Our moon goes by many different names depending on the season and its position relative to the Earth. The evening of Sunday, Sept. 27, it will become three identities at once, an exceptionally rare occurrence. For the first time in 33 years, Earth will witness a total eclipse of the moon at its perigee near the autumnal equinox: a blood moon, a supermoon and a harvest moon combined. You can watch the eclipse of historic proportions anywhere on the planet where the moon is visible, but at the George Observatory, you can learn about eclipses while you catch it in action.

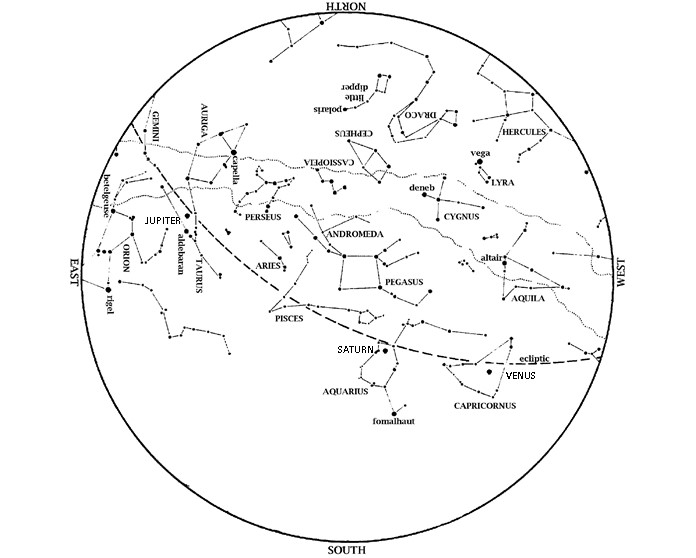

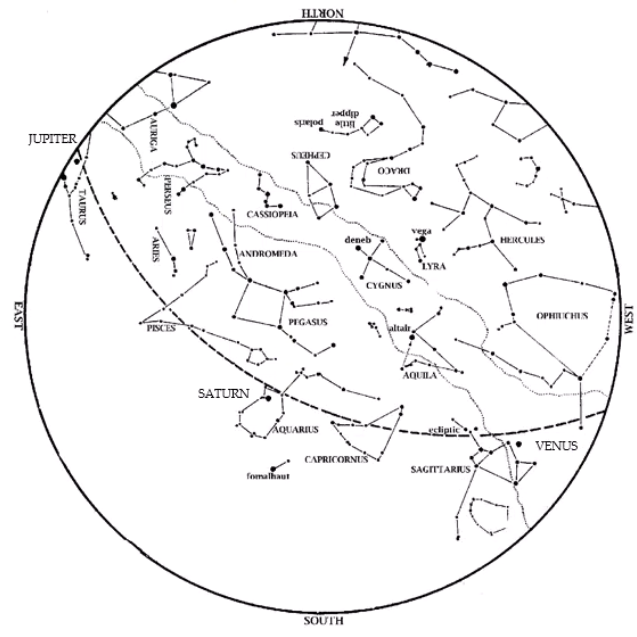

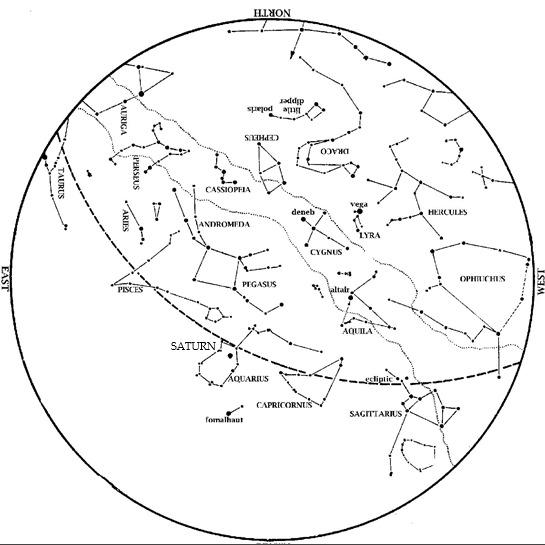

Houstonians will be able to see the whole event, which begins right as twilight ends. Lunar eclipses occur when the full moon moves into the Earth’s shadow. The first part of the Earth’s shadow the moon will encounter is called the penumbra. For our area, sharp-eyed observers will notice only a slight dimming of the moon between 7:10 p.m. and 8:07 p.m. Central Daylight Time (CDT). The moon moves into the darkest part of the Earth’s shadow, the umbra, at 8:07 p.m., and will be totally eclipsed by 9:10 p.m. Totality will last until 10:24 p.m. The moon will then exit the umbra and leave it completely by 11:27 p.m., when the eclipse ends.

This diagram displays the movement of the moon through Earth’s shadow during the total eclipse. Times are shown in Eastern Daylight Time (EDT). For times in CDT, our time zone, subtract an hour.

The moon’s brightness during a total eclipse depends on the amount of dust particles in the atmosphere. A large amount of dust from a volcanic eruption, for example, can make the totally eclipsed moon almost invisible. With little dust in our atmosphere, the moon glows reddish-orange during totality. This is because only the sun’s red light comes through the Earth’s atmosphere and falls on the moon even while it is in the Earth’s shadow. As the diagram shows, the moon passes through the southern part of the shadow, for 74 minutes of totality. As a result, the northern limb, closer to the center of Earth’s shadow, will appear darker.

Sunlight refracted through Earth’s atmosphere gives the moon its red color during a total lunar eclipse, also called a blood moon by many. This is the same red light you see at sunrise and sunset, but from the moon’s perspective. If you were standing on the moon during the eclipse, you would see a dark Earth ringed in a glowing halo of red.

You may have heard that this is a “supermoon eclipse.” That’s because this full moon happens less than one hour after the moon makes its closest approach to the Earth, called perigee. What’s more, this is the closest perigee of the year, 145 km closer than on Feb. 19. At perigee, the moon is the biggest it can get in our sky, though the difference is only slight. Your pinky held at arm’s length still covers it up!

A supermoon eclipse is a rare phenomenon. The last one occurred in 1982, and there have been only five since 1900. After Sunday, the next one will occur in 2033. Compare this to a blue moon, or two full moons occurring in a month. The last blue moon occurred this year on July 31, and prior to that, on Sept. 30, 2012. Perhaps we should revise the phrase “once in a blue moon” to “once in a red supermoon.”

We can also call this a harvest moon since it’s the full moon closest to the fall equinox. Because the moon rises close to sunset for several days before and after the night of the full moon, its light allows harvesters to keep working instead of stopping at sundown. The fall equinox occurred Wednesday, Sept. 23, so this full moon is indeed the harvest moon, which makes this Sunday’s event a “harvest moon eclipse.”

Our own George Observatory will be open Sunday night from 6 p.m. to midnight specifically for observing the eclipse. Here at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, our Starry Night Express shows in the planetarium will feature the eclipse. We’ll also give a preview of the event before every planetarium show that weekend. If you can’t join us here or at the George, just remember that whoever can see the moon can see the eclipse. You can therefore watch the eclipse from your front or back yard, or even out the window if it faces the right angle! Only overcast skies can stop you from seeing the eclipse. Let’s hope our current trend of clear skies holds through Sunday.

This is the last of four lunar eclipses last year and this year, all total, and all visible from North America. That series ends here; in Houston, we’ll see our next total lunar eclipse at dawn Jan. 31, 2018.