By Emma Boehme, Marketing Intern

This limestone wall carving which can be found in our Hall of Ancient Egypt depicts Nefertiti and her two daughters. The artifact seems normal at first glance; however, upon closer look you can see that the cartouche at the top left, which would usually contain the hieroglyphs for a pharaoh’s name, is scratched out and the legs of the two smaller figures seem to have been chipped away, not to mention Nefertiti’s missing body. So, why would someone deface this pharaonic work?

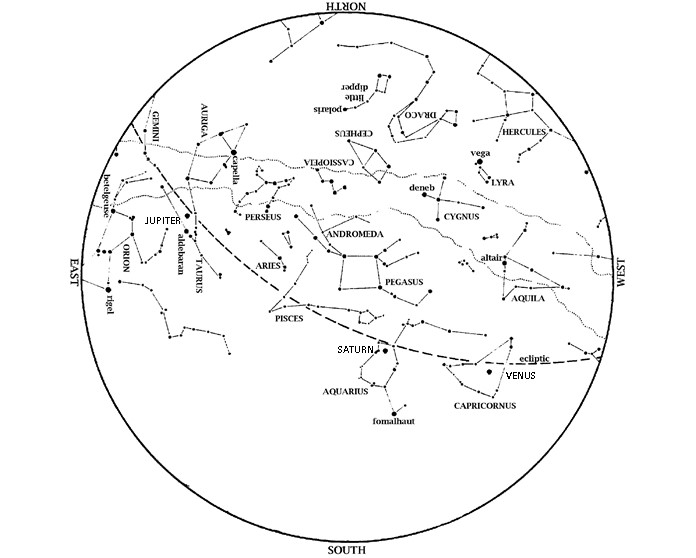

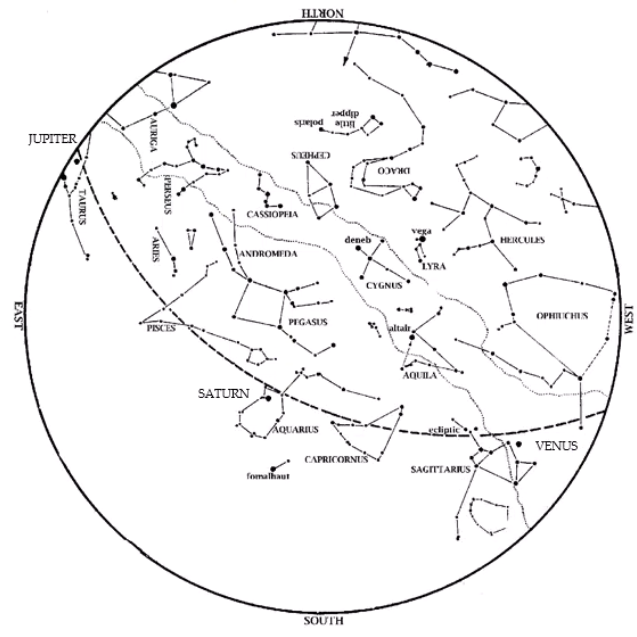

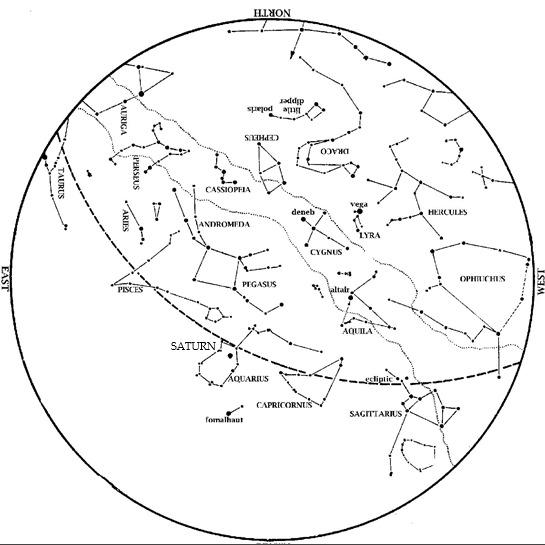

Nefertiti was the wife of Amenhotep IV, or as he later referred to himself, Akhenaten. His reign was very controversial because he drastically changed the art and culture of a nation which had been fairly homogenous since the reign of Narmer, almost 3,000 years prior. As pharaoh, he forced a society which believed in dozens of gods which each served different purposes to follow his quasi-monotheistic worship of Aten, the androgynous agender sun god. This is why he changed his name to Akhenaten, which directly translates to ‘beneficial to Aten”. A part of why Akhenaten’s reign is so odd is that, directly after his death, Egyptian art and religion reverted back to being the same as it had been for the 3,000+ years before Akhenaten.

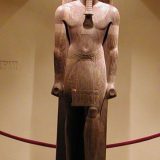

Not only did Akhenaten prompt a new religion, but he brought on a drastic change in art style, referred to as the Amarna Period by art historians. As you can see in the Ka statues of Amenhotep III (Akhenaten’s father, 18th dynasty), Khafre (4th Dynasty), and Hatshepsut (female pharaoh, 18th Dynasty), the three all carry their fists at their sides and their muscular bodies in rectilinear shapes. These characteristics follow the classic Egyptian style, displaying pharaohs as strong and powerful entities. During the Amarna Period However, Akhenaten replaced strong and powerful depictions of the pharaoh with androgynous, soft, curvilinear figures with elongated extremities and facial features, protruding lips and puffy eyes, as seen in his Ka statues and in the wall carving of him, Nefertiti, and their three children.

Some historians now suggest that these changes during the Amarna Period in both religion and art could be easily explained if Akhenaten was an individual with Marfan Syndrome. Marfan’s is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder which causes elongation of extremities and facial features, lack of tone,curvature of spine, and puffy lips and eyes; physical descriptors which align with depictions of Akhenaten. Unfortunately Akhenaten’s mummy has not been discovered, making it difficult to prove these assertions and many historians suggest that the change in art style merely represents a way that Akhenaten consciously distanced himself from artistic styles used in the past in order to emphasize his new religious ideals from those of the past.

Disease or no disease, the fact is that Akhenaten changed some important aspects of Egyptian culture that up until that point had remained largely unchanged for thousands of years. On top of that, later in his reign Akhenaten embarked on a project to erase references to Amun in temples throughout Egypt. The cult of Amun was a politically powerful organization in Egypt and it is doubtful that Akhenaten’s attempt to destroy the god’s images was a very popular move.

Now the answer to our initial question regarding the defacing of Nefertiti and her family should make more sense: It was a political statement made by someone who wasn’t a fan of the Amarna period trying to permanently erase Akhenaten’s attempts to change Egyptian culture by chipping away the Amarna-style art and Nefertiti’s etched cartouche.