Quick: What do Texas and France have in common?

Actually, I should rephrase that: Who do Texas and France have in common?

The answer? Dr. Jean Clottes, a leading French prehistorian.

It makes sense that a Frenchmen would love his country, but what is Dr. Clottes looking for in Texas? It turns out the answer is down to earth: rock art. In Dr. Clottes’ opinion, Texas rock art ranks right up there with rock art in La Douce France.

Anyone interested in rock art is most likely familiar with the famous painted prehistoric caves in France and Spain. Sites like Altamira and Lascaux are household names in the world of art history. Dr. Clottes has been heavily involved and invested in the study and preservation of Lascaux Cave. We were very lucky to have him as a speaker at the museum recently. He elaborated on cave art in general, and Cosquer cave in particular. Earlier in the day, he took a group of art history students from the University of Houston through an exhibit on Lascaux cave, currently at the Museum. He regaled us with stories about his own work at the cave. He patiently addressed recent newspaper reports of “another Lascaux” that allegedly exists near the original Lascaux cave.

What brought him to Texas, though, was rock art — to be more precise, rock art from the Lower Pecos. This art has been studied extensively, among others, by the Archaeological Institute of America, the Rock Art Foundation, SHUMLA and, of course Dr. Clottes and his Texas colleagues.

On Feb. 7 and 8, HMNS organized a trip to the Lower Pecos area to see this wonderful rock art. SHUMLA staff members Andrew Freeman, Jeremy Freeman, and Vicky Munoz led a group of 25 people to see two sites: White Shaman and Painted Shelter.

Even though we were on the Texas-Mexico border, there was a thin coating of frost on the windows of our van. As the day progressed, however, we enjoyed a beautiful blue sky with plenty of sunlight.

Our first stop was Seminole Canyon State Park, located 9 miles west of Comstock on U.S. Hwy. 90, just east of the Pecos River bridge. In North America, this is an area with a long history of human presence. The park’s website informs us that:

“Early man first visited this area 12,000 years ago, a time when now-extinct species of elephant, camel, bison, and horse roamed the landscape. The climate at that time was more moderate than today and supported a more lush vegetation that included pine, juniper, and oak woodlands in the canyons, with luxuriant grasslands on the uplands. These early people developed a hunting culture based upon large mammals, such as the mammoth and bison. No known evidence exists that these first inhabitants produced any rock paintings.”

Over time, climatic conditions changed, and humans had to adapt. Some 7,000 years ago, the landscape looked much like today.

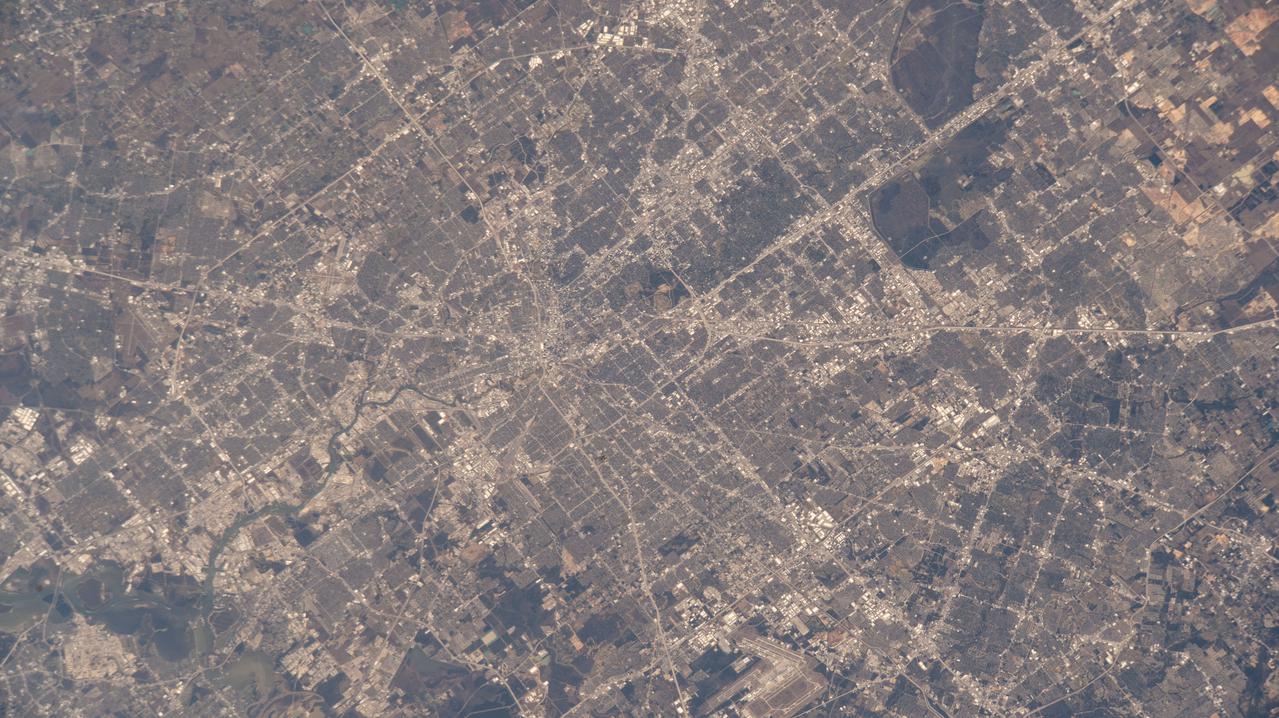

Landscape looking toward the Pecos River with modern bridge crossing. With the exception of the bridge, this is what early Texans would have seen as well.

There is a reason why archaeologists and art historians are drawn to this area. One can find more than 200 pictograph sites here; they contain rock paintings ranging from single images to caves containing panels of art hundreds of feet long.

This is where we visited the White Shaman site. This is a rock shelter, rather than a cave. It contains a pictographic panel measuring four by eight meters (about 13 by 26 feet). The panel depicts more than 30 anthropomorphic (human-shaped) figures. Some of these are impaled, some are even shown as skeletons. We also saw zoomorphs (animal-shaped figures): red deer, all impaled. Finally, our guides pointed out images that defy interpretation, such as more than 100 dots, occurring all over the panel. A serpent-like figure divides the panel in two. Crenelated lines are present as well.

The name of the rock shelter, White Shaman, is derived from the white figure appearing in the center of the panel.

This rock art, commonly dated back to the Middle Archaic, about 4,000 years ago, is among the oldest known in North America.

After a delicious barbecue lunch, we went on to visit a second rock art site — this one on private property. After a bumpy ride, we got to see Painted Shelter.

Known since at least 1937, the art here shows human figures (including one with a bow), as well as animals (deer-like figures, a bird, and a catfish).

This is Painted Shelter, showing representations of deer-like animals as well as two human figures, one of whom is holding a bow.

The Pecos River rock art has been studied for many years. As early as 1849, Captain C. French reported on Indian paintings he saw near the mouth of the Pecos River. In the 1930s, a systematic effort to record and study Pecos Rock Art started. These efforts continued into the 1950s. The construction of Lake Amistad spurred on further research in the 1960s.

The role of museums in the scientific study of ancient Texas, and subsequent dissemination of scholarly knowledge, should not be underestimated here either. In the early 1980s, the Witte Museum in San Antonio brought together archaeologists, paleobotanists, art historians, and anthropologists to investigate the lifestyle of the ancient inhabitants of the Lower Pecos region. Rice University started their Pecos Project around the same time, drawing on different fields of study to help decipher Pecos art. By the late 1980s, it was possible to date rock art using AMS technology, an advanced form of radiocarbon dating.

Recently, one person has been in the forefront of Pecos Rock Art research: Dr. Carolyn Boyd. Since her graduate student days in the 1990s, she has spent most of her career exploring and studying rock art. Author of Rock Art of the Lower Pecos, Dr. Boyd is currently working on a new publication. On Feb. 25, she will give a lecture on her latest research at HMNS. For more information, click here.

Until Mar. 23, you can also come see our exhibit Scenes from the Stone Age: The Cave Paintings of Lascaux. If you are interested in early expressions of art from both the Old and New World, make sure you catch both events.