By Jerry Offner, Associate Curator for Northern Mesoamerica

Houston Museum of Natural science

The Houston Museum of Natural Science and La Bibliothèque nationale de France have been cooperating in a new and unique scientific endeavor: special imaging of two Aztec Codex documents from before the Spanish conquest. Part one of this article will discuss the imaging techniques used to reveal new details of these very old and very rare documents and part two will discuss the fascinating (if slightly grisly) glimpses these codexes give into the Aztec judicial system.

The Aztec did not have a written language, but a complex system of symbols that could convey a variety of meanings at once: think emoji’s, but way more complex than that. It is a beautiful form of writing, most examples of which were destroyed during the colonial era. Thanks to projects like this one, modern scholars are able to expand their understanding of this ancient form of writing and learn a bit of history from the indigenous Mexican perspective. Documents like this, with their words resurrected from the past, open up a whole whole new world to researchers.

The meeting and research project

From March 20-23, 2017, the Bibliothèque nationale de France (the National Library of France, or BnF) worked together with The Houston Museum of Natural Science (HMNS) to acquire best in the world images of the most important documents in indigenous style from the Aztec “second city,” Texcoco, Mexico. This city, across the now mostly dry lake bed of Lake Texcoco to the east of Mexico City and the former Aztec capitol of Tenochtitlan, still exists today and has a history stretching back about 800 years.

Map of the Basin or Valley of Mexico in the 16th century. Contour lines and city locations have been adapted with permission from Jeffrey R. Parsons, Prehispanic Settlement Patterns in the Texcoco Region, Mexico (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology, 1971), 4.

Texcoco produced a multitude of historiographic and other manuscripts before the Spanish intrusion that began in 1519. Several manuscripts produced soon after contact remain among the most admired examples of historiography in the indigenous style. Historiography is concerned with the rules and practices of conveying historical information across generations, and the Texcocan methods have fascinating similarities to and differences from Western methods. This is only to be expected, as the New and Old Worlds were separated from each other by at least 15,000 years, and human beings in each world developed distinctive methods for solving human problems and concerns in all areas of their lives.

Investigators from six countries were involved in this four-day event:

• Dr. Fabien Pottier (Centre de Recherche sur la Conservation [CRC], Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris)

• Mr. Laurent Héricher (Chef du service des manuscrits orientaux, Département des Manuscrits, BnF, Paris),

• Mme. Ludivine Javelaux, Conservator (Institut national du Patrimoine, Paris)

• Mme. Paulina Muñoz del Campo, Restorer (Institut national du Patrimoine, Paris)

• Dr. hab. Gordon Whittaker (Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Germany)

• Dr. Amos Megged (University of Haifa, Israel)

• Dr. hab. Katarzyna Mikulska (Uniwersytet Warszawski, Poland)

• Ms. Betsy Haude (Senior Paper Conservator, Library of Congress, Washington, DC)

• Dr. Benjamin Johnson (University of Massachusetts, Boston, MA)

• Ms. Kate Peteet (University of Chicago, Chicago, IL)

• Ms. Hayley Woodward (Tulane University, New Orleans, LA)

• and Dr. Antonino Cosentino (Cultural Heritage Science Open Source, Catania, Italy), who somehow managed to take high quality images amid constant discussion and distraction).

During the first two days of the March meeting in Paris, we acquired images of four 16th century manuscripts using four technical methods VIS, UVF, UVR, IR. (See my earlier post for an explanation of these terms and how the images were taken– /2016/08/imaging-the-codex-xolotl-and-mapa-quinatzin/ ). We also took on an imaging challenge involving another complex and beautiful manuscript (the Aubin MS 20) from Oaxaca, Mexico, that was created before the arrival of the Spanish in 1519. We imaged the Codex Xolotl and the Mapa Quinatzin for the second time, and took first-time images of the Mapa Tlotzin, and the Códice en Cruz (manuscript in indigenous style in the shape of a cross).

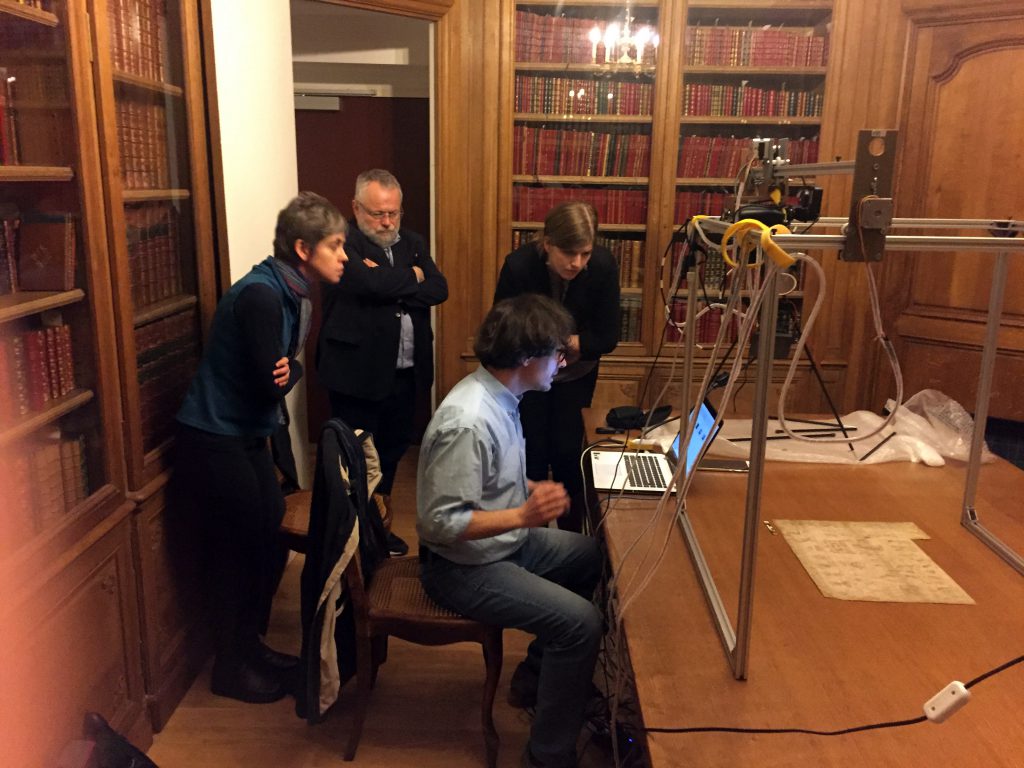

Figure 1a. Betsy Haude, Laurent Héricher and Hayley Woodward look on while Antonino Cosentino prepares the Archimedes scanner

Figure 1b. Jerry Offner works with Antonino Cosentino to image Mapa Quinatzin, leaf 3 (discussed later in this post).

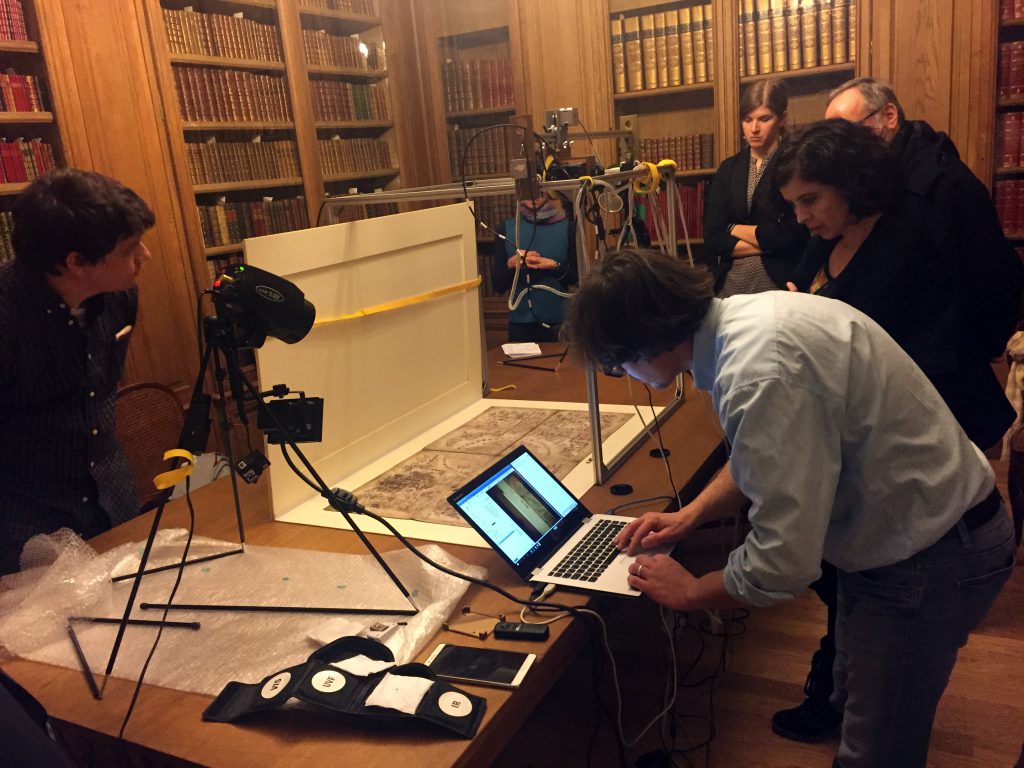

Figure 2a. Imaging the precontact manuscript called Aubin MS20, clockwise are Ben Johnson, Betsy Haude, Hayley Woodward, Gordon Whittaker, Katarzyna Mikulska and Antonino Cosentino.

Figure 2b. The all-important daily lunch! Loïc Vauzelle and Danièle Dehouve help the rest of us decipher the traditional chalkboard menu at a nearby restaurant.

The next two days featured presentations and joint investigation with the Codex Xolotl in the meeting room for consultation on the final day. Mme. Isabelle le Masne de Chermont, Directrice du Département des Manuscrits, Bibliothèque nationale de France, honored the gathering with an opening address, and most of the meeting participants gave presentations. Distinguished anthropologists such as Dr. Danièle Dehouve (EPHE, Paris) were in the audience and contributed valuable ideas. The Houston Museum of Natural Science (HMNS) contributed to the imaging costs as well as my travel expenses, and the BnF provided photography and meeting rooms along with extensive curatorial time (as a curator must always accompany any of these unique manuscripts). We hope that this kind of meeting will become a model for future meetings.

Figure 3a. Intense interest and activity as we try to understand the relationship between the three fragments of the Codex Xolotl and the reverse side of its first leaf. Clockwise, Kate Peteet, Gordon Whittaker, Benjamin Johnson, Hayley Woodward, Betsy Haude, Amos Megged and Katarzyna Mikulska.

Figure 3b. We show our appreciation by presenting a bottle of Dom Ruinart to curator Laurent Héricher, shown holding the Mapa Quinatzin.

Aztec ink, Spanish ink and UVF images

What discoveries did we make, and what did we learn during these four days? It was great to have a variety of experts from world-renowned institutions to enable new insights into both the basic physical nature of these documents and their attractive and engaging content. In this post, we’ll discuss how images taken in various spectral ranges will assist us in understanding some of the content of these beautiful manuscripts. In later posts, we’ll share some additional discoveries still in process.

The Aztecs used fine lines of an ink derived from carbon black to outline figures and record glyphs of people, places, offices and titles, and sometimes also concepts. In addition, they used carbon black in sophisticated notation systems to record dates in their calendrical systems and mathematical calculations in their vigesimal (base twenty) number system. Along with pigments made of vegetal, mineral, insect and perhaps other animal components, they created not just histories but also works of art on two types of native paper as well as on animal hide.

Early missionaries seized children of the Aztec elite and educated them in Western ways. Sadly, it became an accepted practice to write explanatory alphabetic texts, whether in Spanish or in the Aztec language, Nahuatl, on these works of art, and this defacement came to be expected and required if manuscripts in indigenous style were to be used in legal cases to defend indigenous rights to land and other resources.

The 16th century Spanish never came to learn, understand, or appreciate the image-intensive nonalphabetic indigenous manuscripts. Spanish religious leaders, fearful of the continuing and devoted use of such manuscripts by indigenous people, sought out and burned the great majority of them. They were also not above massive defacement of Aztec monumental art as when they ordered and carried out the destruction of the many reliefs and sculptures at the Texcocan site of Tetzcotzinco, which would otherwise be a World Heritage site today (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4. The Ruler’s Bath, a small part of the ruins at Tetzcotzinco, with Nezahualcoyotl’s outdoor throne of stone to the left, and remnants at the back of a large glyph of the city of Tenayuca, vandalized and destroyed by the 16th century Spanish. Photograph by Jerry Offner.

Figure 5. From his regal bath, Nezahualcoyotl was able see across the Valley of Mexico to Tenochtitlan and observe traffic in the lake system as well as on land. Modern skyscrapers in and near downtown, the former site of Tenochtitlan, can be seen amidst the midday haze (brackets added and contrast enhanced for background visibility on computer monitors). Photograph by Jerry Offner.

Returning to documents and their treatment by the Spanish and Spanish-educated Aztecs, the alphabetic texts that deface them can, in the end, describe only a small portion of the complex and intricately structured content of Aztec manuscripts—think of trying to describe a play or movie in all its detail and nuance using just alphabetic text. Therefore, the Spanish or Nahuatl alphabetic texts they wrote (called “glosses”) contain only small parts of the original information in the Aztec graphic communication system.

Unfortunately, the Spanish ink–“iron gall ink” made from iron salts and vegetal-source tannic acids–was not as kind to paper, whether indigenous or European, as Aztec ink. Iron gall ink glosses often damaged indigenous manuscripts. It does have one virtue, however: it shows up very strongly in UVF images. In this post, we’ll describe one such example that helps us to understand the Aztec legal system better.

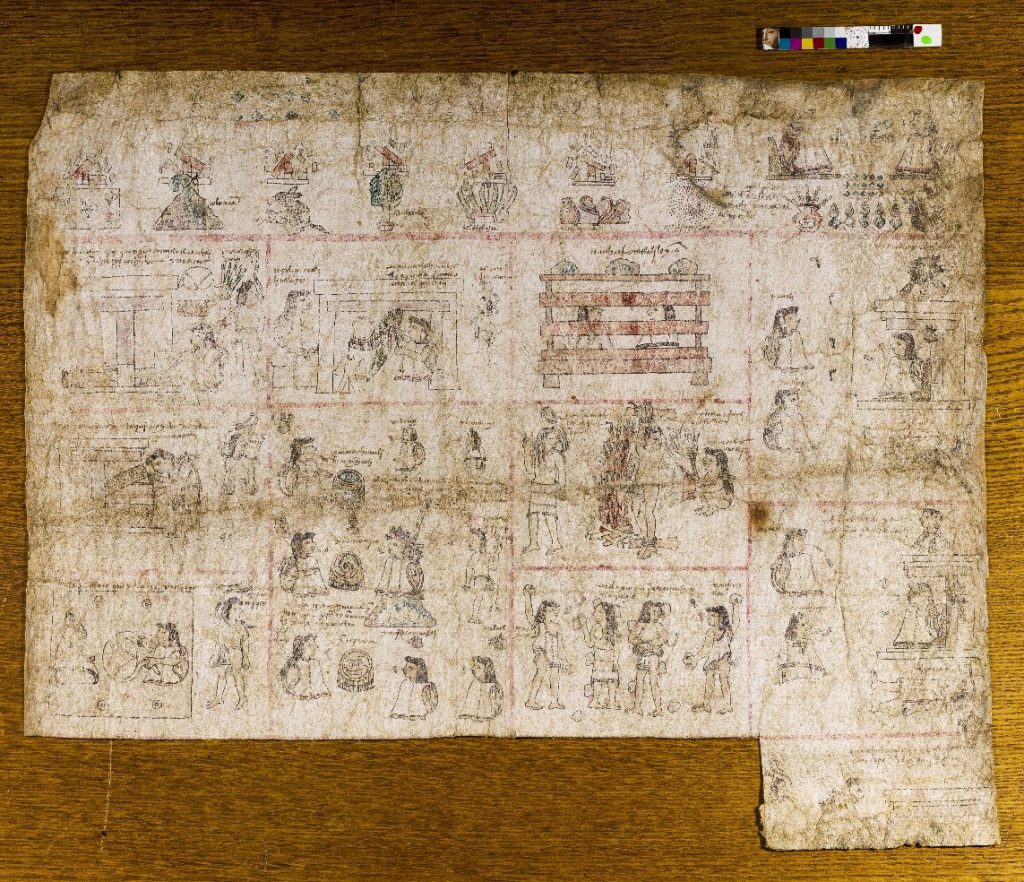

The Aztecs had sophisticated legal systems and schools of jurisprudential thought that varied from city to city, but shared many features. I first wrote about these, especially those in Texcoco, in the early 1980s and recently wrote an article on Aztec law from my perspective of thirty years later. The Aztec had a “legalistic” legal system—that is, in criminal law, specific punishments were rigorously applied if certain facts were established in a legal case. We can see some few of their legal rules memorialized in the third leaf of the Mapa Quinatzin. Nevertheless, no set of legal rules can hope to define all that can happen among human beings, so precedent arising from case law also played a part in their system and we can see precedent-setting legal cases on this manuscript also.

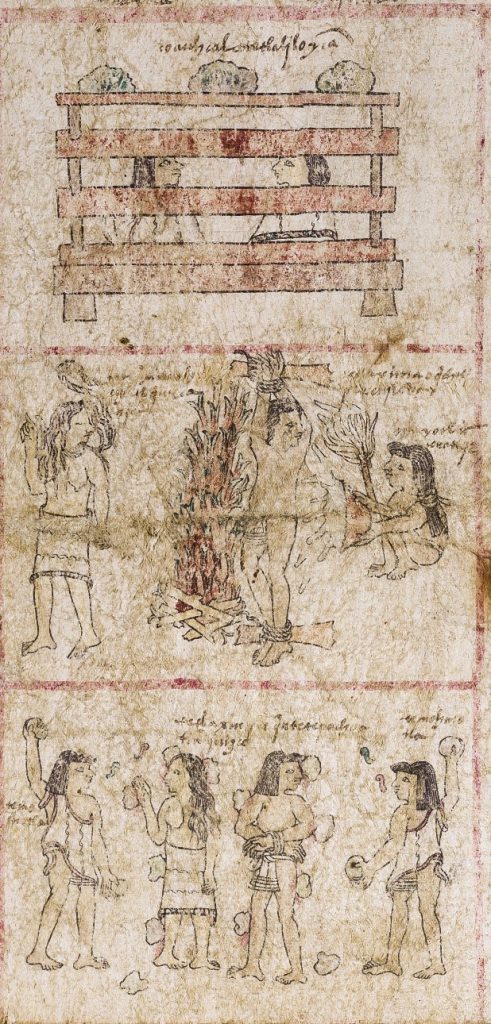

Figure 6. The third leaf of the Mapa Quinatzin, in VIS (visible) light. At the top is a horizontal area containing seven conquests and other historical data. Below it are four columns depicting legal rules and cases. All glosses on this manuscript are in the Aztec language, Nahuatl. Image by Antonino Cosentino of CHSOS, courtesy Jerry Offner, HMNS and BnF.

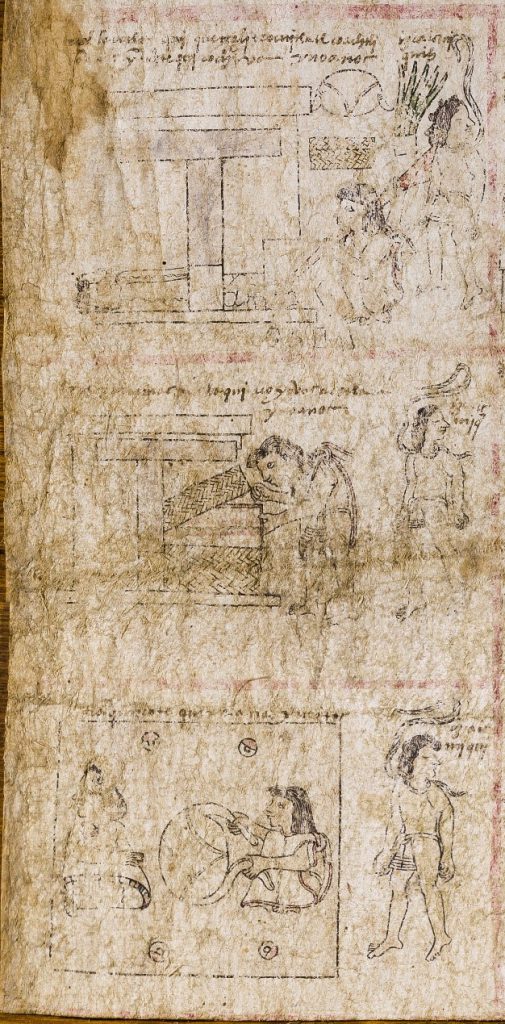

The third leaf of the Mapa Quinatzin is composed of several columns. We need to keep in mind that the bottom of the leaf has been cut off, so we do not know how extensive the listing of legal rules might have been on this and possibly following leaves. The first column (Figure 7) shows the circumstances involving theft that led to death by garroting. In the top row, a burglar digs into the wall of a house to steal a variety of valuables. The second row depicts a more casual theft from a family’s container of important and precious goods, while the third row shows the theft of an inattentive merchant woman’s bundle of goods in the marketplace at night.

Figure 7. Mapa Quinatzin, leaf 3, column 1

Figure 8. Mapa Quinatzin, leaf 3, column 2 Image by Antonino Cosentino of CHSOS, Image by Antonino Cosentino of CHSOS, courtesy Jerry Offner, HMNS and BnF. courtesy Jerry Offner, HMNS and BnF.

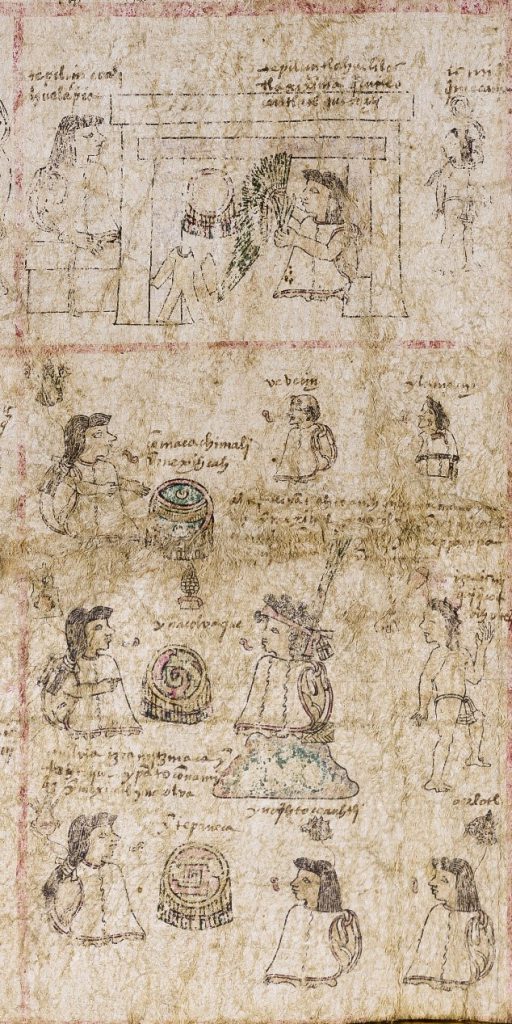

The second column (Figure 8) deals with nobles who have failed in their duties, either by neglecting their property and war costume, or by failing to subordinate to the ruler, even after the ruler and his two allied states explicitly and successively threaten war to his warriors, his elders, and to the ruler himself.

The third column (Figure 9) shows the process and punishments for adultery, beginning with the imprisonment of the adulterous couple in a wooden cage secured by stones at the top.

Figure 9. Mapa Quinatzin, leaf 3, column 3

Figure 10. Mapa Quinatzin, leaf 3, column 4 Image by Antonino Cosentino of CHSOS, Image by Antonino Cosentino of CHSOS, courtesy Jerry Offner, HMNS and BnF. courtesy Jerry Offner, HMNS and BnF.

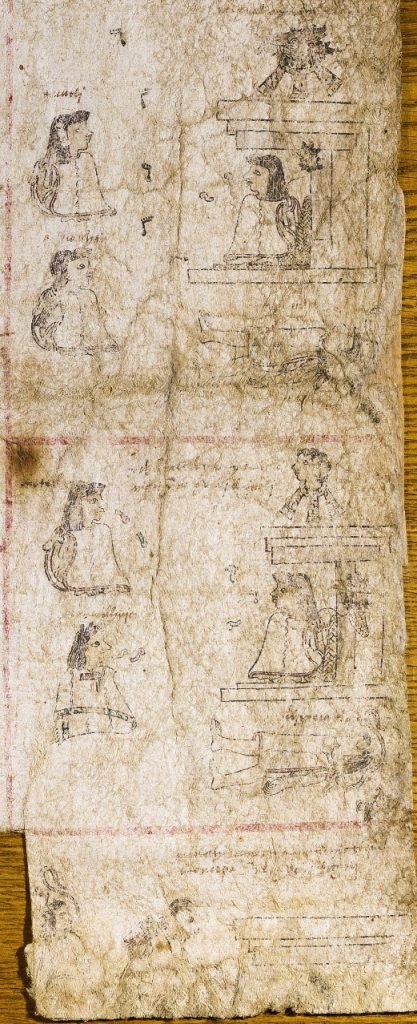

The fourth column (Figure 10) deals with specific legal cases of judicial corruption in the time of the two most famous rulers of Texcoco, Nezahualcoyotl (1431-1472) and his son, Nezahualpilli (1472-1515). The details of the first case, in the time of Nezahualcoyotl, whose glyph is seen on top of the court building, are not well known. A judge named Cuauhtli (Eagle) seated in a court building speaks to a “tecutli” (a lord of uncertain rank, perhaps a fellow judge), and an “achcauhtli” (literally “older brother,” a title for an official with duties similar to a bailiff). He is then shown leaving the court by a trail of his footprints and is depicted punished by garroting for this behavior. We do know that legal proceedings were to be held in the presence of other court officials, so the judge’s punishment may have been related to his leaving the court or leaving the court to proceed with the case elsewhere. The second case, in the time of Nezahualpilli, whose glyph appears on top of the court building, involves a corrupt judge, Cen Cuauhtzin or One Eagle, who held court in his own house (“ychan…” “at home, in his house…” can be seen at the beginning of the gloss) instead of in the proper government court. He was executed for this behavior.

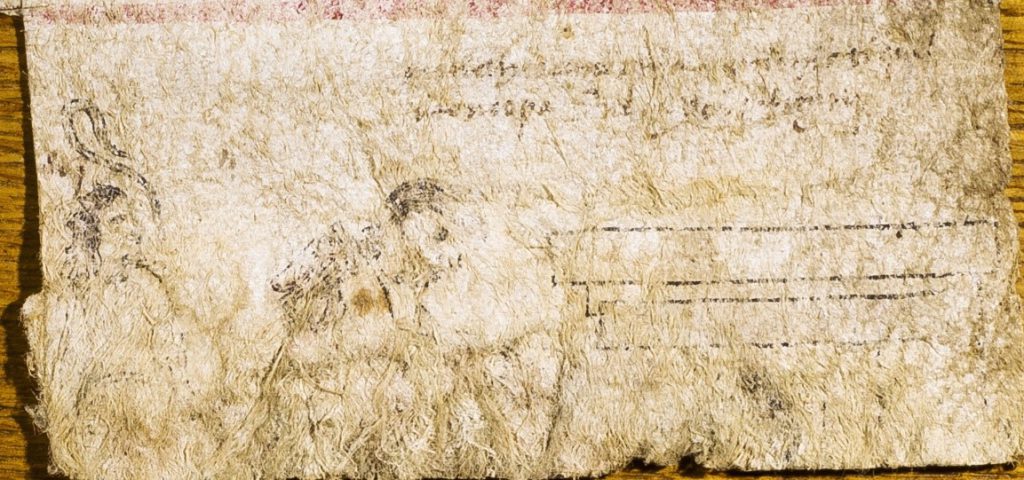

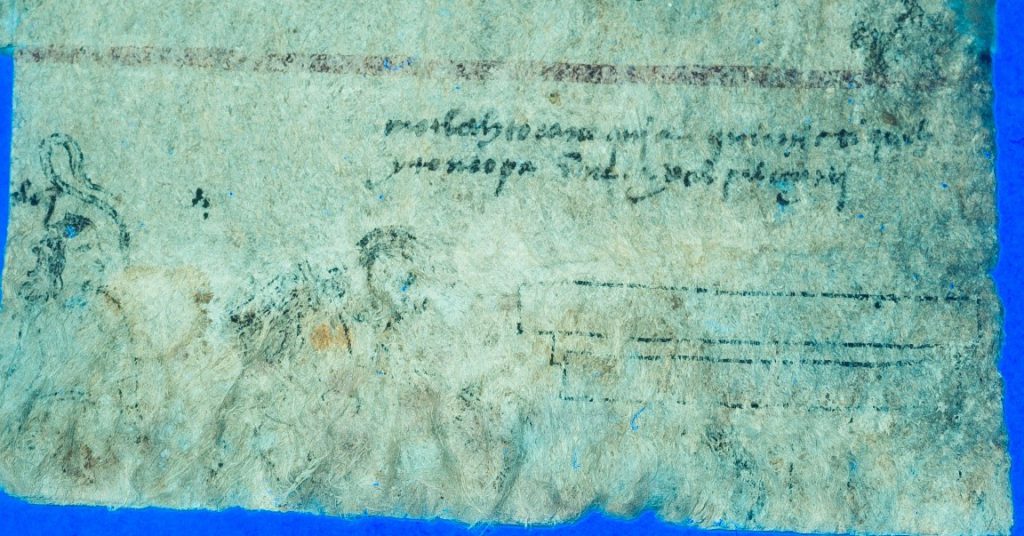

The third case has remained a near total mystery because a portion of it containing the illustration of the offense was cut off, probably by the late 16th or early 17th century. Two lines of text written in Nahuatl (Figures 11 and 12) seemed to be the only hope of understanding more of the content of this case. The second lines, barely visible, was nevertheless easily understood:

“ytencopa y^ neçavalpilçintlj”

(itencopa in Nezahualpiltzin—“tzin” is an honorific suffix added to the ruler’s name).

Figure 11. Mapa Quinatzin, leaf 3, column 4. Row 3, VIS, from 2017. Image by Antonino Cosentino of CHSOS, courtesy Jerry Offner, HMNS and BnF.

Figure 12. Mapa Quinatzin, leaf 3, column 4. Row 3, close-up UVF, from 2016. Image by Antonino Cosentino of CHSOS, courtesy Jerry Offner, HMNS and BnF.

This means “by order of Nezahualpilli.” That left the first line as the remaining source of information and I called in help from two Nahuatl experts, Gordon Whittaker (listed above) and Julia Madajczak of the Uniwersytet Warszawski (University of Warsaw) and provided them with the UVF image. Gordon replied first and Julia soon confirmed that the correct reading was:

motlahtocanequja quimictiqueh

“he pretended to be king; they killed him”

The first two legal vignettes involve a judge seated in court, while to the left, certain important figures and events are depicted that describe the offense. In this vignette, we can make out a man presenting himself, apparently quite aggressively, before the court with an executed man in the background. The executed man appears not to be a judge. He was executed with disheveled hair and wearing only a loincloth, like the ordinary criminals in the other columns. The executed judges in the fourth column are given special treatment: they retain their cloaks and their hair is undisturbed. This information, taken together with the gloss, indicate that the judge is being accused of exceeding his authority by ordering an execution without the usual judicial review. Probably the judge was depicted as executed in the area now cut off, with his cloak on and his hair undisturbed. In sum, then, reading the gloss in Nahuatl helps understand the content better but it is not a full substitute for the Aztec scene that has been damaged.

There remains a good chance that we will be able to understand all three cases in the column with additional investigation of the enhanced images. Because all the scenes on Mapa Quinatzin, leaf 3 are related as a fragment of Texcocan jurisprudential thought, knowing a little more about one scene enhances our understanding of their entire judicial process and jurisprudential thought.

In future posts, I’ll describe some of the other discoveries we made from the images recently acquired, including the precontact manuscript Aubin MS 20. The last good edition of the Codex Xolotl was written and produced in 1951. Already, we are planning a new edition utilizing the latest technology, based on this unique March, 2017 meeting funded in part by the Houston Museum of Natural Science and hosted by the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Figure 13. The meeting ends at the Rue Richelieu entrance to the BnF, March 23, 2017.

Jerry Offner