So snails suck, right? They’re boring and slow and they don’t do anything cool. Some of them make pretty shells that you find on the beach, but they’re pretty much slimy and gross and basically not interesting at all.

Said no one ever. At least not those who understand the world and daily life of snails. They’re tough, vicious, and sometimes terrifying in their adaptations to help them feed and protect themselves, especially in the case of marine snails, which can be as varied in shape, size, and color as the imagination.

“There are about 30,000 known species of snail,” said Gary Kidder, HMNS Discovery Guide and snail expert. “They’re a ‘Walt Disney’ class: if you can dream it, they can do it.”

Known in the science community as gastropods, meaning literally “stomach foot,” snails feed using a rasp-like tongue called a radula. Like most animals, the teeth vary from species to species based on what particular type of food the snail eats. In carnivorous snails, these teeth are like fish hooks that tear the flesh from their prey. Imagine having your skin licked off by a giant cat’s tongue! Terrible.

Snails are not always small; they can grow to be massive. The Australian trumpet, or Syrinx aruanus, produces shells that can be as big around as your thigh. Measuring more than 30 inches in length, the record-holder for biggest snail shell in the world is on display in the Strake Hall of Malacology at the Houston Museum of Natural Science. It looks like you could fit a football inside this bad boy.

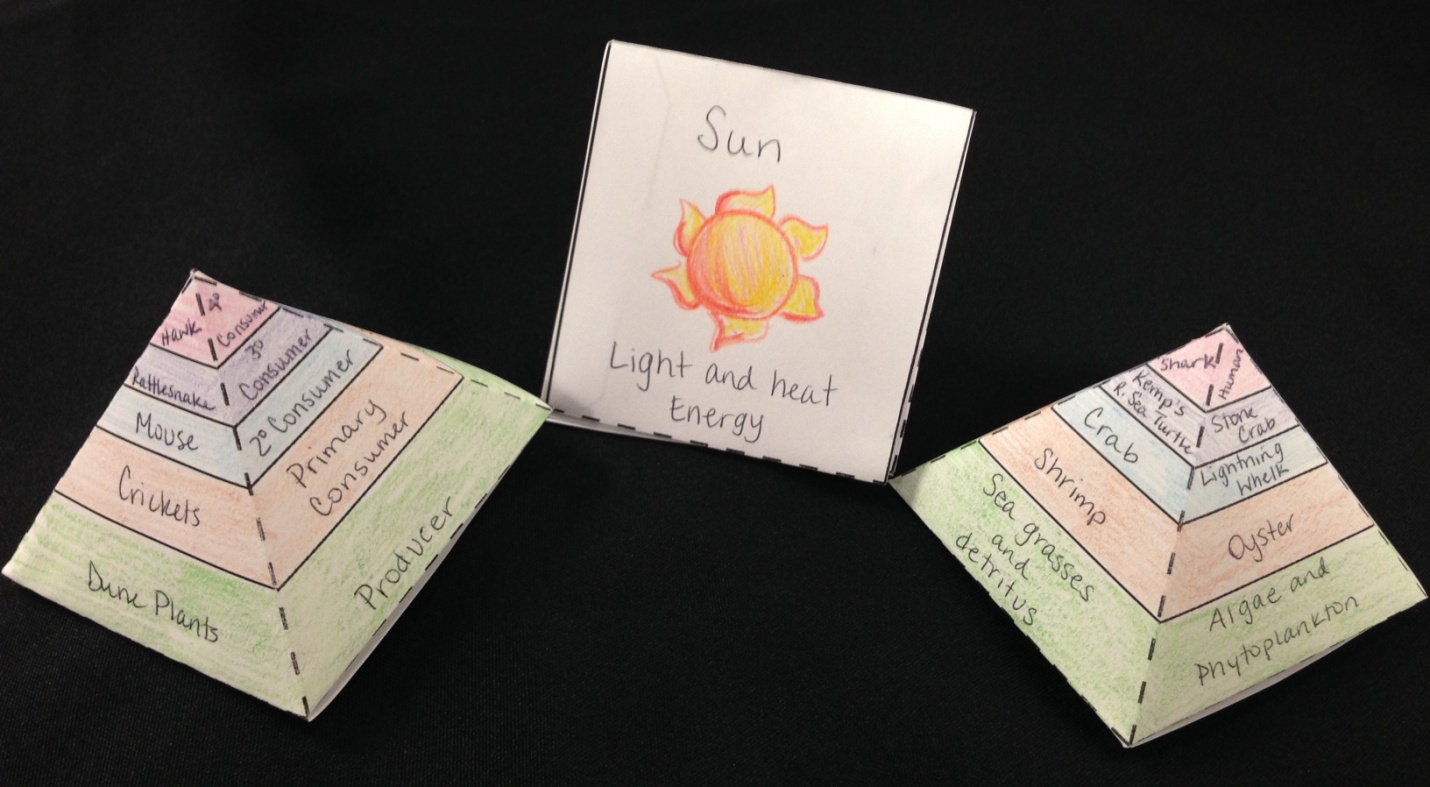

Lightning whelk. Credit: DixieHwy

Predatory snails use some barbaric tactics to kill and eat their prey. There’s no saving a bivalve caught by a lightning whelk, Busycon perversum (incidentally, the state shell of Texas). The lightning whelks pries open clams, wedging its soft foot between the halves of its shell, then it uses its radula to scrape out the clam a piece at a time. Kind of like a stranger kicking down your door and coming into your house to get you. Frightening.

That’s just the beginning. The moon snail, in the family Naticidae, bores into the shells of mollusks and crabs with its radula and an acid secretion. That’s right: acid. It melts a tiny hole through its prey and licks out its insides with its tongue. No thank you!

Moon snail. Credit: Chris Wilson

To stun or kill their prey, many marine snails use some of the strongest venoms on Earth. The teeth in the radula of the geography cone, or Conus geographus, are modified to carry a venomous sting that disrupts insulin in its victims. Like a revolver loaded with up to twenty hypodermic needles (instead of six bullets), the cone snail harpoons its prey, sometimes with several stings in a matter of seconds.

“The venom gives you diabetes, basically,” Kidder said. “It makes you loopy. And if they’re able to hurt something our size, a fish, it’s usual prey, isn’t going to be an issue for it.”

Conus geographus. Credit: Patrick Randall

The harpoon of the C. geographus can penetrate human skin and sometimes gloves and wetsuits depending on its size. A single sting from a Conus snail can cause muscle paralysis, difficulty breathing, and death. No antivenin exists; victims must be hospitalized until the venom wears off. Don’t pick these suckers up unless you’ve got comprehensive health insurance!

Scientists, however, see the cone snail’s venom as an opportunity for medicines, and are working to synthesize compounds from its unique chemical cocktail as treatments for a variety of diseases.

Carrier snail. Credit: James St. John

Conus isn’t the only gastropod with potential benefit to humanity. The carrier shell, in the family Xenophoridae, Greek for “bearing foreigner,” uses a type of “concrete” to attach foreign objects to itself, reinforcing its own shell as it grows. The snail’s building media include other shells, pebbles, small pieces of coral, and in some instances human refuse like bottle caps. Scientists have even discovered new species from the shells attached to Xenophora.

“This is an aquatic saltwater snail that makes a cement that ‘dries’ underwater,” Kidder said. “If we can figure out how it does that, the economic possibilities are wild!”

So next time you see a land snail leaving a trail of slime, or a shell on the beach that once belonged to a marine gastropod, remember that in its own world, this slimy, slow-moving creature is a rock star.