helium, so in response the Helium Privatization Act was passed in 1996. The act stated that the Bureau of Land Management, the organization that then maintained the helium stockpile, needed to shut down the stockpile and sell off its reserves by 2015. And that’s what they did. They sold off helium at below market price so that by 2015 the government could pull out of the helium business and private companies could take over and sell competitively.

The problem was that since there had been a reliable source of helium coming from the Bush Dome for so long, the industry had become dependent on the safety net it provided. There were not enough private companies set up to refine helium. And after the 1996 Privatization act was passed, with the government selling off cheap helium at prices nobody could compete with, there wasn’t any money to be made in helium, so nobody invested in setting up new wells or refineries. As we got closer to the closing date for the helium reserve, there was nobody there to pick up the slack and keep up with the world’s demand for helium. Fast forward to the late 2000’s and as the government prepared to shut down its stockpile, private production hadn’t caught up, thus the helium shortages began.

In 2013 the House of representatives voted to extend the life of the reserve under government control in response to periodic shortages, but until the private helium industry takes off, we can expect unpredictable shortages and price jumps.

One of the big issues with helium is that it is a byproduct of natural gas production. That’s why the government stockpiled it for so long. They didn’t want to waste the helium coming out of natural gas wells, but they didn’t want to sell it either. Big companies aren’t going to shut down natural gas production to conserve helium, and they aren’t going to ramp up natural gas production to extract more helium, since the noble gas is ultimately a byproduct whose profits are small potatoes compared to natural gas. So it’s a weird situation, especially since most natural gas deposits only have a tiny fraction of helium in them.

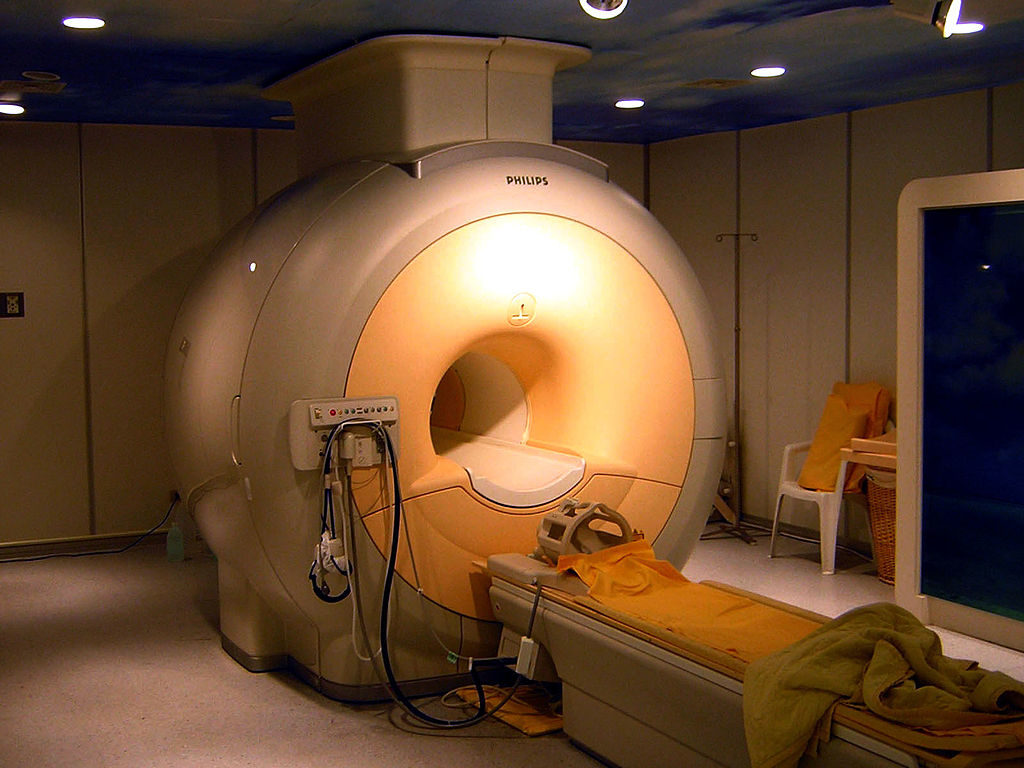

The largest single use of liquid helium is to cool the superconducting magnets in modern MRI scanners. Author: KasugaHuang Source: Wikimedia Commons.

There are currently companies exploring for more profitable helium reserves, and a good candidate was recently discovered in Tanzania. But it will take time for private companies to figure out how to profitably extract the gas. Until then, things will remain a little heavy. The hope is that progress will be made within the helium industry before these shortages start to affect hospitals and research laboratories. Helium is still an important coolant for many devices including MRI’s, which require their magnetic coils to be super cooled so they can create a strong magnetic field.